Triptych – our connection to the medieval Hall

20 Nov 2019|Jonathan Yates

- Library, Arts & Archives

The college is fortunate to own a late medieval triptych which, after a number of years hidden from view, has returned to permanent display in the Ante-Chapel. The triptych originates from the southern Netherlands and dates from the 1520s – a fascinating time in European History; only a few years before Martin Luther had posted his 95 Theses. Some branches of the new Protestant faith were opposed to religious imagery and a great many religious works of art in the Low Countries would be destroyed in the mid-16th century. How our triptych survived and came to England is not known. It was given to the college by an Old Member in 1931, having previously belonged to his family, who resided in the north east of England.

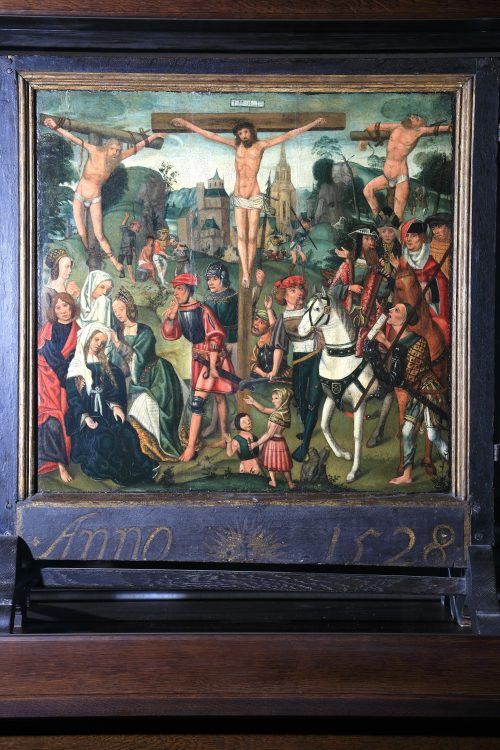

With the doors closed we see the scene of the Annunciation – the angel Gabriel appears before the Virgin Mary. She crosses her arms in acceptance of her role. This was a common theme for the doors of 14th- and early 15th-century northern European triptychs. Through her divine conception Mary enables mankind to experience Christ – she is, quite literally, a door into a world with Christ. During Mass, or during prayer, the doors of the triptych would be open revealing the scene of the Passion. At the centre is Christ on the Cross, wearing the Crown of Thorns, his side pierced. Above his head has been placed a sign with the letters “INRI” – the initials from the Latin for “Jesus of Nazareth, the King of the Jews”. To his right is the repentant thief, whose body leans towards Christ; to the left the unrepentant thief strains away from Christ. In the bottom left John the Baptist supports the weeping Mary surrounded by Mary Magdalene and her friends. In the right are the Pharisees on horseback, richly clothed with quite exotic headgear – the chief Pharisee wears what looks like a mitre. Before them we see the Roman solider Longinus, carrying the spear with which he will pierce Christ’s side, and holding the sign which he will place above Christ. Two children play on a hillock in the foreground of the picture. Unlike the adults, they have no role to play in this scene of the Passion. It might simply be an artist’s device to fill what would otherwise be dead space, and so to preserve the drama and tension in the scene.

The donors who commissioned the triptych appear on the left and right panels. The donor is to the left with St Christopher. There are three living sons, and two, shown in smaller stature, who have died. The donatrix is to the right with Mary Magdalene (shown with her jar of ointment). She has seven living daughters, and three that have died. The donors belong to the same world as the central scene, the landscape behind connects them to the central panel. They appear to be within a building, perhaps a church. They encourage us to follow their example, and join them in prayer before this scene of Christ’s suffering.

In 1913 the German art historian Max Friendlander identified a small number of paintings as belonging to an artist he named the Master of Delft. The Master’s chief work is the magnificent crucifixion triptych in the National Gallery. Although it is much smaller, our triptych has similarities with the National Gallery triptych. Two children playing is a common element in paintings associated with the Master of Delft. However, there is a more striking comparison with a second work held in the Wallraf-Richatz museum in Cologne. Our triptych has such strong compositional similarities with those in the National Gallery and Cologne that it must be a product of the same workshop. However, the hand which painted our triptych could not have been the Master responsible for the work in the National Gallery.

Although the site of our college has been connected with teaching and scholarship for most of the last millennium, much of what we see around us is relatively modern. This triptych connects us with the medieval origins of our Hall, transporting us to a time before the Reformation.

Category: Library, Arts & Archives

Author

Jonathan

Yates

Professor Jonathan Yates is a tutor in Materials Science at St Edmund Hall. He also holds the role of Picture and Chattels Fellow which sees him take responsibility for the cataloguing, conservation and use of the Hall’s art collection, including paintings, photographs, silver and other items.