‘Bought out of Mr Churchill’s study’: John Mill, the Old Library and the Churchill Family

14 Feb 2023|James Howarth

- Library, Arts & Archives

The ‘New Leiger [i.e. Ledger] Book’ book begun by Stephen Penton in 1676 is the oldest surviving record of the Hall still in College Hands. Glimpses of the history and development of the Old Library occur frequently in its early entries. For example it records expenditures on books, their bindings and for the chains that attached them to the shelves, receipts signed the various craftsmen involved in the building of the Chapel and the Library as well as the payment of £1 to Thomas Hearne for “transcribing the… catalogues of the Library.”

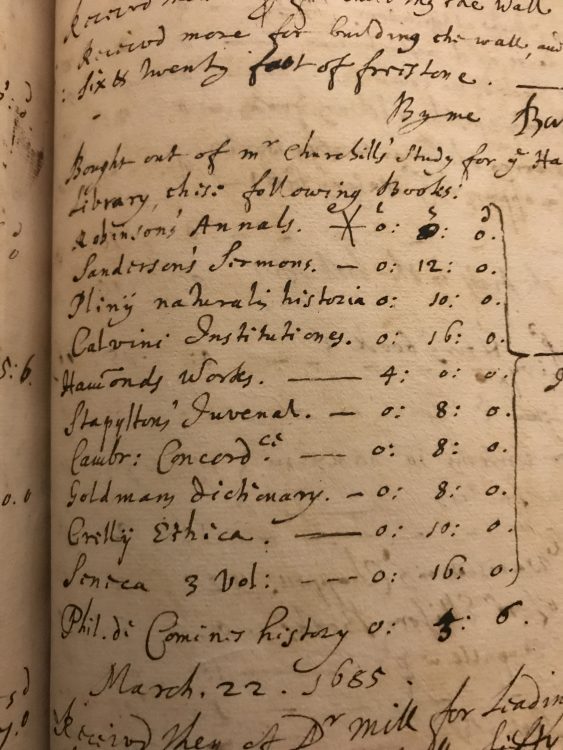

One such entry is rather mysterious, a list of eleven books (with prices) headed: “Bought out of mr Churchill’s Study for ye Hall Library, these following books:”

The entry can be dated by the preceding and succeeding entries to sometime between the 11 and 22 of March 1686. (nb the text reads 1685 but that is taking the beginning of the year to be 25 of March, the beginning of the legal and tax year, not 1 January). The list appears amongst several receipts for building works and other expenses so does appear to be ‘bought’ (as in ‘purchased’) rather than ‘brought’ (as in ‘moved’).

No-one of the name of Churchill is known to have matriculated at the Hall around this date and the records from the Buttery Books do not start until 1694. Nine of the eleven books remain in the Old Library but none of them have any marks of ownership or donation and there is no entry for Churchill in the Benefactor’s Book (unsurprising if the books were paid for not a gift).

So, who was the mysterious ‘Mr Churchill’ and why was he living in Hall in 1685?

The Likely Candidate: Theobald Churchill

The key to Churchill’s probable identity can be found in Thomas Hearne’s draft catalogue of the Old Library which is now in the Bodleian (MS Rawlinson C851). Entries list books in shelf mark order with author, title, publication details. Sometimes Hearne has also written marginal notes identifying the books donor.

