Johannes Kepler on Snowflakes or what to give someone who has everything

4 Dec 2019|James Howarth

- Library, Arts & Archives

As Christmas approaches I find myself again, as every year, wondering rather desperately what to give friends and family. This is also the dilemma that led to the writing of one of the rarest examples of early scientific writing in the Old Library: the Strena seu De niue sexangula (The New year’s gift or On the six-angled snowflake) by the German astronomer and mathematician Johannes Kepler.

What to give to someone who has everything: nothing

In 1611 Kepler was Imperial Mathematician at the court of the Holy Roman Emperor Rudolf I in Prague. In theory his salary was generous, but in fact the cash strapped Imperial exchequer often failed to pay. So when considering what he could give as a New Year’s gift to his friend and patron, Wacker von Wackfels he realised he had nothing to offer.

His playful solution was that he would give him a book about nothing. But what sort of no-thing? A grain of sand, a tiny mite, a drop of water or spark of fire, the wind perhaps. None of these seemed to fit.

He was crossing the Charles bridge in Prague pondering this problem, when suddenly he struck was by the shape of the snowflakes falling on his coat, ‘all six cornered with tufted radii.’ This was his solution; he would present his friend with a treatise on the evanescent snowflake (there is a pun here on ‘nichts’ the German for ‘nothing’ and ‘nix’ the Latin for ‘snowflake.’).

Stelluae nivales (Little snowy stars)

