“I have receiv’d by the hands of mr Fleming”: Thomas Smith, the Fleming Family and St Edmund Hall

22 May 2024|James Howarth

- Library, Arts & Archives

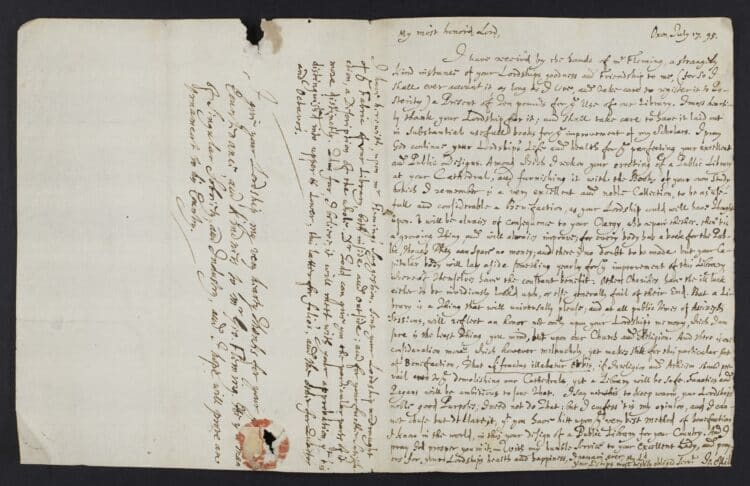

On 17 July 1695, Principal John Mill wrote to Thomas Smith, Bishop of Carlisle, to thank him for the gift of £10 to buy books for the Hall Library.

Previously we looked at the books that were bought with the money, what an included set of drawings and plans of the Old Library revealed about how it looked in 1695 compared to today, and also what Mill’s letter revealed about his conception of the role of libraries.

However, the letter also throws light on the circumstances that led to Smith’s donation and its connection to the early career of one of the Hall’s most distinguished alumni.

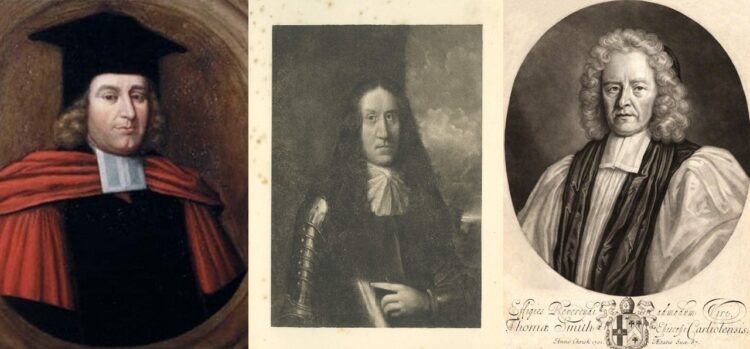

In the opening line of Mill’s letter we learn the spur for Smith’s generous donation: he writes that the gift has been “reciv’d by the hands of mr Fleming.” This is Sir Daniel Fleming (1631–1701) of Rydal Hall, a prominent member of the Westmoreland gentry, an antiquarian, sometime MP and Sheriff of Cumberland. Fleming, like Mill and Smith, had been a student at Queen’s (the college was founded for the education of scholars from Cumbria and Westmoreland) and four of his eleven sons studied in Oxford, three also at Queen’s but one, his fourth son George (mat. 1688), studied at the Hall and was still in residence in July 1695.