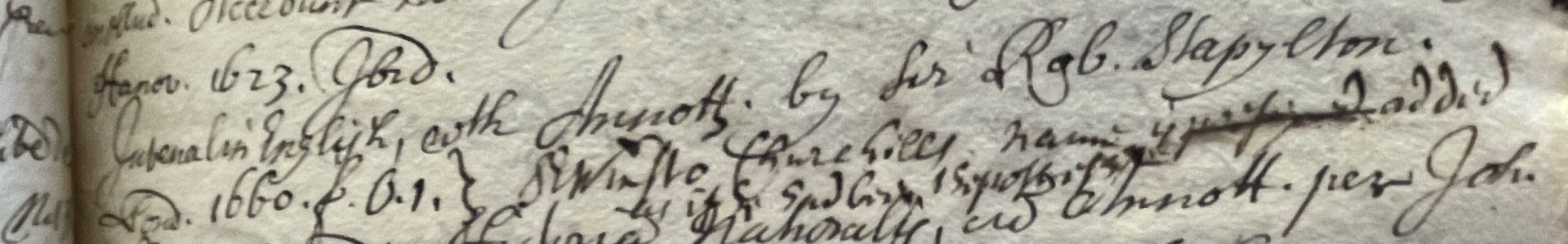

Against Fol. O 1, which is a copy of Juvenal’s Satires from the Ledger book list is written: “Sir Winstō Churchills name is added as it had been his possession”

Sir Winston Churchill (1620-1688) was the father of six children including John Churchill, the Duke of Marlborough and victor at the battle of Blenheim and Arabella Churchill who was the mistress of James II, bearing him four children. His youngest son Theobald was a student at Queen’s (mat. 1677, aged 14) and it is with him that we can find a link to Teddy Hall.

Theobald’s tutor at Queen’s was John Mill, subsequently Principal of the Hall from 1685 until his death in 1704, as recorded by the historian Anthony Wood in his account of a tour of Oxford in 1683 by the Duke of York (the future James II) and his daughter Anne:

“From Magd. Coll. they went in their coach to Queen’s Coll., where the provost, fellows, and all the rest of that College being in their formalities, they were by them received in the quadrangle between the gate and the chappell dore, and had a speech in Latin and a copie of English verses — made by his tutour. Dr. John Mill — spoken to them by Theobald Churchill, B. of A. of that college, son of Sir Winston Churchill, and yonger brother to (John) Churchill lately created a Scotch baron (of Aymouth) by his majestie.”

Theobald was destined by his family for a career in the Church. He graduated with an MA in 1683 and was ordained a Deacon by John Fell, the Bishop of Oxford, on 13 December 1693 and a priest in September 1684. Upon graduating he seems to have immediately been seeking preferment. He was commissioned a Chaplain in the King’s Own Royal Regiment of Dragoons – his brother’s regiment – in November 1683; this was by way of being a sinecure as the regiment was not in active service at the time. The following year he received a mandate from Charles II for a Fellowship at Eton, but was frustrated as an election had already been made when the document arrived. At this point however his career was cut short as he died (of consumption Hearne reports in his diary) in London on 3 December 1685 before he could receive “some great Preferment wch was design’d for him.”

It seems very likely that Churchill had continued studying with Mill after his graduation and briefly moved with him to St Edmund Hall in the autumn of 1685. There is at least of one other case of Mill offering a programme of advanced theological studies to a student after their graduation so as to increase their chances of preferment in the Church.

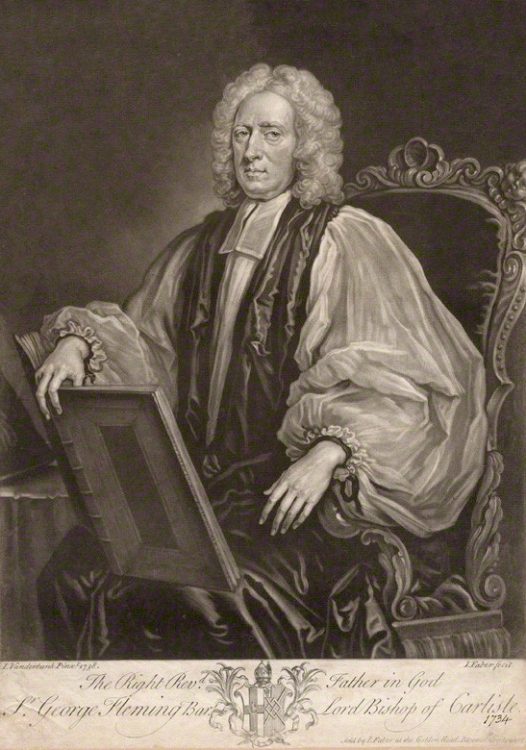

A parallel case: George Fleming

George Fleming (mat. 1688) was not supposed to be at Teddy Hall. His Father, Sir Daniel Fleming and three of his brothers were all students at Queen’s. George arrived in Oxford in the summer of 1688 bearing letters of introduction from his father to both Timothy Halton, Provost of Queen’s, and in case of his absence, John Mill Halton was on business in Wales, so George ended up a student at the Hall.

