‘For books in the Library’ or the uncertain fate of £10: An account of donations by Francis Cherry and Henry Partridge

16 Jun 2021|James Howarth

- Library, Arts & Archives

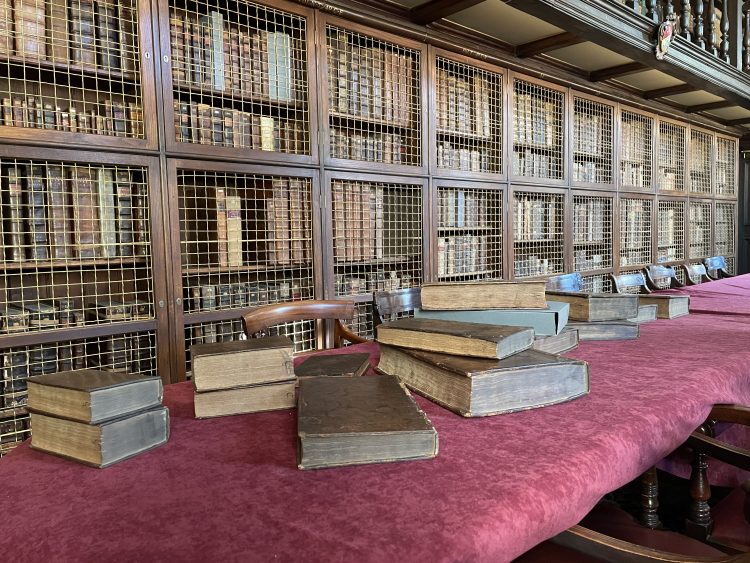

The collections in both the Old Library and the modern Library in St Peter-in-the East are built upon the generosity of generations of Aularians. Indeed, books and donations, were given from the late 1665s before we even had a Library to house them in. We continue today to receive very welcome gifts of books and donations with which to purchase them.