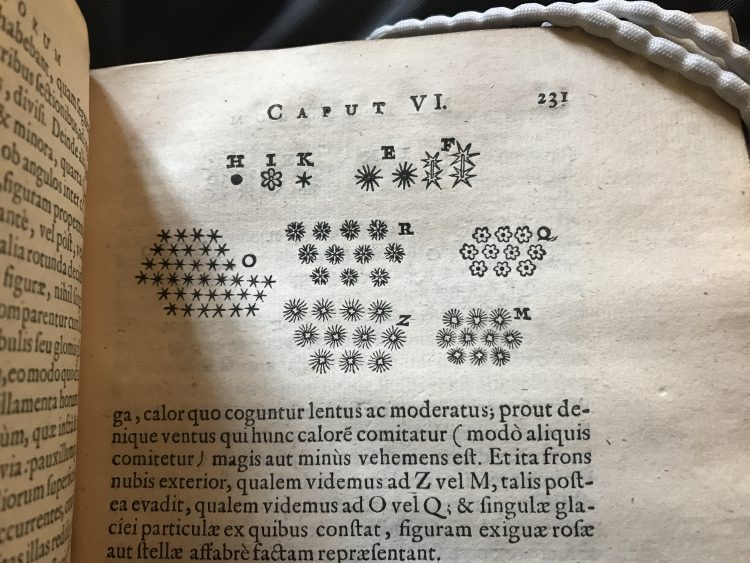

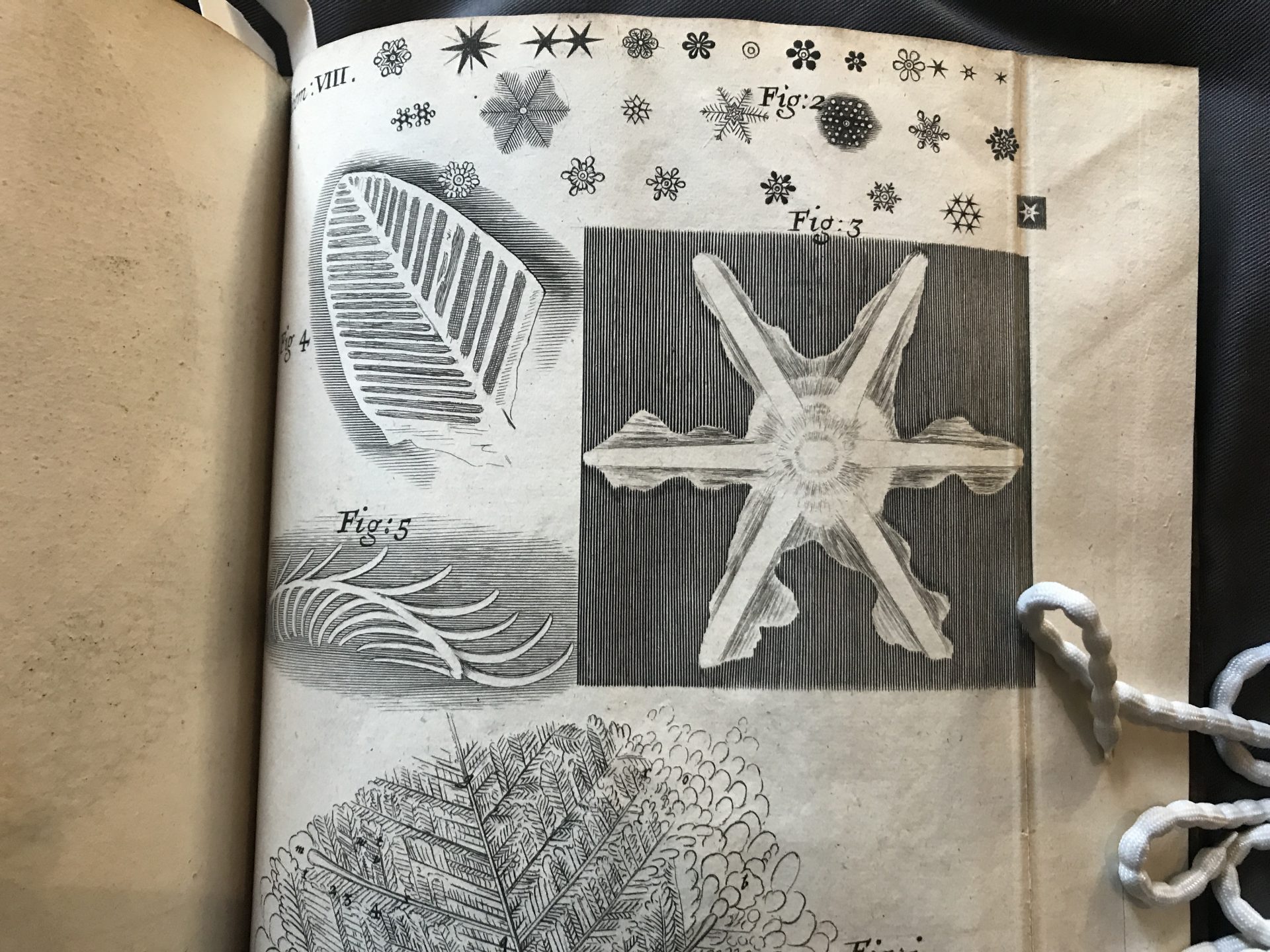

Across twenty-four pages of closely argued text and a few simple diagrams, Kepler attempts to find an answer to the question of why snowflakes always fall as small six cornered star shapes. There must be a cause he suggested, else why aren’t some four, five or even seven sided?

