A Soldier’s Bivouac, Incense for Marguerite, and Gambling Debts. Eighteenth-Century Fugitive Poetry and Everyday Note-Taking

16 Jun 2023|

- Research

Trying to pin down the complex and multifaceted phenomenon that Eighteenth-century French contemporaries called ‘poésie fugitive‘ is not an easy task. Especially so, if one wants to avoid projecting modern ideas about how poetry should look (and sound) like on texts and interactions with texts that clearly follow a different set of rules. Things get more complicated, still, because the term can signify a generic distinction between light, often humorous, amorous or slightly frivolous verse and more substantial, more serious texts, but also denotes the sociable nature of these poems and a particular mode of dissemination/publication. ‘Fugitive’ verse is fugitive, according to Diderot’s Definition in the Encyclopédie, because it escapes the author’s quill and, subsequently, his portfolio; it circulates first in manuscript, only later to be published and collected. Hence, fugitive poetry is poetry that escaped its own ephemerality, precisely, by fleeing the private portfolio and becoming a public text.

This is not the place to attempt a definition of ‘poésie fugitive’, nor to further complicate matters by taking into consideration that the private nature of fugitive poetry might, in some cases at least, be nothing more than a ruse to render the text (or its author/addressee) more interesting. Rather, I want to stress how widespread this form of poetic production was throughout the Eighteenth century and how highly contemporaries thought of fugitive poetry. Again in the Encyclopédie, d’Alembert claims that the number and quality of Voltaire’s fugitive poetry alone would have sufficed to immortalise more than one author.

That poésie fugitive was by no means a sociable practice confined to aristocratic circles or the past-time of well-known authors when they needed a break from their literary activities in more respectable genres becomes clear when looking at contemporary comments and, sometimes, complaints about the sheer volume and ubiquity of minor verse. We may safely assume that what we know today is only the tip of a poetic iceberg and that many of these texts have not left any trace at all. A quatrain by a celebrity like Voltaire is likely to be carefully preserved, widely circulated, and, eventually, published in print. Much less so the poetic attempts of an everyman.

Finding actual, material traces of writing, reading and interacting with fugitive poetry throughout the Eighteenth century and apart from major or minor celebrities is tricky and much has to remain speculation. In the rare instance where we can find traces of actual poems, we might also find that they provide little in terms of aesthetic pleasure. Nonetheless, they are significant witnesses to a social convention, and, in some cases, the material objects and practices associated with it. A few witnesses of the more mundane use, reuse and production of fugitive poetry have, however, survived, and they are particularly interesting in their materiality. One of the examples for the widespread use of fugitive poetry in all kinds of mundane contexts is this ‘book’ of candy-wrappers made out of poetry. Another intriguing example is a series of almanac-style publications with added notebook-sections where fugitive poetry was part of the printed sections and/or manuscript notes. These, too, have survived (at least in a few copies) because they are bound as a book and contain a printed almanac or other printed material that made them seem worth archiving (and provided bibliographical data like a title to properly anchor them in a library catalogue).

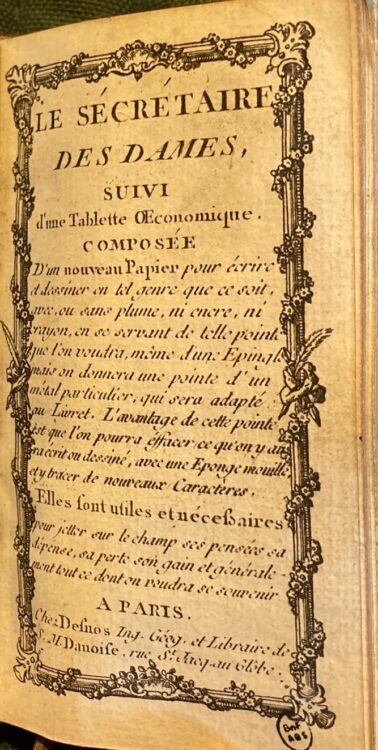

A wide variety of these almanac-cum-notebooks can be found,[1] but this is not the place to go into more detail. Instead, I will briefly highlight two examples to give an idea of these items and the diversity within this type of book-object. Both are printed in Paris by Desnos and Jubert respectively and date from (about) 1772 and (about) 1790.