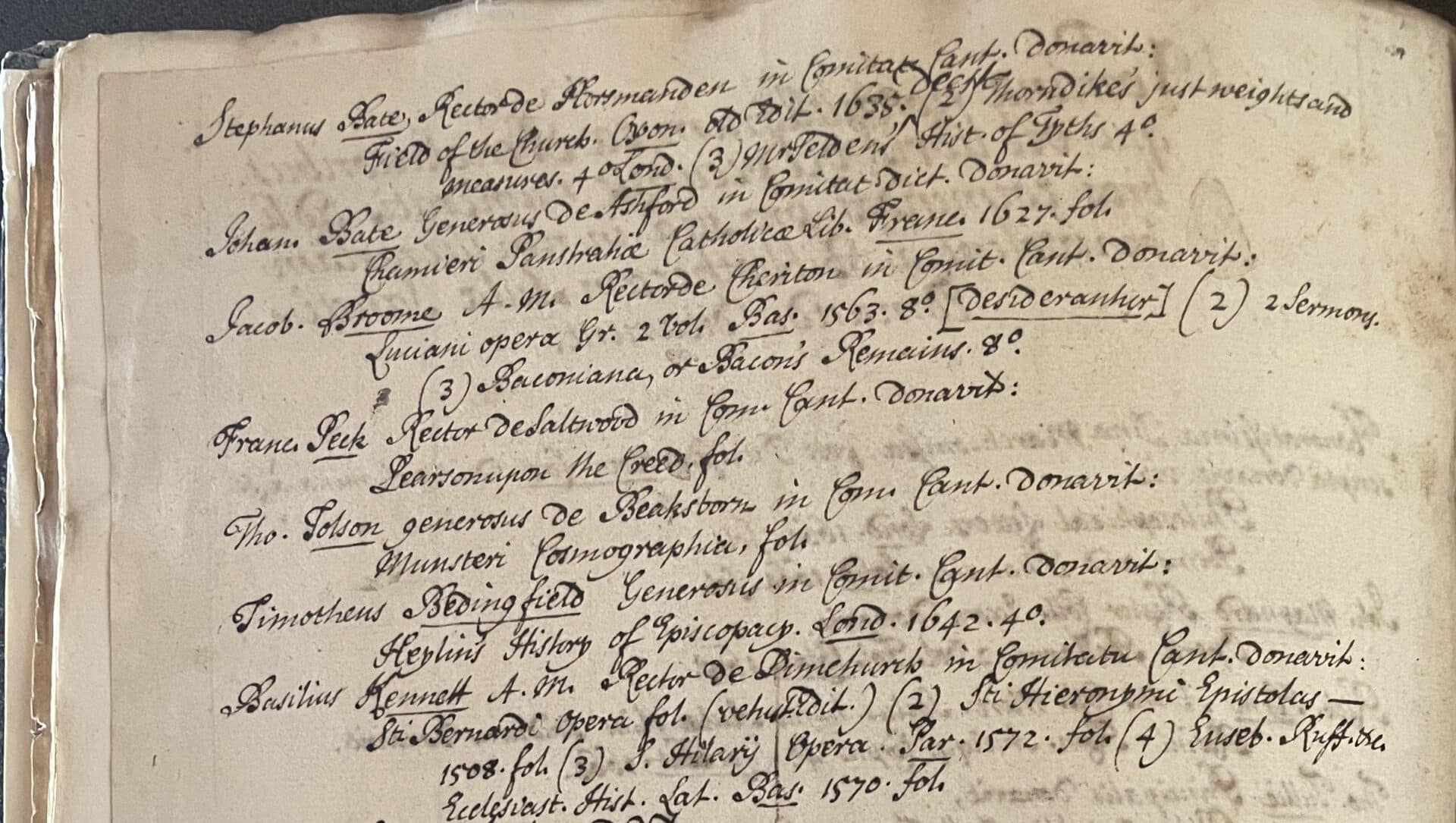

This is not the only case of the parent of a Hall student apparently encouraging donations to the Library in this period. A list of Library donors compiled by Thomas Hearne (mat. 1695) shows not only the gift of four books by Basil Kennett, Rector of Dimchurch in Kent and father of Aularians White (mat. 1678) and Basil (mat. 1689), but also a further nine books given by Dimchurch’s local squire and the incumbents of neighbouring parishes, none of whom had any other connection to the Hall.