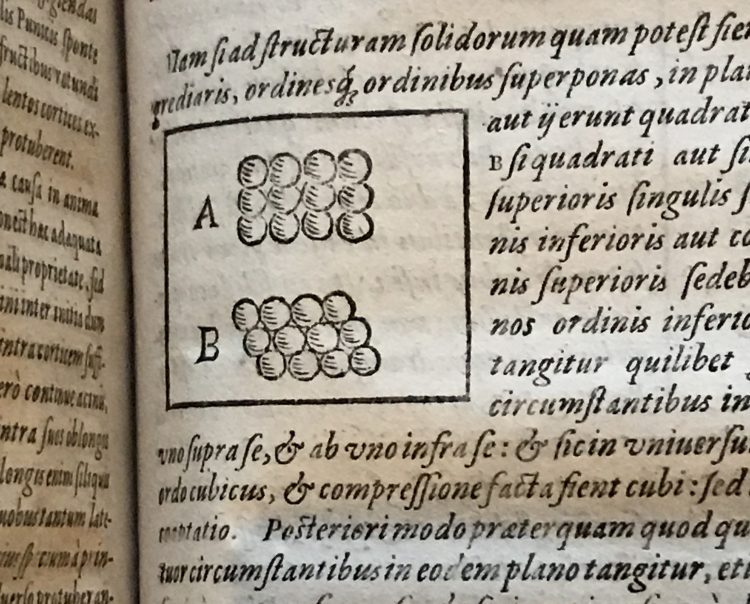

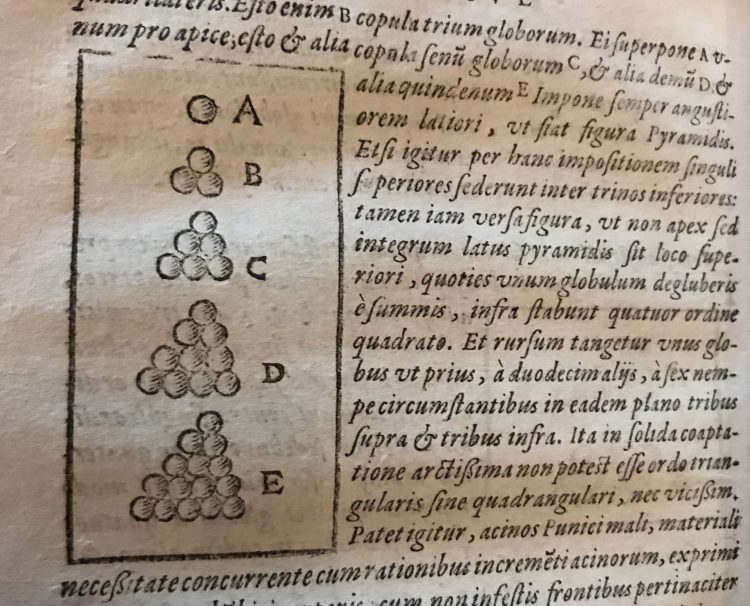

Perhaps, he considers, the hexagonal shape allows for the most efficient way of packing together the flakes of snow. He compares the shape of the snowflakes to the hexagonal cells of bee hives and to the packed arrangement of pomegranate seeds in the fruit. But then why are they flat not spherical?

Perhaps their form arises from the interplay of heat and cold, the feathery striations of the snow flakes’ arms forming like the similar patterns Kepler had noticed in the ice when steam from a hot bath hits a crack in a window in wintertime.

Kepler posits a ‘formative principle’ in nature that shapes the snowflakes, but again, why six sides? Perhaps the ‘formative principle’ does not act only for the sake of ends but aesthetically for the sake of adornment. Or perhaps there is some quality in the fluid from which snow is formed that causes the hexagonal shape. He notes shapes of other crystalline forms such as hexagonal rock crystals and rhombic shapes that can be seen in in vitriol, even a dodecahedron that could be discerned in a silver panel in the palace at Dresden. However, remarking that he is now ‘knocking on the doors of chemistry’ Kepler ends his enquiries on an inconclusive note – ‘nothing follows’ (nihil et sequenter) he closes.

‘Such an infinite variety of curiously figur’d snow’: Hooke, Descartes and the afterlife of Kepler’s snowflakes

Although short, playful in form and without firm conclusions Kepler’s investigation of snow was incredibly influential and is considered a foundation text of modern crystallography. During the 17th century his researches were continued by others including the French philosopher Rene Descartes in the Discourse on Method and by the English scientist Robert Hooke, who includes snowflakes amongst the items he examines under a microscope in his work Micrographia. Copies of both of these works sit alongside Kepler’s in the collection in our Old Library.

Like Kepler, Hooke vividly evokes the experience of studying snowflakes:

“Exposing a piece of black cloth or a black hatt to the falling snow, I have often with great pleasure, observ’d such an infinite variety of curiously figur’d snow, that it would be impossible to draw the figure and shape of every one of them…”

It was not until the 20th century that complexities of snowflake formation were fully understood. The Japanese scientist Ukichiro Nakaya managed to create artificial snow flakes in 1936 and subsequently was able to map the relationships between vapour, temperature and supersaturation which lead to their creation. His conclusions were confirmed by further experiments in artificial snowflake creation in the 1980s including by astronauts aboard the space shuttle Challenger.