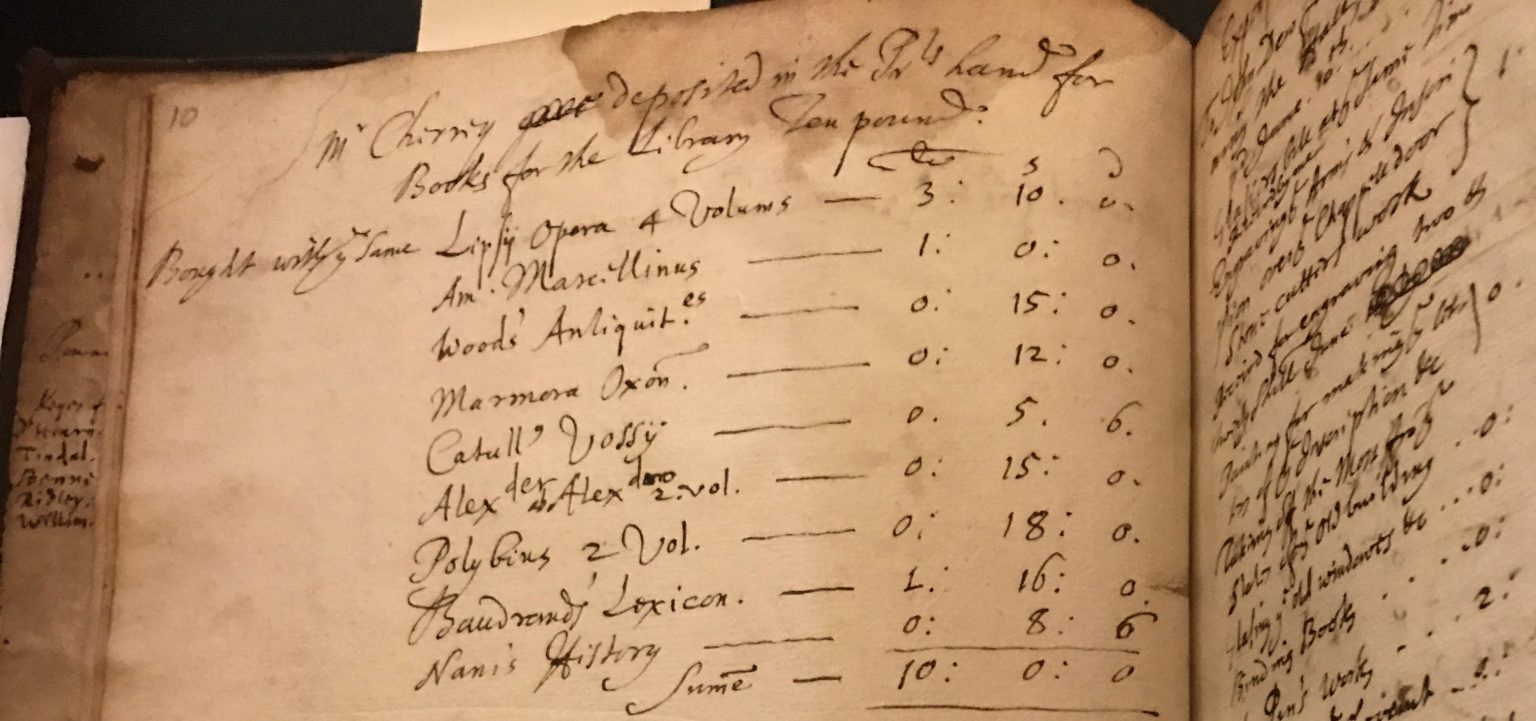

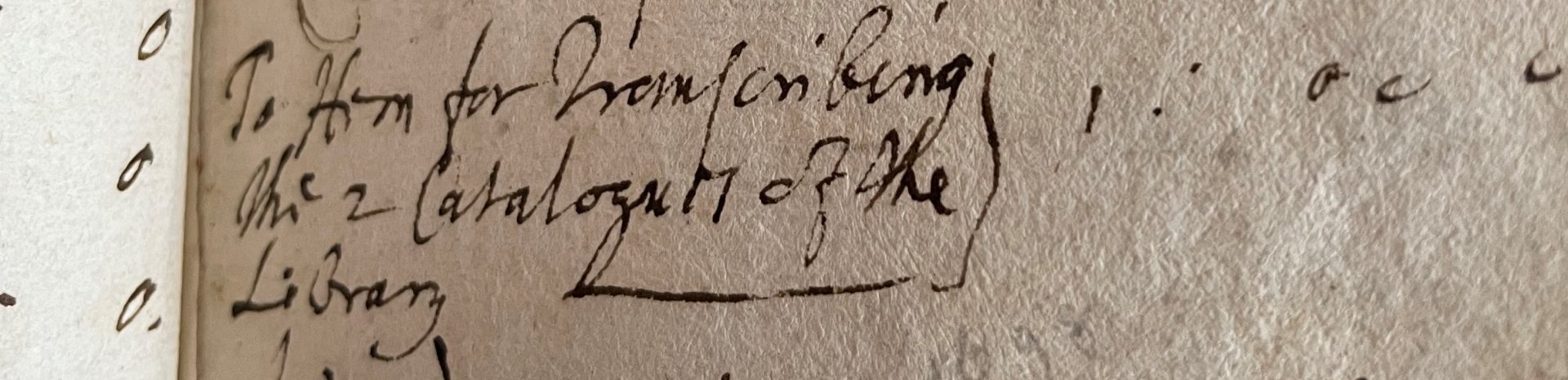

The details of two such gifts from the 1690’s can be found in the oldest record which still belongs to the Hall, the ‘New Leiger (i.e. Ledger) Book’ started by Stephen Penton (Principal, 1675-1684) and used until the nineteenth century.

