Celebrating Marriage

1 Aug 2023|Emma Carter

- Library, Arts & Archives

Marriage for love, marriage for financial stability, marriage for power – thought on matrimony has changed considerably over time and not necessarily in progressive order. Although deeply rooted in religion and patriarchy, marriage has evolved as a social norm to suit each successive generation. Today we uphold it primarily as a celebration of love between equal partners. Staff members at Teddy Hall are celebrating multiple weddings in 2023, to mark the occasion an exhibition has been put together of Old Library books on the theme of marriage. This blog post is a snapshot of some of the works on display.

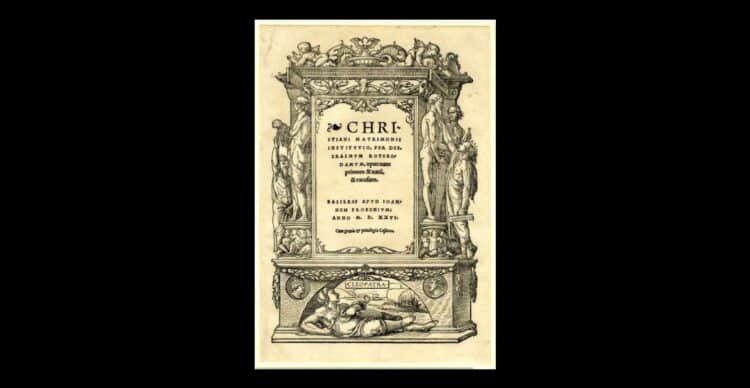

In the earliest book displayed in this exhibition – Institutio Christiani Matrimonii (SEH MM 120 (1)) published 1526, Erasmus’s views on marriage were more progressive and humanistic than those of other Renaissance thinkers. He believed that marriage should be based on mutual affection, compassion, and intimacy. His work also advocates freedom of choice in one’s partner and criticises the calculated practicality of parental involvement in the betrothal and the financial ramifications of matches. Furthermore, unlike Martin Luther, Erasmus believed that celibacy was not necessary for spiritual purity. Marriage was a legitimate way of life, especially in its hope of begetting, rearing, and education of children.

Unfortunately, the patriarchal view of marriage continued to thrive after Erasmus and various 17th Century conduct books such as A Bride-bush: or, A direction for married persons (SEH JJ 124 (1)) were published espousing the absolute dominance and authority of the husband in the relationship. To the modern eye, A Bride-Bush represents a shocking example of outdated views and veiled approval for domestic violence. However, it is perhaps a small comfort that the sheer number of conduct books like this printed by the male-dominated publishing industry may also reveal how difficult it was to keep women in subservient roles.