A large correspondence exists between Sir Daniel Fleming, his sons and also the various academics who taught them in Oxford. George flourished under Mill, who wrote to George’s father: “I never met with a youth of greater diligence and Discretion, constant at his exercises, his meals, his Prayers ; obligeing and belov’d by every body.”

George remained studying a carefully constructed programme of Divinity under Mill after he graduated MA, indeed he remained in Oxford not only after his ordination in 1694 but even after he was made Vicar of Aspatria in Cumbria in 1695. Shortly after George had completed his BA studies, Sir Daniel wrote to Mill:

“After that he hath taken his Degree I shall begg ye continuance of your kindness unto him in favouring him with your directions in his Future Studies, especially in Divinity. And the sooner yt he shall enter into Orders I think it will be ye better: For then he will apply himselfe more closely to ye Study of Divinity & he will then be more capable of Preferment”

Mill provided pastoral as well as academic support during George’s protracted stay in Hall. The Principal dealt with a crisis shortly before George’s ordination when he was struck with sudden doubts and a hankering for a more exciting (and expensive) career at court or as a lawyer. He also gently dissuaded him from taking a chaplaincy in the East India Company and wait for more secure preferment. It should be noted that this is not entirely altruistic on Mill’s part; by persuading his proteges to remain in Oxford under his instruction, he was not only aiding their future careers but also continuing to receive their fess. However, in George Fleming’s case at least the study paid off: he returned north to become Chaplain to the Bishop of Carlisle in 1697, became a Canon of the Cathedral in 1701, Archdeacon in 1705 and ultimately Bishop in 1735.

Theobald Churchill and his father would have hoped for a similar and perhaps – given his family connections and rising fortunes – more meteoric career. It is easy to see why they might have chosen the continued educational guidance and firm guardianship of Principal Mill.

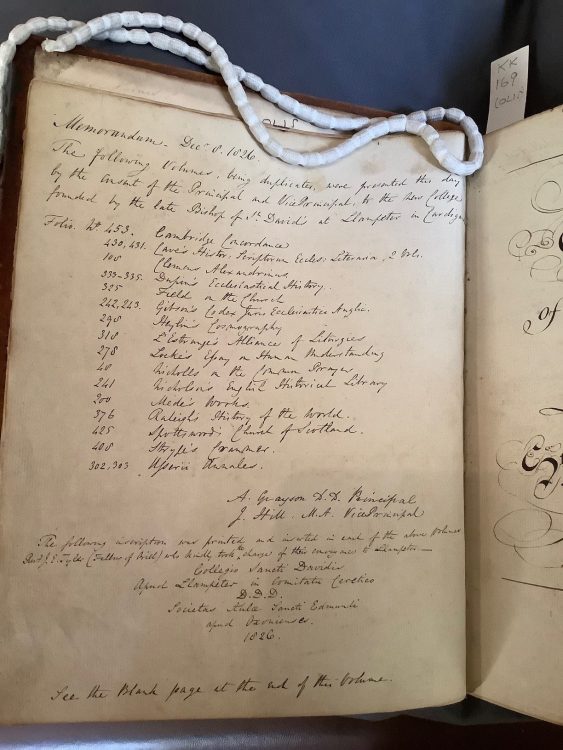

‘For the Hall Library’: The books

As previously mentioned, nine of the books on the Ledger Book list remain in the Old Library. The two that are gone are reference works which may have been removed after they were superseded by later books. One, A concordance to the Holy Scriptures by Samuel Newman (Cambridge, 1682, shelfmark was Fol. N 6) was amongst sixteen books given by the College to the newly established St David’s College in Lampeter in 1826. The other was A copious dictionary: in three parts by Francis Gouldman (London, 1669, shelfmark was 4o R 8), this was still in the Library in 1774 but had disappeared by the time a new catalogue was made in 1792.

