Discovering the Earthworm’s Half a Billion Year Old Cousin

16 Jun 2020|Dr Luke Parry

- Research

Earthworms and leeches are worms familiar to humans and belong to a larger group called annelids. Annelid worms are among the most abundant and diverse types of animal alive today and have colonised environments from soils on land to the ocean, where they first evolved over 500 million years ago. Although they have soft bodies that rapidly succumb to decay upon death, annelids have left a rich fossil record in special and rare geological sites where features such as skin, guts and muscle tissue have been preserved. Fossils such as these are the focus of my research and I recently described the oldest annelid worm that belongs to a group still alive today, that lived in what is now China about 514 million years ago.

The fossilised remains of the soft parts of annelids are now known from a number of sites in the Cambrian Period (about 540 to 485 million years ago). This is an important time during the history of life in which the major groups of animals first appear in the fossil record and diversify rapidly, forever changing the planet and its environments and ecosystems. These earliest annelids are a type of worm called polychaetes, which means many bristles, in reference to the stout, hardened projections that sit at the ends of their fleshy limbs. Polychaetes in the modern ocean have a diversity of form and live in many different ways including as active ambush predators, but also as sessile animals that filter food from the water column. Their success is partly owed to their segmented bodies, with their many repeated body units (segments) allowing them to be highly adaptable.

These ancient annelid fossils have told us much about what their earliest relatives looked like and how characteristic annelid features evolved. This even includes fossilised remains of annelid brains and nerve cords that I described in a paper in late 2019 from a site in British Columbia, Canada called the Burgess Shale. This study showed that complexity in the annelid nervous system arose very early, and that many groups of living annelids that have simple nervous systems have lost traits over evolutionary time.

Until now however, the polychaetes we knew of from the Cambrian period were what we refer to as stem group annelids. This means that on the annelid evolutionary tree these early fossils branched before the origin of the last common ancestor of annelids alive today. All of these polychaete annelids have large fleshy limbs equipped with many bushy bristles, features that are mostly known today in groups that active crawl on the seafloor, showing that the earliest annelids were active animals.