Thomas Smith was a close connection of Daniel Fleming; he had been his tutor at Queen’s and was the second husband of Fleming’s mother-in-law. He was also George’s Godfather, had ordained him at Rose Castle (the palace of the Bishop of Carlisle) in June 1694, and made him the Vicar of the parish of Aspatria in March 1695. So, Smith’s interest in the Hall is more clearly explained.

Daniel Fleming was a prolific correspondent – more than 6,000 letters from him to various friends and connections as well as copies of his own letters survive. Between 1904 and 1924, John Magrath, then Provost of Queen’s, edited a selection of those relating to Fleming’s and his sons’ education in three volumes as The Flemings in Oxford. Using the published letters, we can reconstruct the likely sequence of events around Smith’s donation.

On 7 March 1695, George Fleming took his MA at Oxford and shortly afterwards departed for Cumbria. A letter written around the 9 March to Daniel Fleming by Henry Brougham, a Queen’s Fellow who was Tutor to Fleming’s younger sons Roger and James and also a distant cousin, says that “Cous: George brings down with him ye weight of his new degree, as deep as ye roads are” (the winter of 1694–1695 was particularly bitter) and another written by James Fleming on 11 March clearly expects George to be at home by the time it is received at Rydal.

On 26 March, George was collated and inducted into his parish at Aspatria by Bishop Smith. He remained in the North for the next several months; a further letter from James on 15 May implies that George is still in Cumbria. He appears to have been exercising his new responsibilities: a letter written by Fleming to Mill in June says he “since his coming into ye Country hath been Collated, Instituted & Inducted into ye Vicarage of Aspatrick ; & who hath preached divers good Sermons with great applaus.”

George returned to Oxford, where he had permission from the Bishop to pursue advanced theological study under Mill’s direction, by early June. He is imminently expected in a letter written by Roger Fleming to his Father on 8 June. His return to study in Oxford appears to have been the immediate occasion of Smith’s gift to the Hall Library.

Fleming’s letters and money sent to his sons were carried by a bearer named Thomas Burnyate who made regular trips from Kendal to Oxford, so the correspondence advances in batches as the Oxford recipients all respond at the same time. On 20–21 June 1695, Daniel wrote to his three sons, Henry Brougham and Mill as well as despatching £5 to George and £25 to clear the considerable debts that Roger and James had incurred. It is almost certainly at this point that the £10 of Thomas Smith was also sent “by the hands of mr Fleming” although it is not mentioned in the published correspondence – Fleming’s own letter to Mill focussed on his son. There must have been a further covering note from Fleming, as Mill says to Smith his inclusion of a description of the Old Library was “…upon mr Fleming’s Suggestion.”

This packet of mail reached Oxford around 16 July as can be seen from the fact that George, James and Henry Brougham respond immediately. Mill too wrote back at this point (as can be seen from an acknowledgement in Fleming’s next letter to him in October) but his letter again is not in Magrath’s work and may not have survived.

Mill’s letter to Smith is dated 17 July so his thanks for the gift were sent with a commendable promptness, something I can only acknowledge I should try to better emulate in my thanks to today’s generous donors to the Library!

If Mill wrote back with such alacrity it does raise the question of when the drawings of the Library were prepared as there would not have been time for them to be specially commissioned. Perhaps they survived from the planning and construction of building in 1680–1685? The only other records of the construction are payments for various parts of the project recorded in the New Ledger Book. Perhaps multiple copies of the drawings had been made to distribute to patrons?

“He is a man of Singular Sobriety and Industry”: George Fleming in 1695

Although George Fleming’s ecclesiastical and academic career seemed to be flourishing in 1695, the same could not be said of his brothers Roger and James at Queen’s. Their academic work was poor, they had fallen among a fast set and were rapidly running up debts. Indeed, in the packet of letters sent by Daniel Fleming on 21 June, the one to Roger recalled him home at once on the same horse that George had used to travel to Oxford (Roger had in fact already left of his own accord, although a protracted six-month stay with cousins meant he didn’t reach home until the next year). James’ study at Queen’s staggered on for a year before he too left under a cloud, despite a last-minute scheme to transfer him to the more sober environs of Teddy Hall.