Another on the list, Hugh Robinson’s Annalium mundi universalium (London, 1677, Shelfmark Fol. G 12) is asterisked and has had its value changed to zero. This seems to be because it was in fact the Library’s existing copy which Churchill had borrowed (and so wasn’t part of the ‘donation’). This shows that although the construction of the Old Library was almost complete, the chaining of books had not yet begun and scholars were free to take books to their rooms (as had been the practice under Thomas Tullie before the Library project had begun). The Ledger Book in fact doesn’t contain entries for the purchase of book chains until 1694-5. The book was one of a number of reference works written by Robinson for pupils at Winchester College where he was chief master, it provides a chronology of events in the Bible from Creation to Nebuchadnezzar’s taking of Jerusalem. It is one of four books donated by Aularian Edward Worsley (mat. 1676) , perhaps after his graduation as an MA in 1682.

As might be expected theological works form the largest grouping of texts in the list. There is John Calvin’s fundamental doctrinal work Institutes of the Christian Religion (Institutio Christianae Religionis, Amsterdam, 1667, Shelfmark Fol. E 14), one of the key texts of the Protestant reformation. A sheet of handwritten notes inserted into volume show it was still in use for regular study in the late 19th century.

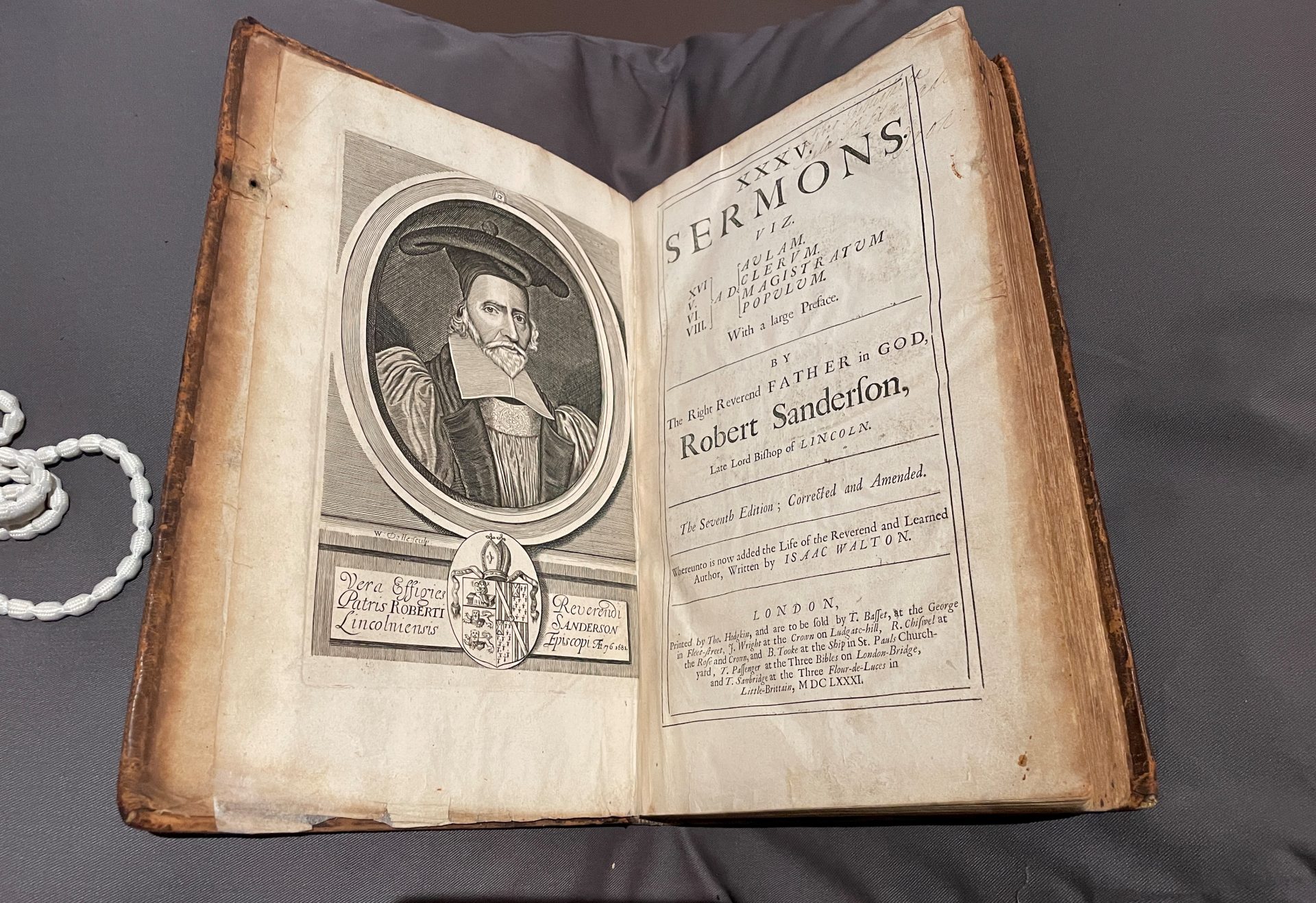

Other works reflect the via media of the post-Restoration Church of England as one might expect for an ambitious clergyman in training. They include Richard Sanderson’s Sermons (London, 1681, Shelfmark Fol. G 6); Sanderson, who was Bishop of Lincoln, was doctrinally low church but of impeccable Royalist credentials and his sermons were renowned as a model of preaching. There is also the Works (London, 1674-1684, shelfmarks Fol. A 12-13, B 1-2) of Henry Hammond. Hammond was equally Royalist but much higher church in his outlook, a staunch defender of the episcopacy and the liturgical tradition of the Church during the Commonwealth.

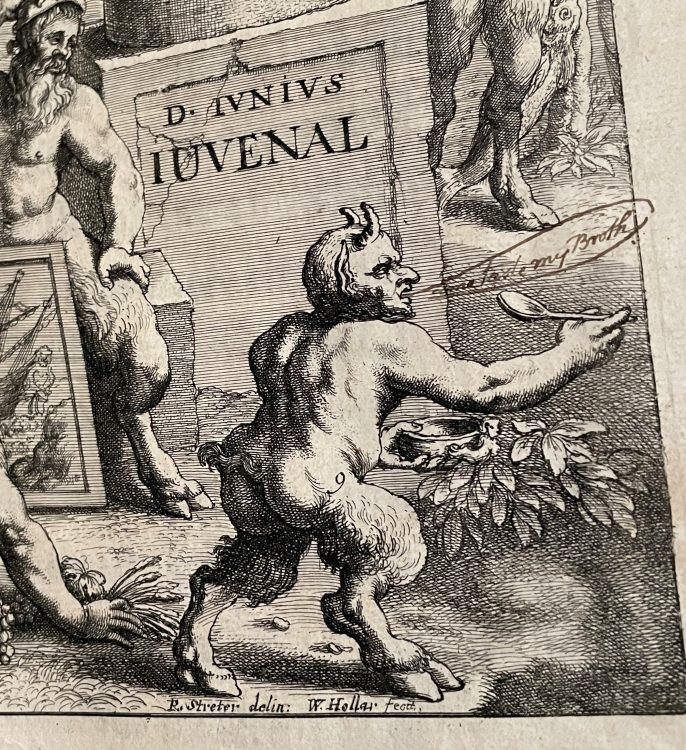

Classical texts are also well represented. Perhaps the most attractive book on the list is a large folio translation of Juvenal’s Satires (London, 1660, Fol. O 1) with a gold leaf decorated on the spine and book edges and with an engraved title page showing the author and a group of satyrs. Particularly charming is that someone (perhaps even Churchill himself) has drawn a speech bubble saying “Come taste my broth” coming from the mouth of a small satyr with a spoon.