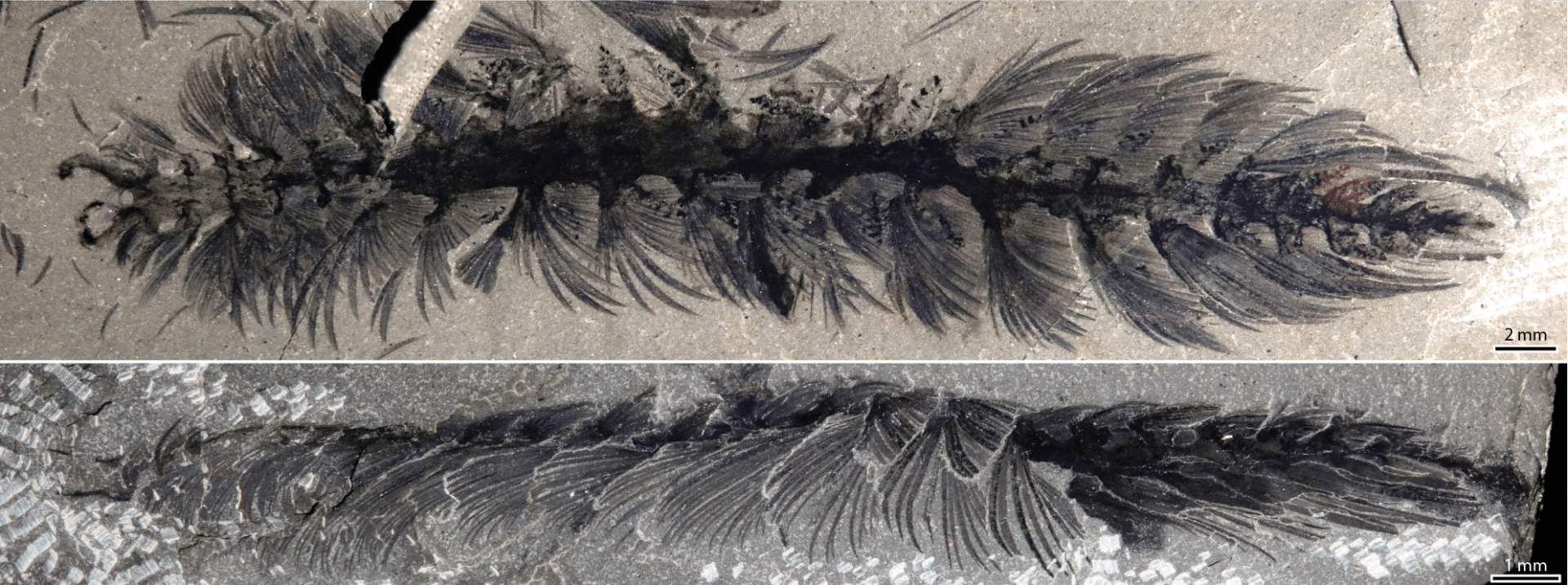

This all changed in a paper published this week in Nature, where along with an international team of scientists I described a new polychaete worm that is wholly unlike any other fossil from the Cambrian. The fossils were collected in Yunnan Province in southwestern China, from rocks that are dated to slightly older than 514 million years ago. We named this new fossil Dannychaeta tucolus, with the genus named for Danny Eibye-Jacobsen from the Natural History Museum of Denmark.

This new fossil is not as well preserved as some other examples from this time period, but it has features that mark it out as truly unique. The head of the animal is pronounced and equipped with two long tentacles (called palps in the world of annelid worms), followed by a slightly stouter portion of the body, with the back part of the animal being long and slender. In general, the appearance Dannychaeta closely resembles an unusual family of worms called the Magelonidae, a group that is relatively understudied, but occurs globally in the ocean including in coastal environments of the British Isles. Biologists studying living annelids have recently discovered that this group is an ancient branch in the annelid tree of life, and it was previously puzzling why worms like them were not known from the early fossil record.

As the oldest annelid that can be assigned to a living group, Dannychaeta tells us that the annelid ancestor is older than we thought before. It must have lived before 514 million years ago. Previously, our earliest evidence for polychaetes that are similar to those alive today were much younger, at about 490 million years old.

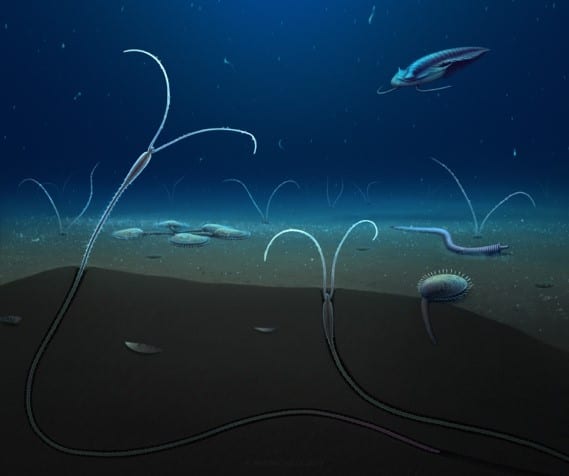

Unlike all of the other annelid fossils known from the Cambrian period, some specimens of Dannychaeta show that it lived inside a dwelling tube and was therefore sedentary and sessile. Many different types of annelids alive today live inside tubes but this is our early evidence of a kind of lifestyle that is now commonplace in the group. Although there are many fossils of tubes that animals would have lived inside from the Cambrian, we don’t know what sort of organisms occupied them, as tubes preserved with the animals inside are extremely rare.

With the new evidence provided by Dannychaeta, we now know that annelids were living many different kinds of lifestyle over half a billion years ago when we have the first evidence for them existing. This includes primitive forms like Canadia spinosa that scuttled around on the ancient seafloor and now forms like Dannychaeta that lived very inactive lives, protected in the sediment in the safety of their tubes.

Category: Research

Author

Luke

Parry

Luke’s research aims to understand a major event in the history of life referred to as the ‘Cambrian Explosion’, a geologically brief interval during which all of the major groups of animals first appear in the fossil record.