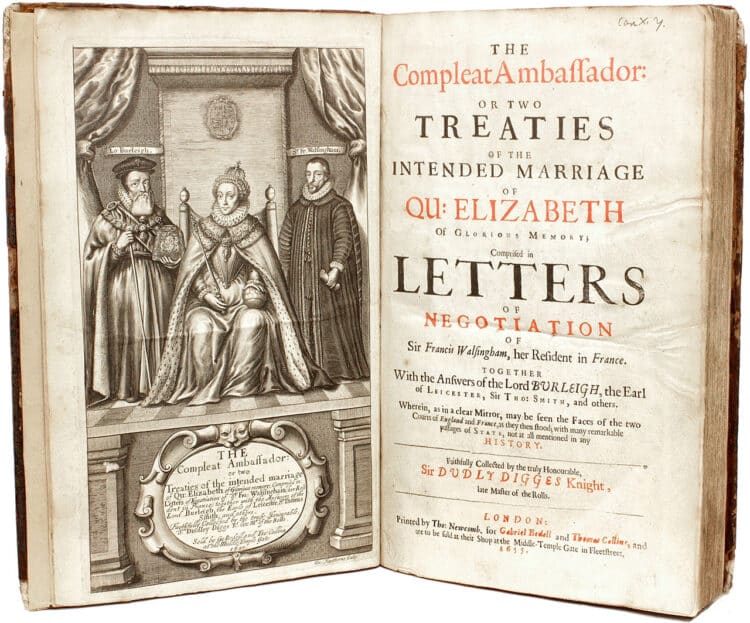

Women with power as great as Elizabeth I had ample authority to choose their own path, but even the ‘Virgin Queen’ did flirt with the idea of marriage. Although notorious for never having married, Elizabeth enjoyed many quite romantic courtships throughout her life, she even proposed marriage to Francis, Duke of Alencon, presenting him with a ring from her own finger as a pledge. However, the next morning, after a sleepless night, she decided to sacrifice her personal affection for regnal duty. As Henry VIII’s divorce caused such political upheaval, it is unsurprising why Elizabeth I ultimately rejected marriage. Although a master of matrimonial diplomacy, finding advantageous matches for her courtiers, in 16th Century England it seemed impossible to marry without forfeiting some of her power. This book (SEH Fol. N 14) is filled with correspondence between the Queen, Sir Francis Walsingham (ambassador to France) and Lord Burghley (Lord High Treasurer) about her closest prospects and the repercussions her choices may have had on the nation.

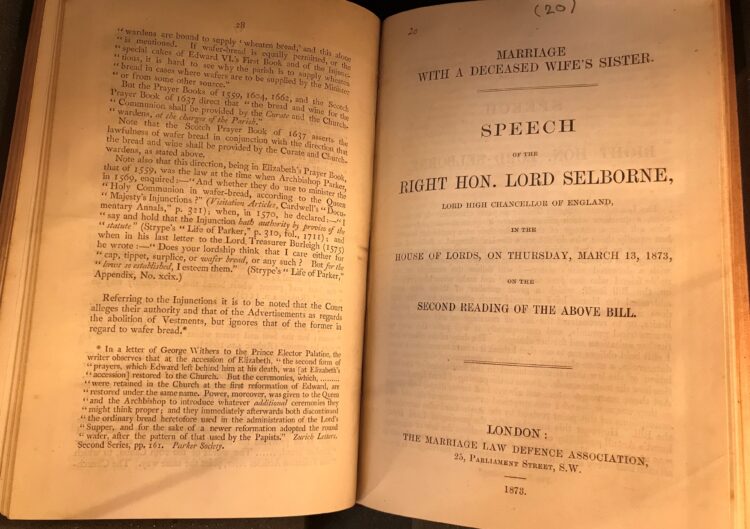

Henry VIII also altered the law to allow his marriage to Anne Boleyn’s cousin Catherine Howard. The Church had long been warning against the dangers of incest, but without an understanding of hereditary genetics (later explained by Gregor Mendel in mid-19th century), the Church’s definition of ‘near kin’ was much wider than ours today. Indeed, much of the 19th century was spent debating the legality of marriage between a man and his ‘deceased wife’s sister’. In 1835 England outlawed all marriages forbidden by the Table of Kindred and Affinity in the Book of Common Prayer, and after robust opposition by Lord Selbourne (see: SEH 1356 (20)), the ‘deceased wife’s sister’ clause was not repealed until over 70 years later in 1907.

Ultimately, legislation makes the greatest impact on marriage. The Marriage Act 1836 legalised civil marriage among non-Anglican religious groups which allowed them legal protections that common-law partnerships did not. The Married Women’s Property Acts 1870 and 1882 gave women the right to their own income and protected their inheritance. It is regrettable that LGBT+ couples were not legally recognised until civil partnership was finally legalised in the UK in 2004, followed painstakingly by same-sex marriage in 2014. However, it is fantastic to see new publications highlight stories of same-sex marriages in centuries past. From tales of Female Husbands to comprehensive studies of London as a Queer City over centuries, LGBT+ histories are becoming more integrated into historical research.