There are also copies of the Works of Seneca (Amsterdam, 1671, 4° B 11-13) and of Pliny’s Natural History (Lyon, 1553, Fol. O 2). These texts were not just for literary study; as Natasha Bailey notes in this year’s Hall Magazine, Mill used references to Classical Literature to explicate passages in his lectures on the Bible:

“He taught students to interpret Ezra 6.11 as referring not, as in the King James Bible, to a man being hanged from timber, but to his being impaled on a stake. As Mill pointed out, such a punishment “was (& is) a custom much used by the Eastern nations, & likewise by the Romans, & is remembered by Juvenal &c”. The last comment is also a helpful reminder that it was often via reading classical poetry that early modern scholars such as Mill gleaned insights into sacred history.”

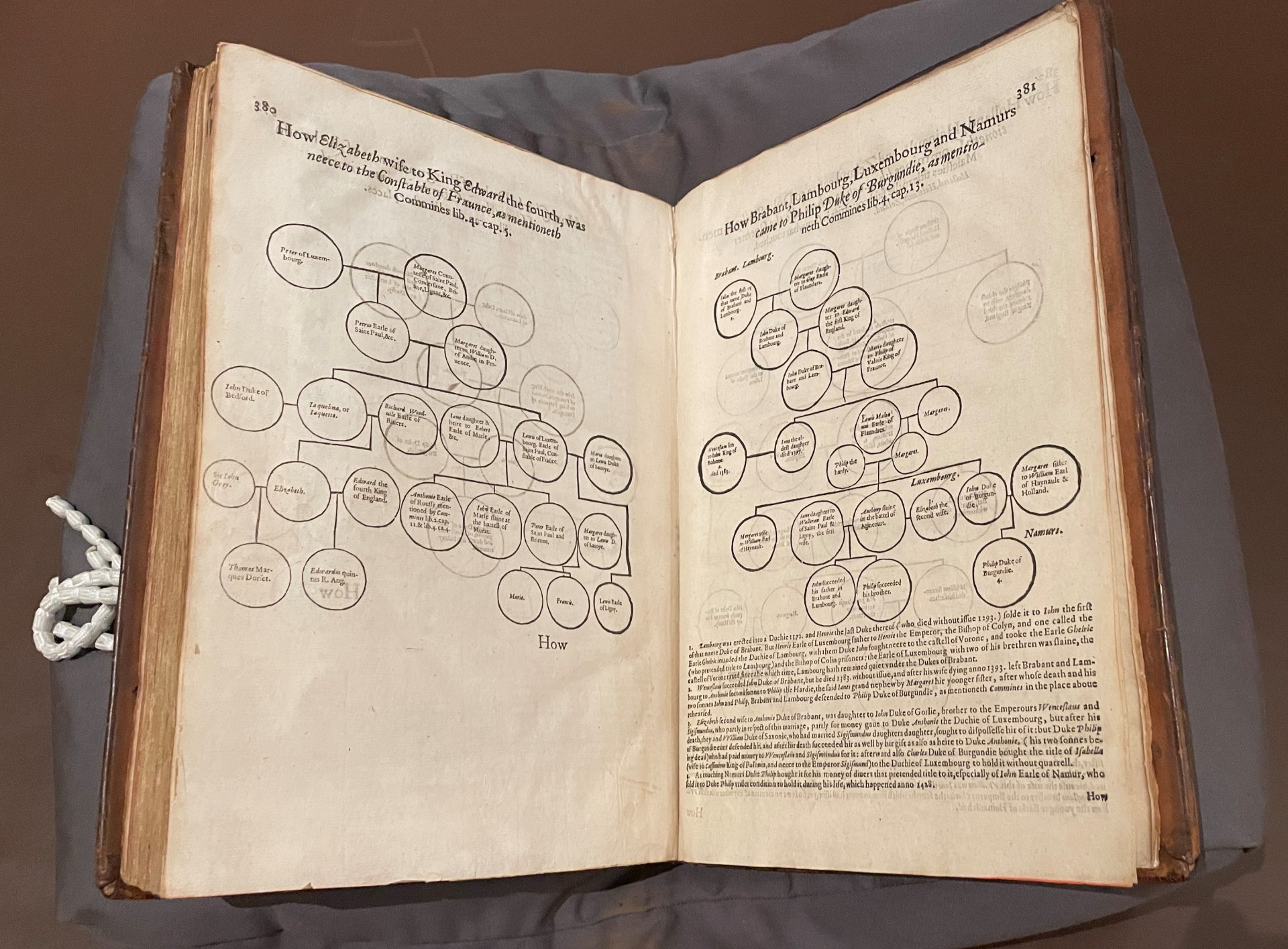

It is striking that the majority of the books were relatively newly published: nine of the eleven were published after 1660 and three in the 1680s (one as late as in 1684). Only two of the volumes were printed before 1600, the Pliny (1553) and a copy of The historie of Philip de Commines Knight, Lord of Argenton (London, 1596, Fol. G 11), a history of late 15th century Europe illustrated with complex genealogical tables. George Fleming provides another potential illustrative parallel here, he and his brothers bought many books to university from their father’s extensive library but also purchased new books in Oxford. Mill may well have focussed his choice of titles the newest title from the books in Churchill’s study.

Uncertainties remain about the nature of the list, particularly given Thomas Hearne’s concerns about Mill’s handling of the donations of Francis Cherry and Henry Partridge which are similarly listed in the Ledger Book.

Occasional book purchases are recorded in the Ledger Book, but the £8 pound and 8 shillings total in the Churchill list would be the largest single payment for books that isn’t underwritten by a gift (as with the Cherry and Partridge donations). It is very tempting to imagine that the outlay was only notional and that no money changed hands, i.e. that the books were a donation. Against that there is no entry in the Benefactor’s Book, nor, despite the note in Hearne’s catalogue, was Winston Churchill’s name ever added to any of the volumes. The removal also took place three months after Churchill’s death – had it taken that long for word to reach Oxford? Did Mill have permission to take/purchase the books or did he act on his own initiative? Did they offset battels owed to the Hall?