Kepler’s speculations in his treatise about the most efficient way to arrange spheres in three-dimensional space waited even longer to be resolved. The ‘Kepler conjecture’, which was partly informed by his correspondence with the English mathematician Thomas Harriot on the best way to arrange cannon balls on a ship, resisted formal mathematical proof until 2015.

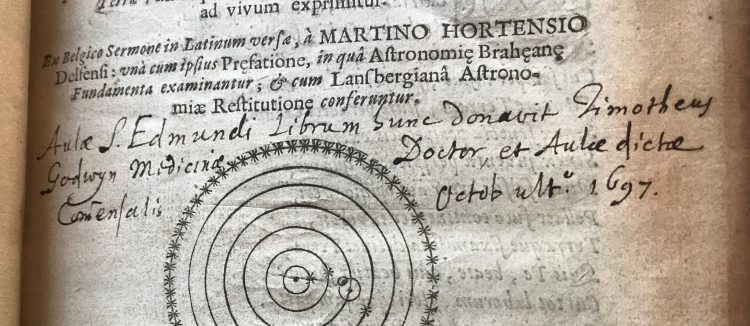

Our copy: Aulæ S. Edmundi librum hunc donavit Timotheus Godwyn

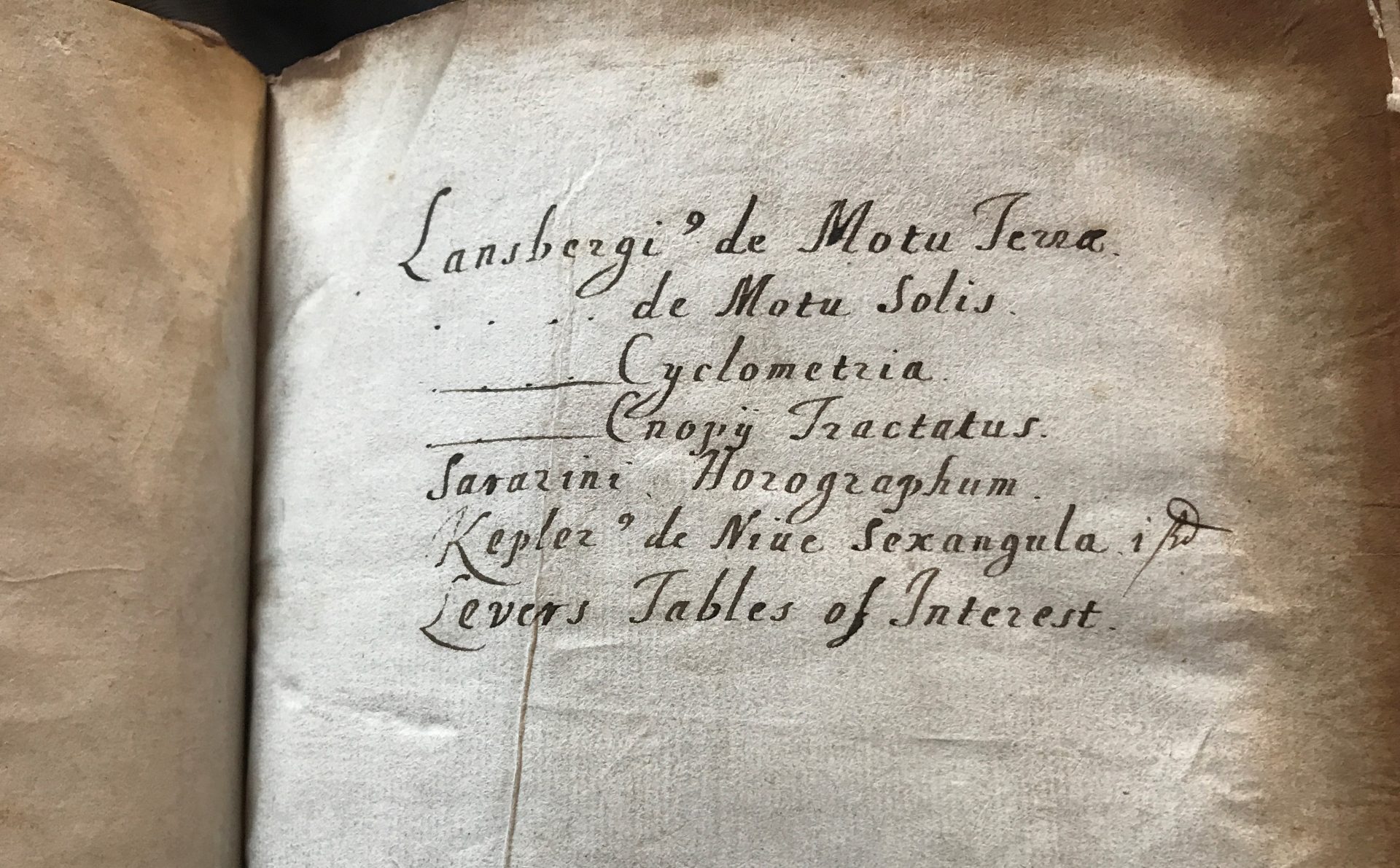

Surviving copies of Kepler’s little treatise are rare, there is only one other in a public library in the UK (in the Science Museum Library). The St Edmund Hall copy is in a sämmelband or bound collection of seven 17th century scientific and mathematical treatises. All are very rare, five of the seven are the only copies of those works in Oxford.