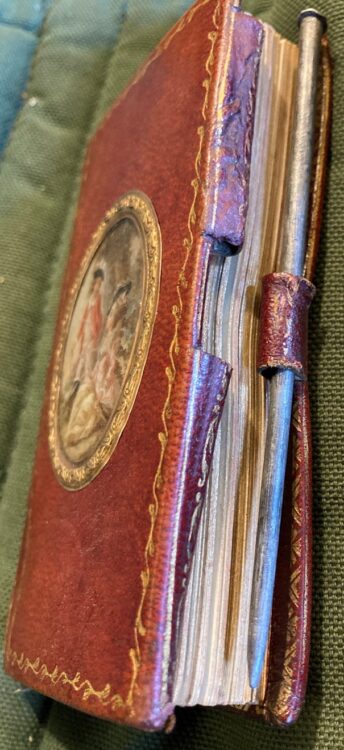

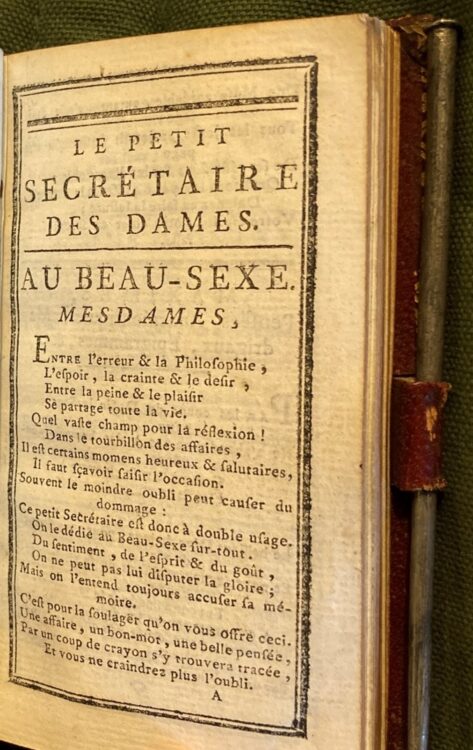

The first example, the earliest I have been able to find so far, is specifically aimed at a female public. Its first section is entitled ‘Secrétaire des Dames’ and the copy held at the Bibliothèque de l’Arsenal (RESERVE 16-Z-20527) has a miniature painting in an oval frame on the upper cover and could be closed by inserting a metal stylus in three loops made of red leather.

This stylus, very much resembling a nail and lost in copies of other volumes, together with a type of ‘nouveau papier’ is advertised as a novelty on the title page and notes taken with it supposedly are easy to erase, rendering the notebook reusable.

Putting aside this ‘technological’ novelty (which might not be as new as claimed)[2], the way in which this volume combines a first section of printed poetry with a somewhat pre-structured space for personal notes is, in fact, new. And it is telling in the way it hints at the potential kinship between fugitive poetry and a personal notebook: both are, in a first instance, a private affair. An ‘Avis’ at the beginning of the second section states that the notes can be deposited in the following pages ‘comme dans le sein d’un ami fidèle’. More practical is the opening poem itself that addresses the female target audience of the volume and, in a gendered language bordering on misogyny, stresses the utility of the notebook in unburdening the (female) memory by taking notes of affairs, ‘belles pensées’ and bons mots.

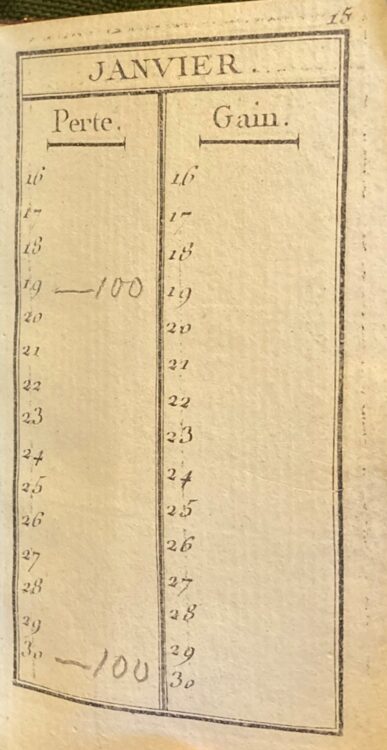

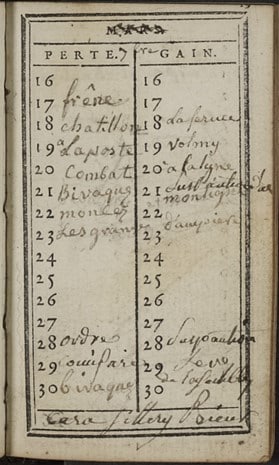

The copy in the Bibliothèque de l’Arsenal, however, only has very few notes, most of which seem to be tallies recording gambling results – and no poetry is to be found after the printed first section with its fables, epigrams and other poetic genres.