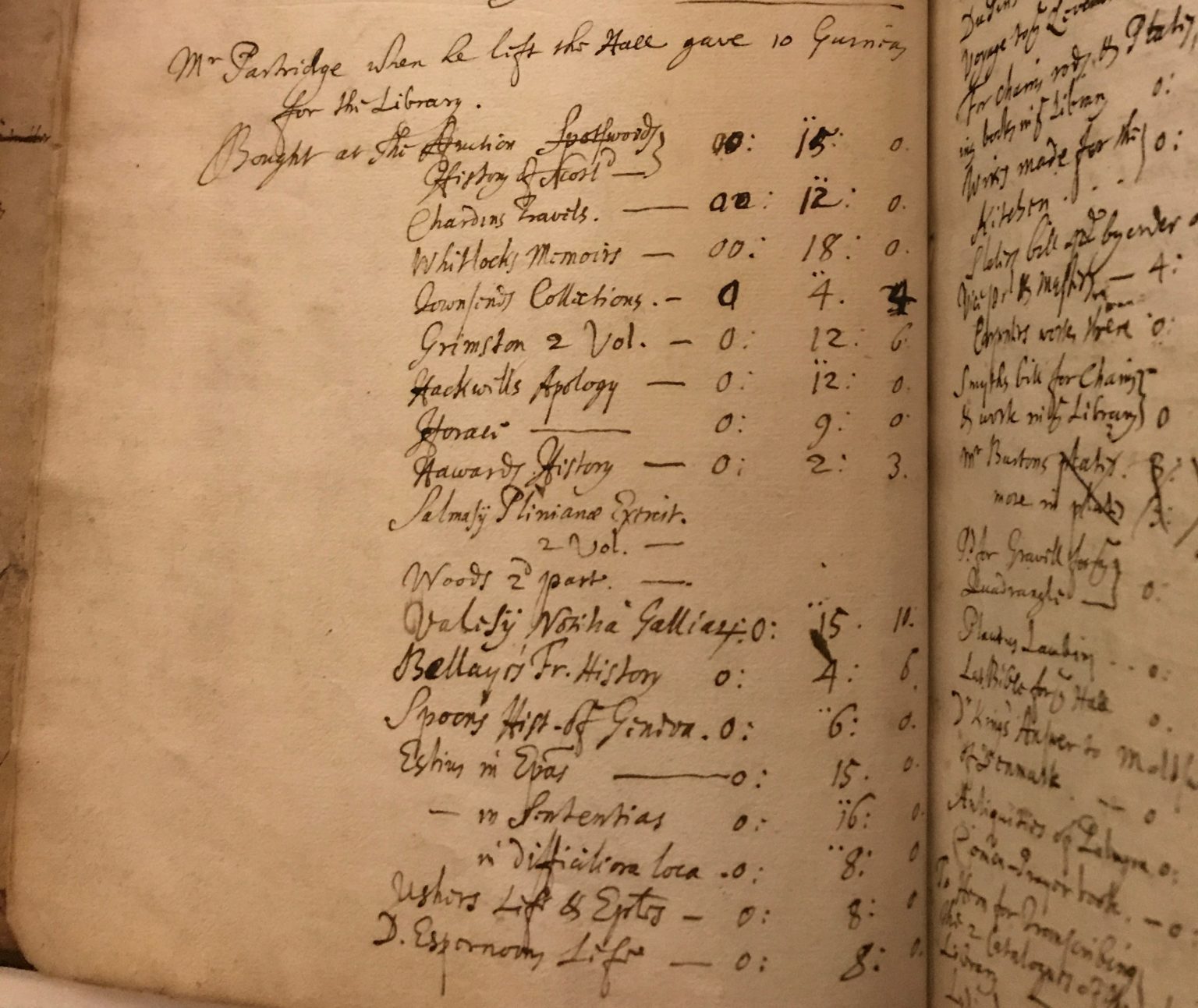

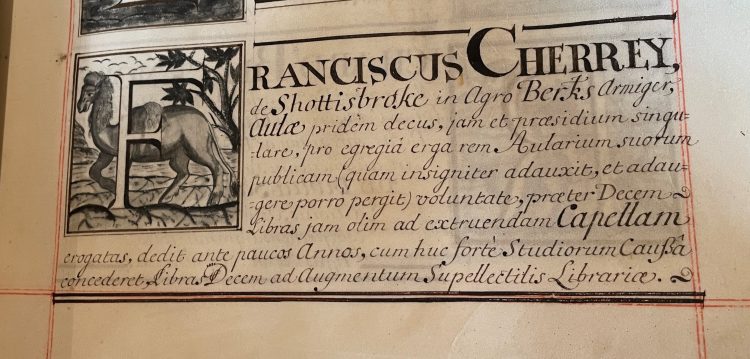

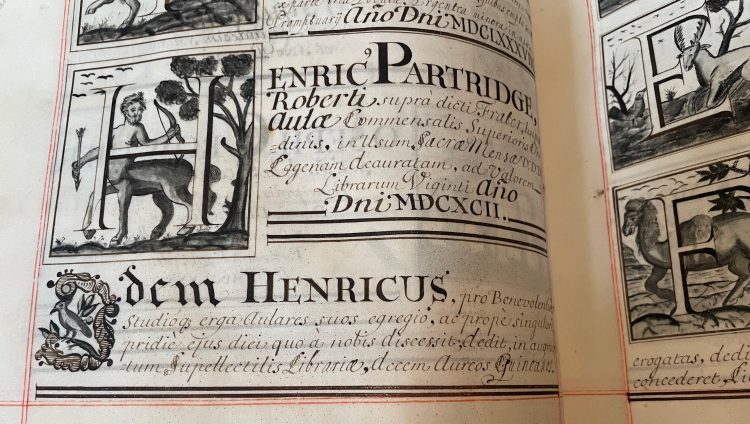

One page records the two gifts of £10 given in around 1693 by Aularians Francis Cherry (mat. 1682) and Henry Partridge (mat. 1688) and details of the books and their prices that were purchased with the gifts. The amount given was not insubstantial, £10 is the equivalent to at least £1400 and maybe slightly more than £20,000 in relative value compared to today. Both Cherry and Partridge had also previously donated towards the