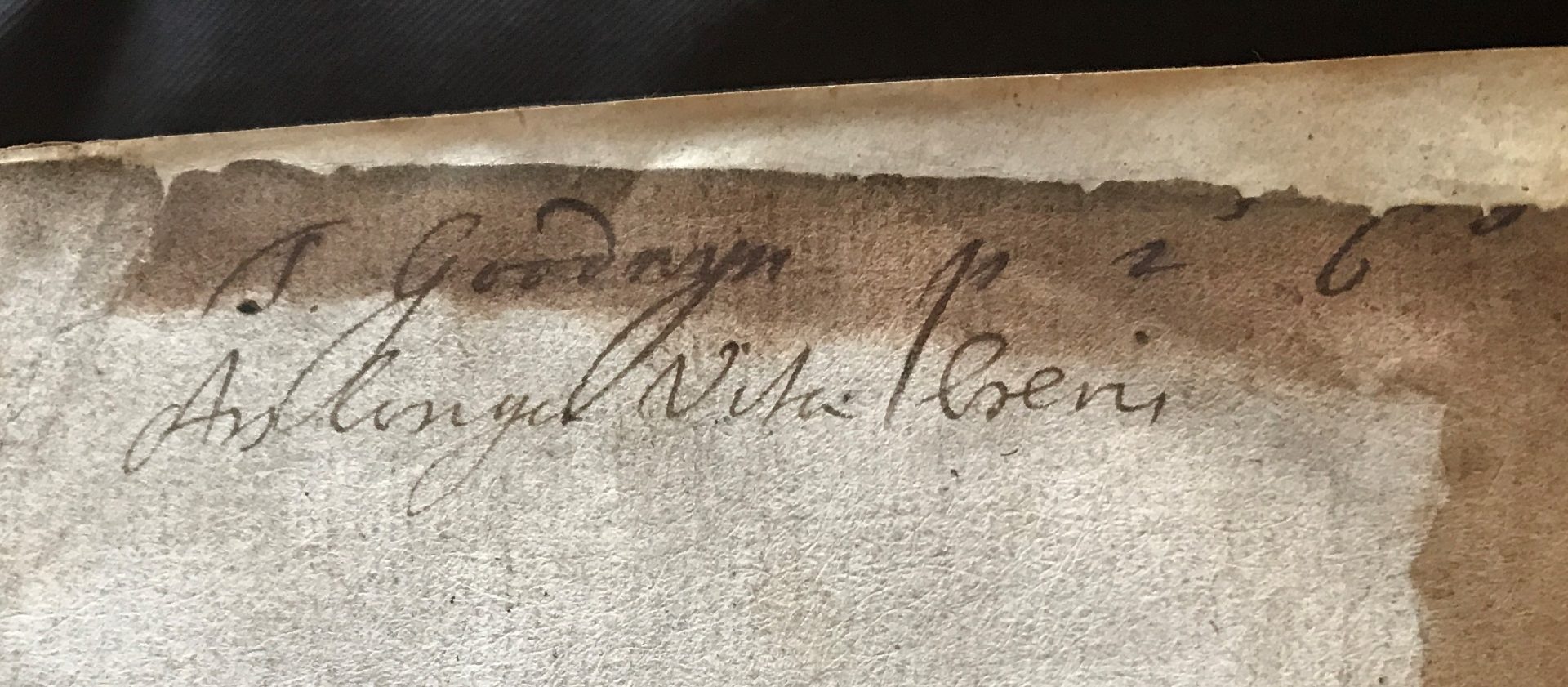

Our copy of the Strena was itself a gift. We owe the volume to the generosity of an Aularian named Timothy Godwyn (1670-1729, created MA 1697). Godwyn gave the Library the volume of treatises in October 1697 as well as two volumes of the Historiae Plantarum by the naturalist John Ray in January 1668. In both works there is a handwritten dedication by Godwyn presenting the book to the Hall.

Godwyn came from a non-conformist background, and studied first in 1686 at an academy run by Samuel Craddock, a former Fellow of Emmanuel College Cambridge who had been ejected from the Church of England after the Restoration. One of his classmates, the historian Edmund Calamy, recalled spending winter evenings with him reading Greek authors.

At this point Godwyn intended to follow a medical career. He lodged with a doctor named Edward Hulse in London and then went onto study in Utrecht in the Netherlands. Oxford and Cambridge Universities were at this point only available to members of the Anglican church.

At some point Godwyn instead decided to pursue a clerical career in the Church of England. He returned to England and was created an MA in Oxford in 1697, claiming to already have a degree from Utrecht. He was not uniformly popular with other members of St Edmund Hall. Thomas Hearne in his diary entry for June 27 1707 calls him, “a great Pretender, & a bold, confident man, & will do anything for Preferment which is all he aims at. When he was of Edm. Hall he was stingy, niggardly Fellow, & I do not remember he did any good there…” and cast doubt on the authenticity of his Utrecht credentials. Again on January 28 1709 Hearne calls him “that unworthy, illiterate Fellow.”

