God, Gold, and the Gospel of the Poor in the Early Middle Ages

10 Feb 2021|

- Research

Is the message of the Christian Church good news for the poor?

As an Anglican priest, I’d like to give an unqualified Yes, but as a historian I have to say the Church’s record is mixed.

We have reasons to say Yes. At a synagogue in Nazareth, Jesus described his mission and person in liberative terms, reading the words of the Hebrew prophet Isaiah: “The Spirit of the Lord is upon me, because he has anointed me to preach good news to the poor” (Luke 4:18, citing Isaiah 61:1).

In late antiquity, too, the Church’s understanding of charity and social solidarity gradually transformed truly appalling classical attitudes toward poverty, along with individual and communal practices of almsgiving in the Roman Empire, as Richard Finn has argued. And from the Middle Ages and into the modern period, numerous Christian institutions — monasteries, almshouses, and hospitals, for example — were dedicated to alleviating the worst effects of poverty, while an emphasis on reciprocal hospitality marked society (see the work of Peter Brown, Michel Mullat, Brian Pullan, and many others).

The legacy of these efforts and attitudes remain with us today. And, surely, we should be thankful for them.

But we also have reasons to say No, the Church is not on the side of the poor, and many of those contradictions inspire my current research. For example, in the Early Middle Ages, the period I study, the monastery of Fulda was the largest slaveholding institution in Europe and one of the largest landowners.

And across the Continent, when churches were founded, various laws and canons stipulated that they should be endowed with lands and people to work them, with the transfer of people to churches coming as a corollary to the receipt of land donations (see research here and here). Charlemagne’s advisor, Alcuin of York, a deacon in the church and a leading theologian, was said to control estates holding over 20,000 slaves. (To be fair, this was an accusation from his enemies!)

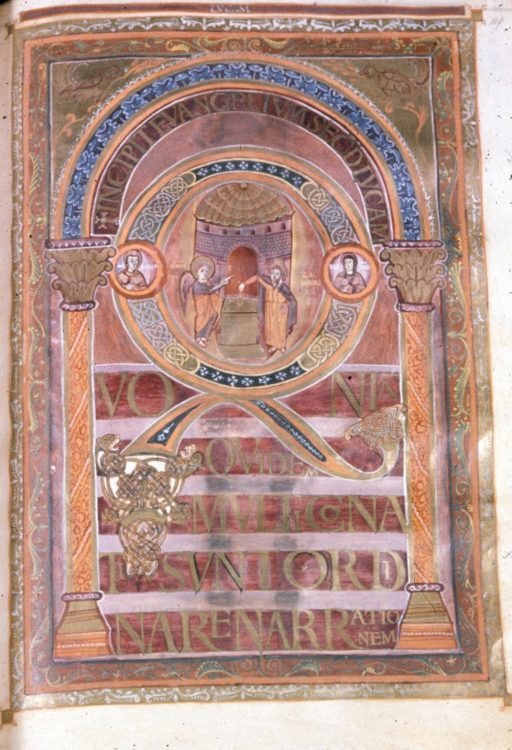

To put all this another way: This was a time when Church and society were interwoven in a way we can hardly imagine. This was a time when rulers had the words of the Gospels written in shining letters, as in the ‘Golden Gospels’ produced at the court of Charlemagne and Louis the Pious. This was a time when many good and noble public works took place. But it was also a time when slavery was central to the European way of life (see here).

After this past summer, I have found it hard not to see the continuity between this history and the contradictions and hypocrisy of Christian society during the Transatlantic Slave Trade.

So, is the message of the Church good news for the poor?

I am working at this problem from a new angle, through a project I’m calling The Gospel of the Poor and the Practices of the Powerful. In it, I focus on the interpretation and reception of the Gospel of Luke in the Early Middle Ages, with an eye to its impact on social practice. I’m interested in the story I might discover, whether positive or negative. As the liberation theologian Gustavo Gutierrez put it 50 years ago, the Christian community’s ‘successes, its omissions, and its errors are our heritage. they should not, however, delimit our boundaries’ (A Theology of Liberation, p. 50).

I’ve chosen this research focus for three specific reasons. First, biblical scholars have long noted how Luke’s Gospel emphasises those marginalised in the ancient world, and the text has a plethora of passages related to wealth and possessions. Its description of Christian faith is often uncompromising: “If you do not give up all that you possess, you cannot be my disciples,” says Jesus (Luke 14:33).

Second, the first full Latin commentary on this text was written around 714 by the Venerable Bede, well known for his Ecclesiastical History of the English People.

![011EGE000002204U00007000[SVC2] Opening of Bede’s Commentary on Luke in British Library](/asset/011EGE000002204U00007000SVC2.jpg)

But, third, the commentary went on to be exceedingly popular after Bede’s death, particularly in elite circles. Kings, nobles, bishops, monks in well endowed monasteries — basically, many of those benefitting from appalling exploitation — were among its primary readers and hearers.

Some of what they heard could have made their toes curl. Take a few lines from Mary’s song, the Magnificat (Luke 1:46-55), a text familiar to those who attend Choral Evensong.

He hath showed strength with his arm,

he hath scattered the proud in the imagination of the hearts.

He hath put down the mighty from their seat,

and hath exalted the humble and meek.

In response, Bede wrote that Mary ‘describes the whole state of the human race … through all generations of the world, the rich do not cease to perish nor do the humble cease to be exalted by the good and just dispensation of divine power’ (Commentary on Luke I:49, 52).

God is described here, and in many other passages of Bede’s work, as someone working on the side of the poor, with his face set against the powerful — actively judging those who oppress the weak.

Indeed, after canvassing much of Bede’s written work, I have discovered that he draws from Christian Scripture and tradition many themes about labour, slavery, and the use of wealth, some of which anticipate many later developments in the writings of Christian Socialists like John Ruskin or even liberation theologians like James Cone. So I’m trying to keep my eye on these modern sources and contemporary trends, even while studying Luke’s ancient Gospel and Bede’s commentary on it.

I’m still left with many questions, at this stage. Why was Bede’s work so popular? What impact did it have? And, still, is the Christian message good news for the poor?

May it be so in our time.

Category: Research