cost of the construction of the Library and Chapel. Cherry gave £10 and Partridge a silver flagon for the communion table in the Chapel worth £20 (his older brother Robert [mat.1686] also gave £15 for the wainscotting in the Chapel).

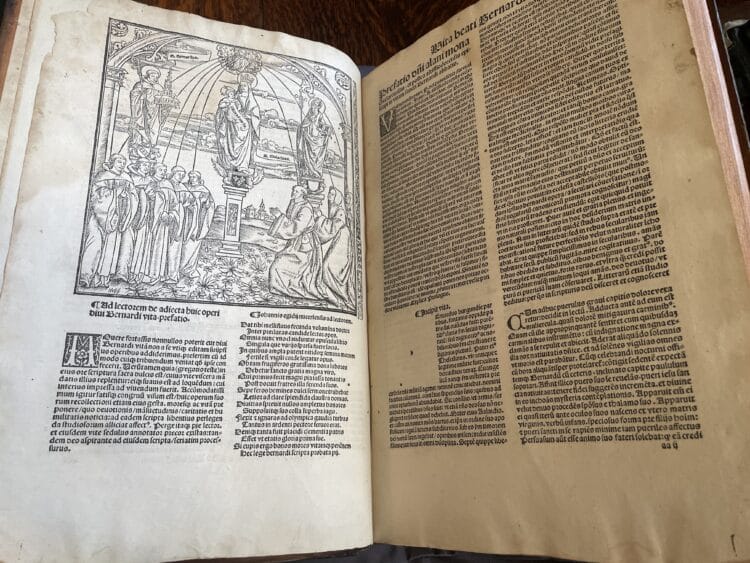

The 26 purchased books cover a variety of topics, but all would be useful for undergraduate teaching in the Hall. They are mostly also relatively ‘modern’ books as well; 15 of them were published after 1670 so were only 20 years old. Only two books were published before 1500.