Hearne, did at least concede that John Mill, the Principal of St Edmund Hall from 1685-1707, had a good opinion of Godwyn. Whether or not Hearne was correct in his judgement about Godwyn’s ambition, he certainly went on to great success. He secured the patronage of Charles Talbot, the Duke of Shrewsbury, who gave him the living of Heythrop in Oxfordshire, where the Duke had his country house. Godwyn became Archdeacon of Oxford in 1707 (the occasion for Hearne’s broadside) and then went with Talbot to Ireland in 1713. He was made Bishop of Kilmore in 1715 eventually rising to become Archbishop of Cashel in 1727. He was a moderate in Irish politics and popular with all sides. William King, the Archbishop of Dublin, called him a ‘grave, sober, good man.’

Time though has definitely proved Hearne wrong in his assessment that Godwyn did no good to the College. His first gift of the book of scientific treatises was relatively cheap, a note at the front gives its price as two shillings and six pence, maybe twenty pounds in today’s money. It may have been something he had used in his earlier studies as it bears his name and the rather romantic statement ‘ars longa, vita brevis.’ Perhaps he felt that he no longer needed it with his change in focus or he may have wanted to donate something that reflected the intellectual interests of students at the time (notably the Descartes and Hooke works mentioned earlier were given to the Library in the same period). Whatever his reasons, Godwyn’s gift is now an incredibly important record of the scientific enquiry of the seventeenth century and the volume is also a part of the larger story of the Old Library and the Aularians and others who contributed to it.

Category: Library, Arts & Archives

Author

James

Howarth

James has been St Edmund Hall’s Librarian since May 2018. He is responsible for maintaining and developing the library’s collections – including the historic and special collections that are housed in the seventeenth-century Old Library and is keen to promote their use in research, study and outreach.