The chance that had enrolled George at the Hall rather than its neighbour seemed fortuitous: he had arrived with letters of introduction to both the Provost of Queen’s and the Principal of St Edmund Hall – the Provost was away from the city so George matriculated at the Hall. On the surface the portrait painted of George Fleming by the letters of his father, his brothers’ tutor Henry Brougham and Mill is deeply flattering.

“He is a man of Singular Sobriety and Industry, and I hope will prove an Ornament to his Country”, writes Mill to Thomas Smith in his final hasty postscript, perhaps realising at the last minute he should praise the Bishop’s godson and protégé.

“Be advised, in all things, by…Brother George, who hath got some Preferment, & a very good Report, by his civility, sobriety, & Studiousness”, James Fleming is advised by his Father. “I wish his Brothers would follow so good an example of Studiousness and frugality”, concurs Henry Brougham.

In this context it is easy to see Smith’s gift to the Hall as a reward for a ‘job well done’. However, there may also be a slightly different subtext to the gift – a subtle reminder to Principal Mill that his pupil now had obligations to his parish and his Bishop.

“Have a care of loseing ye Substance in catching at ye Shadow”: the discontents of George Fleming

The need for George to finish his studies and return to Cumbria becomes a persistent theme from this point in Fleming’s correspondence with his son and Mill. In October 1695 he wrote to the Principal: “While he shall stay with you, I doubt not, you’l be adviseing him to be fitting himselfe for ye Ministry; that he may ye better discharge his Duty at Aspatrick, when as he shall be there. How long ye Bishop will give him leave to be absent I know not: therefore my Son George is under a necessity of makeing good use of his time while he shall stay with you.”

There was indeed an immediate crisis that October when George wrote to his Father declaring his intention to become a chaplain of the East India Company and leave on an imminently departing ship to make his fortune trading in Asia. This drew a stern reproof: “I beleive ye Bishop will not give you leave to be so long absente; and have a care of loseing ye Substance in catching at ye Shadow. I fancy your worthy good Friend Mr Principal will not advise you to this dangerous long Voyage.”

The scheme was quickly abandoned but the discontent remained. At the end of the month George proposed trying to become a chaplain in Parliament; “I shall not encourage you,” Fleming drily noted.

The following April, George clearly expresses his feelings about his parish while asking his Father to help secure a lectureship (position as a preacher) in London: “I remember Sir among the Arguments you were pleas’d to make use of to convince me of my error in refusing Holy Orders, you laid not the least stress upon that of Church Preferment: from whence I collect that its your desire as well as mine that I should move in as high a station in ye Church as I may; but I am satisfied the way to it is not by Aspatrick, for I take an old country Div[ine]. to be as unfit for any other, as a superannuated Fellow of a Coll[ege], for a Country Cure.”

This again drew a sharp response from his Father: “I hear, that my Lord Bishop is not well pleased that you come not down according to your promis unto his Lordship. Whosoever doats ‘upon what they want, & undervalues what they have, will never live contentedly. If you would be advised to come down shortly, & to serve your own cure, at least until you can procure a curate upon reasonable terms; I think it would be much better for you, than any Lecturers place in London that I can be able to procure you. A man who designes to be great, must not neglect little things: for otherwise he often catches at a shadow, and thereby loseth ye substance. I should think it would be a recreation for you to be here sometimes, & to be sometimes at Aspatrick; & when you are so near Rose [Castle], you may more probably better your preferment. Parents can but advise, & if children will not be ruled by them, they may repent it when it will be too late.”

