The Hierarchy of Gingerbread: Gift-Giving at Christmas in Medieval Convents

9 Dec 2020|

- Research

As Christmas approaches this year, UK families will have less contact with family and friends. For nuns in medieval Germany who lived in enclosure, a lack of face-to-face contact with people outside of their own convent was entirely normal. Gift giving offered them an innovative strategy of symbolic communication, to remind those beyond the convent wall of their presence.

Across Germany at Christmas in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries nuns would distribute small “monastic gifts”, such as devotional images, rosary beads or something edible. The latter proved particularly popular in the south-west German Cistercian abbey of Günterstal, near Freiburg im Breisgau, where a surviving notebook written by the nuns allows us to reconstruct the distribution of gingerbread or Lebkuchen.

First, the convent had to buy the requisite ingredients for baking. In 1511 the convent’s bursar, Aristoteles, bought ginger, pepper, nutmeg, cinnamon, galangal and saffron from the fair in Freiburg. Such spices were not cheap, and in 1495 a legal case had even been brought to the Freiburg town council that the town’s spice merchants were falsifying their goods; four respected citizens were required to test them.

Once spices had been procured, the nuns set about baking. In 1512 a nun recorded the visit of one Jakob Hässler who came to the convent to teach the nuns a new gingerbread recipe. The nun faithfully recorded how to mix the correct quantities of rye flour, honey and spices. But things did not always go to plan and the scribe noted how the nuns ‘heated the oven as if they wanted to bake white bread. When they had placed the Lebkuchen on trays in the oven they closed the oven door. They should not have done that’. We’ve all been there.

After cooking was complete, the nuns set out making arrangements for the distribution of the baked goods. This was not a simple task as the nuns created a hierarchy of gingerbread based on their weight, colour, shape and packaging. In 1508 men in positions of authority over the nuns, such as the chaplain, received seven pounds of gingerbread coloured with saffron, the most expensive of spices. The vibrant yellow colour and fragrant aroma made clear the object’s status as something to be prized. The next group, including the mayor of Freiburg, received six pounds of uncoloured gingerbread, whilst the next (five and a half pounds) included other women for the first time, such as nearby female convents. The smallest portions were reserved for children, including little Peter (‘Peterli’), the son of the abbey’s bursar in Freiburg, who received ‘small gingerbread’ (‘kleini leppküchli’). Status, gender and age all played a role in what sort of gingerbread you would receive.

What lay behind these gifts? First, the distribution of the gingerbread not only reflected well on the recipients, but also on the abbey itself. It made public the abbey’s ties with the outside world and was a visible sign of the way in which female monastic houses were far from isolated institutions.

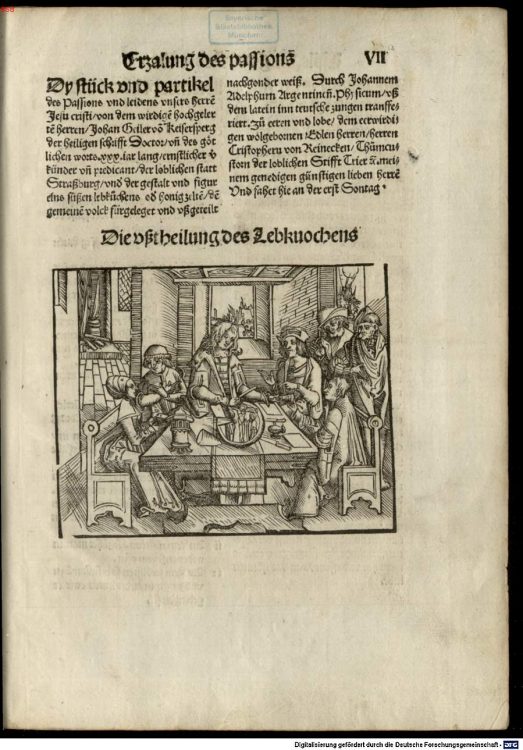

Secondly, the gifts were a sign of friendship. With face-to-face meetings prevented because of enclosure, the gifts took on heightened importance in reminding outsiders of the continual presence of the nuns in their lives. In 1507 Caritas Pirckheimer sent Michael Behaim, Nuremberg’s master-builder, New Year’s greetings and enclosed a small figurine of the Christ child and sugared goods as ‘a sign of our friendship’. Woodcuts such as these, with a ‘Happy New Year’ message and box of sweet goods in the foreground, were widely circulated.

Finally, there were the health benefits, both medicinal and spiritual, of the gingerbread. The Strasbourg preacher Johann Geiler von Kaysersberg’s 1507 sermons ‘Fragments of the Passion of our Lord’ made twenty comparisons of gingerbread baking to Christ’s passion. The cloves added to the mixture were compared to the nails piercing Christ’s side on the cross and the fact that dogs and cats liked to come to smell the mixture whilst it was rising was compared to the presence of the animals in Bethlehem who stuck their noses and mouths into the manger. This was a form of late medieval devotion which evoked all the senses, including touch, taste and smell, and which gave everyday activities spiritual meaning.

Convent gingerbread gives us cause to reflect on where the meaning of gifts comes from. If any members of the Hall discover gingerbread in your pigeonhole this Christmas, please don’t be offended if it isn’t coloured with saffron.

Category: Research