It seems unlikely they represent the entirety of the books Theobald Churchill would have possessed in his study. When Henry Fleming left Queen’s to take up the living at Grasmere in 1689 he passed on 68 books to his younger brother George (Sir Daniel Fleming demanded strict accounting of all the books in his son’s possession as they were mostly from the family library so the Fleming’s correspondence contains many lists of books). In the Churchill list, the Commines volume is written slightly later than the main list, Mill perhaps had settled on taking a round figure of ten books and the Commines was added after he noticed that Annalium mundi was already a Hall possession.

Postscript: John Mill at Blenheim Palace

Theobald Churchill’s death was not the end of Mill’s acquaintance with the Churchills, although their next encounter ended on a rather bathetic note. Twenty years later, Thomas Hearne records a rather malicious anecdote in his diary. In January 1706, the Duke and Duchess of Marlborough visited Oxfordshire to inspect the construction work at Blenheim. A group of pro-Whig heads of houses, including Mill, planned to visit and pay their respects at a grand levée the Duke was holding.

Mill decided to steal a march of the rest of the party, left the night before for his parish of Bletchingdon so he wouldn’t be missed and then next morning borrowed two horses and hurried to Woodstock. He proudly announced himself as “Tutor some years ago to his Youngest Brother, who was Commoner of Queen’s Col.” to the Duke’s apparent complete indifference.

At this point the rest of the party arrived. The Duke and Duchess who had been expecting an official delegation from the University, were distinctly unimpressed by what they disparagingly called ‘a body of divinity’ and received them “after a slight manner.” The mortified dons were packed off with half a dozen bottles of wine to “a Little Inne in Woodstoock where they were… slenderly accommodated… [with ] this poor entertainment.” They ended the day back in Oxford, where the Provost of Oriel, George Royse (originally an Aularian, mat. 1671) attemped to raise their spirits with dinner in his lodgings. Ten books worth £8 and 8 shillings seem a small price to pay in comparison.

Category: Library, Arts & Archives

Author

James

Howarth

James has been St Edmund Hall’s Librarian since May 2018. He is responsible for maintaining and developing the library’s collections – including the historic and special collections that are housed in the seventeenth-century Old Library and is keen to promote their use in research, study and outreach.