If no glamourous post was to be procured, George was adamant he must continue his studies at Oxford: “…I shall not be oblig’d, to put so long a stop to my studies, as a Northcountry journey will cause…” He wrang several extensions of his time in Hall from his increasingly reluctant father: “But its something hard upon me, both to procure you a good Liveing, & to get you in ye minde to enjoy it… If you be not well instructed in those Arts whereof you are, or should be master, you must blaim your selfe in not having imployed your time better. Some ye longer they shall continue in ye University, they grow ye lazier, & less serviceable both to Church & State.”

George was, however, not left without some obligations to his parish, his Father writes in November 1695: “My Lord Bishop is content with your staying this winter at Oxford; but you must provide sermons against ye Spring.” And again in February 1696: “I would have you make it your main business to fit your selfe with many good sermons.”

In his desire to extend his sojourn in Oxford, George enjoyed the support of his Principal, who wrote to Rydal on George’s behalf in February 1697: “I confess, I have as little kindness for non-residence as any Body; and I am far from wondering my good Lord of Carlile should be earnest for his attendance upon his Duty. But I must needs say, if ever a Dispensation in this matter may be thought reasonable, I am satisfied ’tis in your Sonn’s Case. He’s far from Loitering here in this place for his pleasure…but has been as close and Severe a Student as any man among us. He has made his Profession entirely his business, and ’tis and has been all along since he took Orders his concern to qualify Himself for the Service of the Church of England.”

Although Mill is undoubtedly sincere there is also an element of self-interest at work in his desire to keep George studying, and so paying battels and fees, at the Hall as long as possible. He proposed a compromise that his student after nine years in residence at the Hall should depart at the beginning of Michaelmas term 1697. Fleming and Smith both agreed. Fleming took the opportunity to send Mill one last gift, though one perhaps less welcome than £10 in cash – a large pie made of potted salmon from his estates: “I have sent a charr-pot for your most Honor’d Principal, & I shall pay for ye Carryage of it.”

“…He returns back…as truely and exemplary a Religious and good man, and every way qualified for his Function”: The ecclesiastical career of George Fleming

On George’s departure, Mill sent with him letters of praise and recommendation to both the Father and the Bishop: “For indeed I am very unwilling to part with Him, if he could be spar’d from his Cure. He has ply’d his Studies of Divinity very hard, for the Time my Lord of Carlile has excusd him from Residence. And I am sure he returns back to Him as truely and exemplary a Religious and good man, and every way qualified for his Function, as any his Lordship has in his Diocese. And consequently, I promise and assure my Self, he will give Him a particular Room in his favour.”

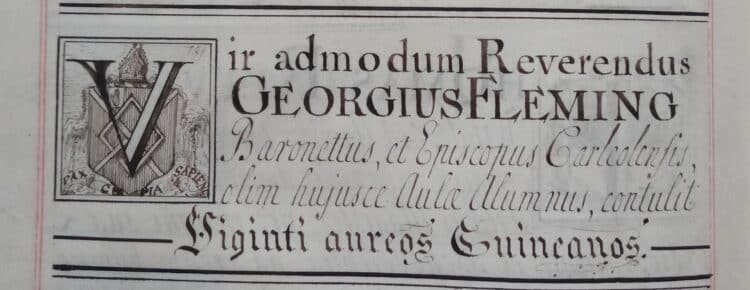

Indeed, George’s progress on his return was impressive. By June 1698 he was living in the Bishop’s Palace at Rose Castle and serving as Smith’s Chaplain. The last letter that Daniel Fleming received before his death in 1701 was from George giving an account of his installation as a prebend (canon) of Carlisle Cathedral; he became Archdeacon in 1705, returned to the Cathedral as Dean in 1727 and finally was consecrated Bishop of Carlisle in 1734. At which point, to close a circle, he became the second Bishop of Carlisle to have an entry in the Hall’s Benefactors’ Book which records the gift of £20 to his alma mater.

Category: Library, Arts & Archives

Author

James

Howarth

James has been St Edmund Hall’s Librarian since May 2018. He is responsible for maintaining and developing the library’s collections – including the historic and special collections that are housed in the seventeenth-century Old Library and is keen to promote their use in research, study and outreach.