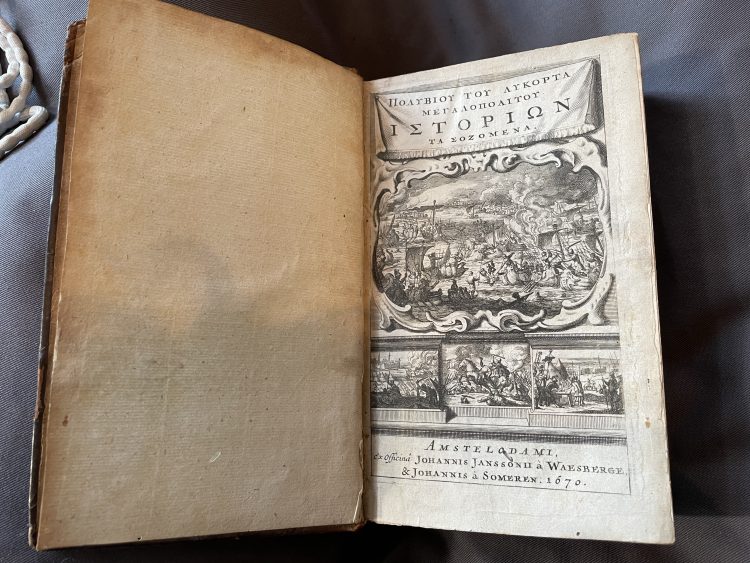

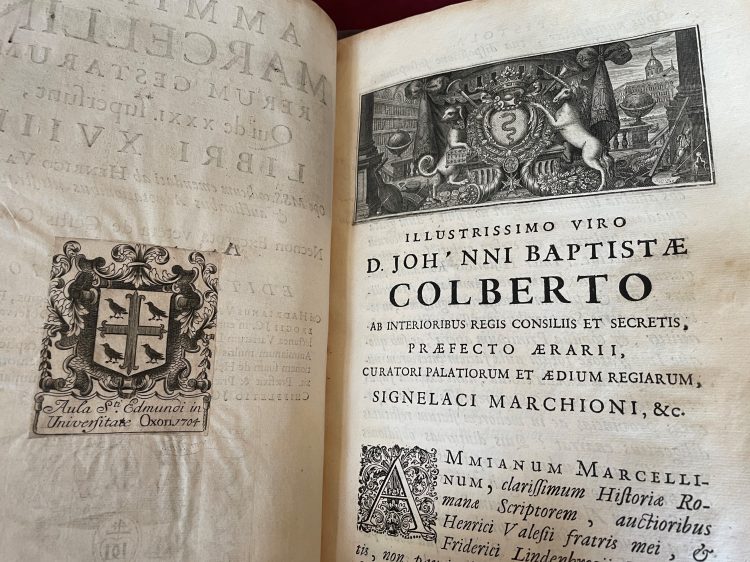

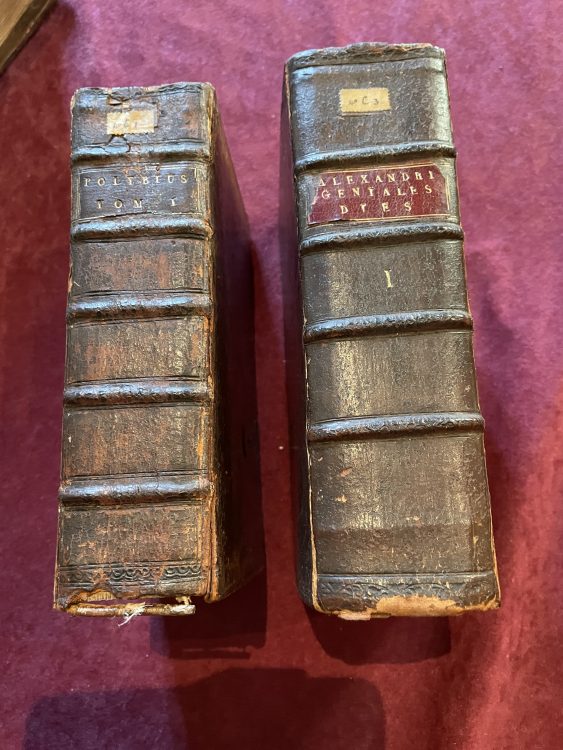

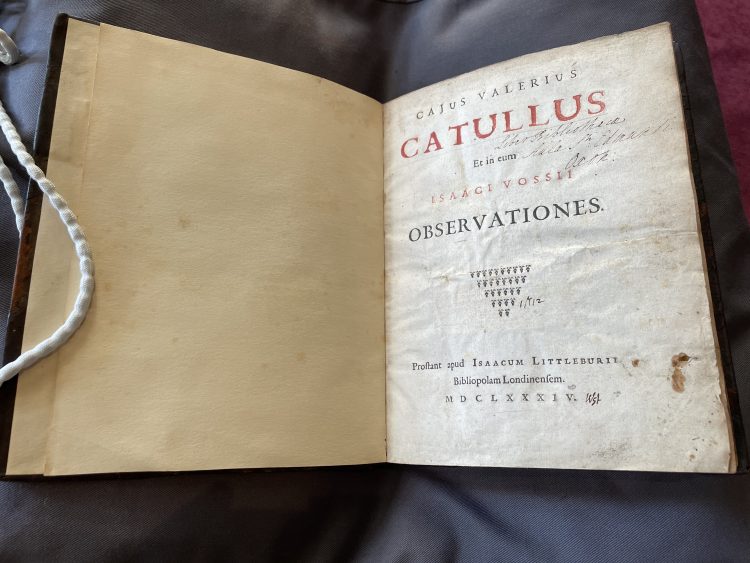

There are works by classical authors, such as the historians Polybius and Ammianus Marcellinus , the poets Horace and Catullus, and the naturalist Pliny the Elder. All of these are working, academic editions with commentaries and notes from contemporary 16th and 17th century writers.