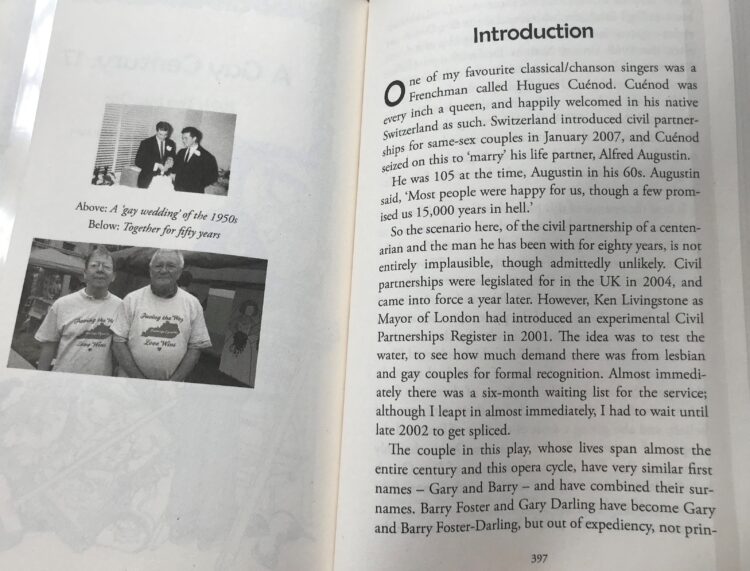

More recently, Peter Scott-Presland (1968, English) has published two volumes of dramatic works named A Gay Century (SEH/SCO AR) which were performed for online audiences during lockdown 2020. Peter is the founder/director of Homo Promos, the oldest LGBT theatre company in the UK. The epic project earned Peter the International Lesbian and Gay Cultural Network Award 2021. The introduction to ‘2001: Two into One’ gives a charming first-hand account of the slow introduction of same-sex civil partnership by the Mayor of London to test the waters, despite evident overwhelming demand from the LGBT+ community. Peter and his partner were one of the first to apply for civil partnership and after a lengthy waiting list tied the knot in 2002.

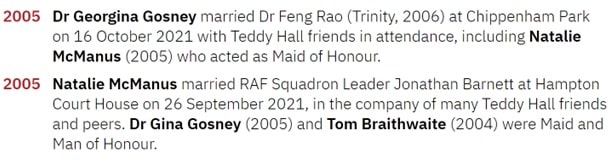

It is always a joy to share in De Fortunis Aularium and our own Teddy Hall Magazine has published marriage announcements since its second ever issue in 1921. In these parallel announcements from 2021 it is particularly lovely to see Aularian friends participating in each other’s wedding parties.

Did you know? – The History of Wedding Traditions

- The white wedding dress was popularised in the UK by Queen Victoria. When she married Prince Albert on 10th February 1840, she wanted to wear lots of lace – her dresser’s explained that lace would show up best in white.

- Engagement and wedding rings are worn on the fourth finger of the left hand because it was once thought that a vein named the ‘Vena Amoris’ in that finger led directly to the heart.

- The tradition of matching bridesmaids dates back to Roman times, when people believed evil spirits would attend the wedding in an attempt to curse the bride and groom. Bridesmaids were required to dress exactly like the bride in order to confuse the spirits and bring luck to the marriage.

- Ancient Norse bridal couples went into hiding after the wedding, and a family member would bring them a cup of honey wine for one ‘moon’ (month)—which is how the term “honeymoon” originated.

- German composer Felix Mendelssohn wrote the “Wedding March” for an 1842 production of Shakespeare’s A Midsummer Night’s Dream, and “Here Comes the Bride” was the Bridal Chorus from Richard Wagner’s 1850 opera Lohengrin. Wagner’s piece was made popular when it was used as the processional at the wedding of Victoria the Princess Royal (Queen Victoria’s Daughter) to Prince Frederick William of Prussia in 1858.

The full exhibition will be available to see in the Old Library until September 2023. Please send an email to library@seh.ox.ac.uk to book an appointment.

Category: Library, Arts & Archives