Letting the dead rest? Ethical encounters in the archives

12 Mar 2025|Chloë Pieters

- Research

Last summer, while working in an archive in Antwerp, I reached into a case file, opened up an envelope – and pulled out not a letter, but a handful of human hair.

I am a historian of family life during and after the First World War in Belgium and Britain. My current research project uses judicial archives as a key source to investigate wartime life in Antwerp. Belgium was under almost total German occupation during the First World War, apart from a small area in West Flanders. There were a number of occupation authorities, but Antwerp was administered by the Generalgouvernement, under joint military and civilian German authority, in contrast with some areas of Belgium, which were governed under very harsh German military law during the war (the actual details and politics of Generalgouvernement arrangements are quite complicated!).

I use judicial records related to post-war trials against alleged civilian wartime collaborators in two ways. Firstly, as a straightforward investigation of state power, examining how the Belgian state responded to civilian wartime transgressions, such as informing on neighbours, trading with the enemy for profit, or sexual and romantic relationships between Belgian women and German soldiers. Secondly, I interrogate judicial records using a social and cultural historical approach, which effectively means reading the witness statements collected to glean information about daily life in wartime. By reading dozens (and, hopefully, eventually hundreds – there are over 500 cases) of files, I can develop an understanding of how communities and individuals responded to the challenges of war and occupation. I have encountered many large and small dramas of wartime, from women brawling in the street over food rations, to mothers being accused of favouring the Germans for simply instructing their children to greet soldiers politely. There are complicated cases of mistaken identity, with one complex accusation of collaboration hinging on the kind of earrings an alleged informant was wearing.

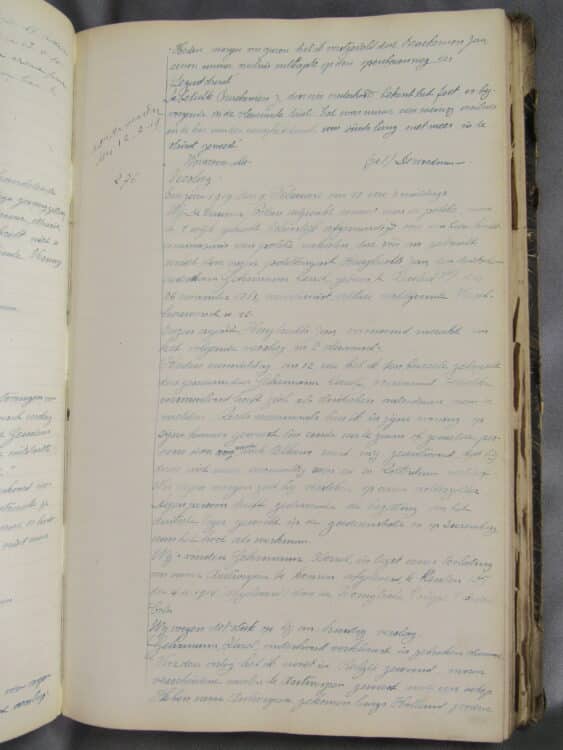

The judicial files and police court records I am looking at probably conform to every stereotype people have about the documents historians work with: they are messy, chaotically organised by long-dead legal clerks and lawyers, often very dirty and dusty (I regularly have to wash my hands throughout the day), and there is a lot of parsing of curly handwriting in much-faded ink and smudgy pencil. Belgian records pose the additional challenge of often being written in both Dutch and French. I have brushed away dust, rust and desiccated spiders in the course of my research (despite the stereotype, archival research isn’t always so literally dusty). They are also quite routine, consisting of similar forms, warrants, witness statements, and so on. When I encountered envelopes full of human hair in one of the folders, it was therefore a terrible shock: accidentally handling parts of a long-dead person’s body, even if only hair, was something completely new and completely unexpected. It turned out to relate to a murder case – the only one of its kind in this archival series – and was part of some of the forensic evidence, alongside photographs, dental records, fingerprints, footprints, and witness statements.

As a historian, encountering the dead is part of my daily professional practice, and as a historian of war I’m familiar with photographs of human beings who have met death in violent ways. Encountering the forensic photographs in these files, however, made me realise that I had never actually seen images of a real person who had died by interpersonal violence. Despite our familiarity with murder from fictional television shows and true crime documentaries, it was moving to see what a frightening and painful end this woman had experienced. In fact, the initial encounter was so shocking that when I took the photographs out of their envelope, I screamed, alarming the archivist.

An archival encounter like this poses problems that neither myself – nor the historical profession as a whole – has entirely resolved. It is not a mystery to be solved by a historical researcher but an incomplete story of a real human being whose complicated life ended in a truly horrific way, and whose afterlife became the subject of a brief transnational police investigation, resulting in her visibility in history.

As one of my other current research projects is on women who were killed by their husbands, I am very preoccupied by the forensic and judicial afterlives of victims and the difficult irony of accessing the lives of ordinary people, who would otherwise have existed outside most written records, because they died in brutal ways, often at the hands of lovers, husbands, and friends. Letting the dead rest is not part of the historian’s mantra, and even the most difficult cases can be insightful and revealing about police practice, social attitudes, lived experiences, and cultural ideas about gender – all the things a social and cultural historian such as myself loves to write about. Still, this goes alongside the sensitivity and care we owe our historical subjects, as we revive them through our accidental encounters with their stories – and sometimes their bodies – in the archives.

Category: Research

Author

Chloë

Pieters

Chloë is the River Farm Foundation Early Career Teaching and Research Fellow in History. Her research focuses on the European family in wartime. She completed her PhD at University College London. Prior to joining St Edmund Hall, she was Stipendiary Lecturer in Modern British and European History at Somerville and Exeter College.