Britain, Europe, and Politically Convenient Myths

4 Mar 2020|Mikko Lievonen

- Research

Writing about contemporary political history carries certain unique occupational hazards. The closer we get to our own day, the greater the likelihood that some half-forgotten historical debate connects with present controversies. I am probably not the only historian of post-war Britain who lives with the irrational fear that some day, during some academic disputation, an audience member of advanced years stands up and declares: ‘That’s not how it went. I know – I was there’. I am fairly certain medieval historians do not have this problem.

Such thoughts were at the back of my mind when I agreed to write about the emotionally charged topic of Britain and Europe. Part of my doctoral thesis deals with the early years of Britain’s membership in the European Union – or as it was originally known – the European Economic Community (EEC). The events of the early 1970s are recent enough to lie within the remit of popular memory, but at the same time, distant enough for the emergence of myths.

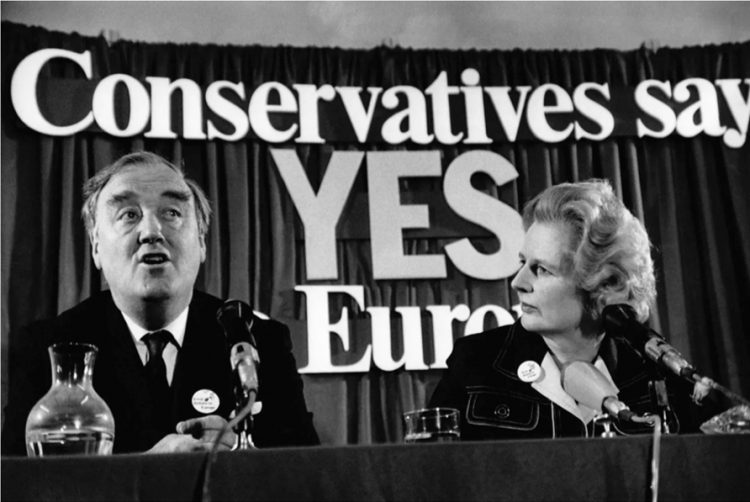

As any History undergraduate worthy of his or her black robes should be able to tell, Britain joined the EEC in 1973, during the Conservative government of Edward Heath. Two years later, with Harold Wilson’s Labour in government, the British voters were given a say in a ‘leave or remain’ referendum. The result was a resounding 67 percent for staying in the EEC.

Readers interested in the pivotal European debate of the early 1970s should look no further than Robert Saunders’s excellent Yes to Europe!, the most recent and thorough exploration of the topic. My own research provides some marginalia to the story by focusing on Conservative and Labour policy experts. Before the ascendancy of the think-tank and the advertising agency, both parties had small in-house policy units, known as research departments. The archives of the research departments offer us a detailed look at the process of policy development and the intellectual influences behind party policy.

It may be hard to believe now, but there was a time when the Conservative Party was a staunch supporter of European intergration. The party had campaigned for British membership since 1961. Once Edward Heath became the party leader in 1965, the Conservatives made EEC membership a pillar in their programme of national modernisation. In the early 1970s the Conservative Research Department was ardently pro-European. The department’s experts believed that intergration with continental economies would expand export opportunities and increase competition, forcing British industry to modernise.

But importantly, the Conservative policy unit was not only interested in the economics of membership, but also in the EEC as a way of maintaining Britain’s diplomatic prestige and relevance. The EEC held the promise of a new international identity for a post-imperial Britain. Britain had to be in the club, or risk being left out in the cold. The Conservative Research Department even argued that Britain should throw her weight behind deeper intergration in everything from foreign policy to monetary union. In this way, Britain could shape the EEC in accordance with her own interests, acting as a leader in a unified Europe.

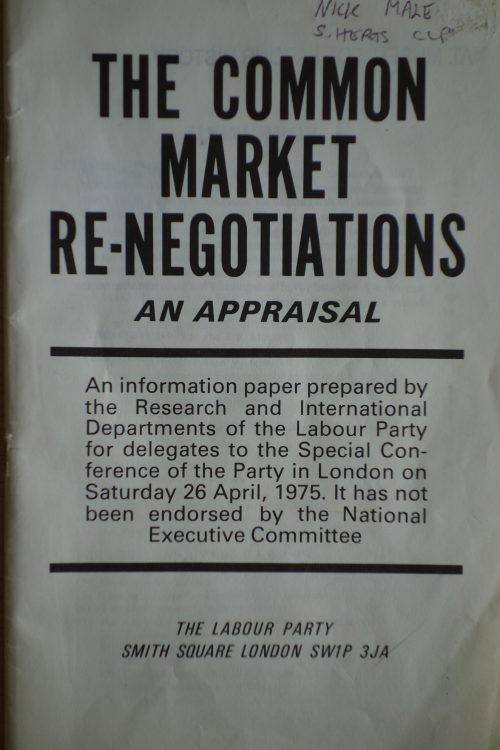

The Labour Party in the 1970s was deeply divided, but leaning towards Euroscepticism. To prevent a party split, Labour Prime Minister Harold Wilson decided to call a referendum (the parallels with Prime Minister David Cameron are rather obvious here). In the lead-up to the 5 June 1975 referendum, the Labour Party Research Department was tasked with evaluating whether the terms of EEC membership were consistent with the party’s policies. The resulting report, nicknamed the ‘black paper’ by pro-European Labour members, rejected nearly all arguments for EEC membership, whether economic or political. The Labour Party officially supported the ‘leave’ vote in the referendum.

Labour’s research department kept the flame of leftist Euroscepticism burning after the 1975 referendum. Labour experts argued that EEC membership was incompatible with the party’s socialist objectives. Committed to a radical programme of economic planning, public ownership, and trade protectionism, the party’s policy staff saw the EEC as a capitalist club intent on imposing laissez-faire economic policies on member states. Ultimately, in 1980, following a disastrous election loss, the Labour Party once again committed itself to a policy of full withdrawal from the EEC.

What can be learnt from the analyses of back room policy experts from a bygone era? According to a persistent myth, Britain joined a limited customs union in 1973, and ‘ever closer union’ with Europe was later inflicted by stealth upon unsuspecting Britons. Like most myths, this one contains a grain of truth: trade was an important consideration. But the myth overlooks the extent to which thinkers from left to right saw European intergration as a profoundly political issue. The stakes were higher than a ‘marginal advantage in selling washing machines in Dusseldorf’, as Harold Wilson once put it to Parliament.

Joining the EEC was seen as a fundamental question of Britain’s world role. This was evident in the Conservative Research Department’s keen support for deeper political union, based on an idea of diplomatic grandeur. The Labour Party Research Department’s desire to lead Britain into a kind of glorious socialist isolationism was based on an entirely different political vision. In both cases, the policy experts were attempting to outline an idea of Britain on the world stage. Such ideas were not limited to the rarefied circles of party insiders, but featured prominently in the 1975 referendum campaign. Thus, the notion of the British walking blindly into ‘ever closer union’ with the rest of Europe is revealed as nothing more than a myth, or worse, politically motivated fiction.

Category: Research

Author

Mikko

Lievonen

Mikko Lievonen is a doctoral student in History at St Edmund Hall. He recently completed a thesis titled ‘Conservative and Labour Research Departments, Economic Thought, and Party Policy, 1970-79’