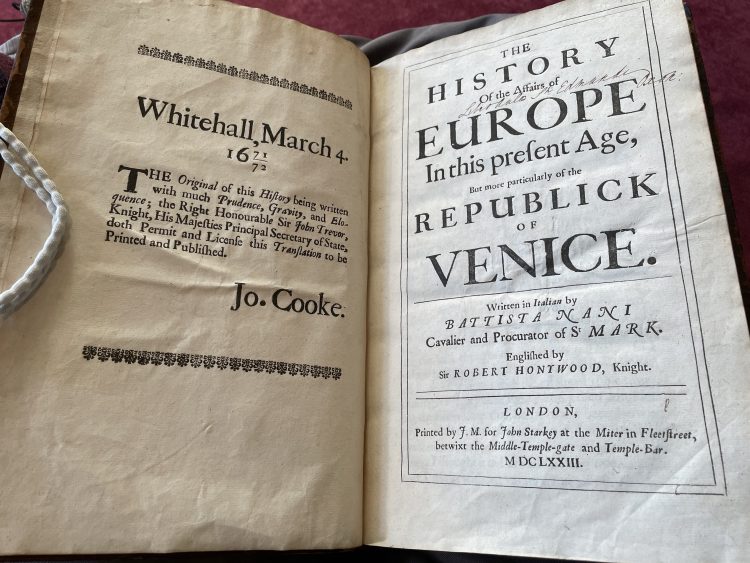

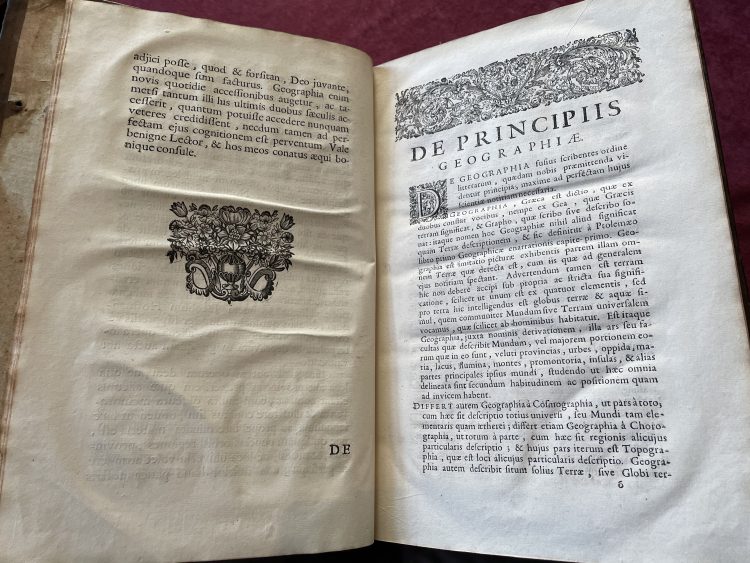

There are a number of works of contemporary history including Jacob Spon’s History of the city and state of Geneva, from its first foundation to this present time and The history of the affairs of Europe in this present age, but more particularly of the republick of Venice by Giovan Battista Nani. Other volumes include legal commentary by the Renaissance Alexander ab Alexandro, commentary on the Epistles of St Paul by the Dutch theologian Willem Hessels van Est and the Geographical gazetteer and lexicon of Michel-Antoine Baudrand.

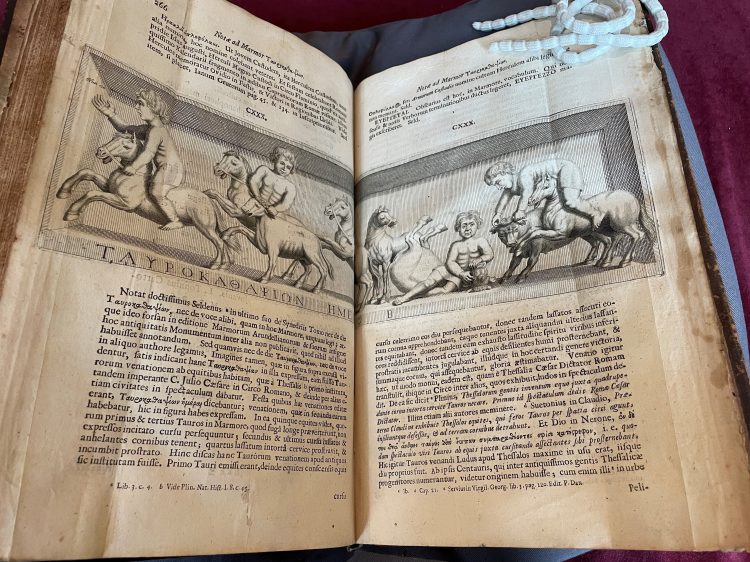

There are also a number of books on the history of the University including the copy of Anthony Wood’s Historia et antiquitates Universitatis Oxoniensis which afterwards became the site of a dispute in its margins about the original name of the Hall. There is also the lavishly illustrated Marmora Oxoniensia which catalogues the Arundel marbles collection in the Ashmolean.

Remarkably, all ten of the works bought with Cherry’s money and all but four of the 16 books bought by Partridge remain in the Old Library. Although neither donation is recorded in any of the books, their shelfmarks can in most cases be identified with the earliest catalogues of the Library and many have the Hall’s original 1704 bookplate confirming them to have been in place since at least then.

One of the missing Partridge books, The history of the church and state of Scotland by John Spottiswoode, was in the Library until 1826 when it was donated along with 15 other books to the newly founded College of St David in Lampeter, where it remains. Two more are in the 17th century catalogues of the Old Library but have vanished by 1792 when a new catalogue was produced. The missing copy of The Travels of Sir John Chardin by the French explorer Jean Chardin is more mysterious as it doesn’t appear in an extant Library catalogue.