My second example dates from c.1790 and is maybe even more interesting because, firstly, the copy held by the Bibliothèque Carré d’art in Nîmes and digitally available in Gallica contains more handwritten notes and, secondly, because it is published (and used) during the French Revolution and shows that fugitive poetry by no means disappeared with the political and social upheavals. At first glance, it would look as though there is little room for poetry in this book. Entitled La cocarde citoyenne and dedicated à la nation, the first part is no longer catered towards women who might want to unburden their memoires or their hearts, but it details the events surrounding July 14, 1789. And, likewise, in the notes-section no account of gambling gains or debts is to be found, but, rather, one can reconstruct what seems to be the route of a soldier whose regiment took part in the Battle of Valmy, site of the first victory of the French army in the Revolutionary Wars. Making use of the columns of the notebook intended for recording gains and losses, he traces his steps in July/August 1792 from Melun eastwards to Toul and Metz and then back westwards towards Valmy where he seems to have arrived the day before the battle (September 20, 1792).

In other pages there are records of pay he received or of people he met and their addresses. The only hint of poetry in the printed section is the rather pompous poem at the end of the preface, a patriotic call to arms ending in a promise of freedom and the end of the abuse of absolute power to the revolutionary reader:

Ainsi faisant, tu détruiras,

Tous les abus absolument.

Et d’esclave tu deviendras,

Heureux & libre assurément.

The poetic muse of the note-taking soldier who used this copy, however, seems to have been inclined to less bellicose subjects and much more in line with ‘poésie fugitive’. For him, it seems, poetry was reserved for amorous subjects. At one point he exclaims ‘Quelle est belle, la charmante Charpentiers’, and while this is not quite poetic yet, it is immediately brought back to even more prosaic terms by the following notes on received pay. On two occasions, however, there are proper poems (in well-formed, if not particularly melodic octosyllables), both dealing with amorous matters. One of them praises its addressee and is clearly intended as a poetic gift:

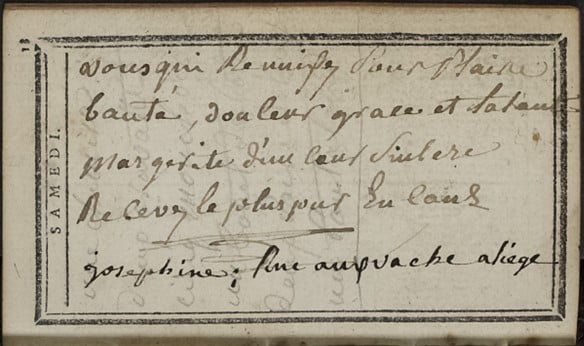

Vous qui réunissez pour plaire

beauté, douceur grâce et talents

Marguerite d’un cœur sincère

Recevez le plus pur encens.

However, the soldier-poet might not have been very steady in his attentions to Marguerite, for directly below these lines we can read the address of a certain Josephine – the metre would accommodate her name in the poem, too. In the case of the second poem in this volume, the contrast is not with another woman’s name but, again, with columns of numbers following immediately on the page.

It is precisely this proximity between poetry and the everyday life which renders these documents interesting. They attest the degree to which poésie fugitive permeated many aspects of life, from note-taking in a volume with printed poetry, to writing one’s own poetry in a revolutionary notebook to wrapping sweets in verse – all this without the boundaries we, today, tend to draw between the mundane and the poetic.

[1] Two (at least) are held at the Bodleian: A collection of different almanacs (Vet. E5 g.9), this one, alas, without a trace of poetry, and, in the Douce collection (Douce A 336), a copy of an illustrated almanac showing ‘Situations intéressantes’ with manuscript English translations/imitations of some of the poems contained in it.

[2] See, for similar examples in 17th century England, P. Stallybrass et al.: ‘Hamlet’s Tables and the Technologies of Writing in Renaissance England’, Shakespeare Quarterly 55.4 (2004), pp. 379-419.

Category: Research