In general, the surviving volumes are rather plainly bound with some stamped decorations on the spines and covers, although the Marmora has traces of a more elaborate decoration on its front. Just the fact that we still possess the books and know something of their past is exciting but their part in the history of the Library turns out o be more complicated than it seems

“Which he naver layd out in books” Enter Thomas Hearne with a scandalous report

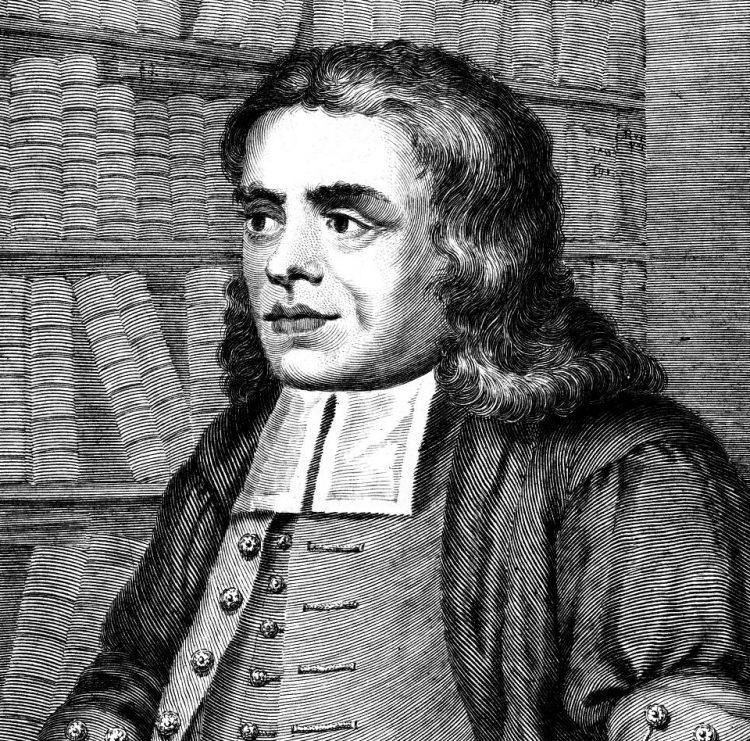

So far this seems a simple story of Aularian generosity and of the remarkable survival of much of the Hall’s earliest collection of Library books. However, as is often true in this period, a more complicated situation is revealed in the diaries of Thomas Hearne (mat. 1696).

He records that 1707 he was approached by William Bickford with a question (mat.1702 of Dunsland in Devon, Hearne elsewhere call’s him ‘the Honour of Edmund Hall’ ):

“M’. Bickford, commoner of Edm. Hall, when he was about to leave us came to me and ask’d me whether, since he design’d to be a Benefactor to ye Hall Library, it were better to buy a Book himself, & see it put in before he went, or put 20 shillings into ye Principal, Dr. Mill’s Hands, to be layd out in a Book by him.”

Hearne responded with an accusation of perfidy on the part of the Principal John Mill (Principal 1685-1707):

“I advis’d him to buy a Book himself, because I could give several Instances of Money being lodg’d in D’. Mill’s hands, which he never layd out in Books, or at least if he ever did buy any Books (which however he very seldom did) he put extravagant Prices upon them.”

It quickly becomes clear that Hearne has the use of Francis Cherry’s £10 in mind as the main example of this. The cost of Baudrand’s Geography for example Mill claimed to be 30 shillings (actually £1 16s or 36 shillings in the list in the Ledger Book) whereas “the Price is well known to be but 15 [shillings]. and dear at yt.” Moreover, he goes on, in some cases Mill simply removed books from his own study and placed them in the Library, while ascribing them ‘Great rates’ (i.e. high prices) in the accounts.

Bickford was unconvinced and duly handed over his 20 shillings to Vice Principal Musson, but “no Book bought wth it from that day to this.”

Hearne’s anger over the way he felt the donation from Cherry had been used was understandable. Cherry was both a friend and a benefactor, he had paid for Hearne’s schooling and his place at the Hall. However, is there any substance to his accusations?

Other evidence of the donation: The Hall’s Book of Benefactors

Elsewhere Hearne complains that in the early 1700s there “a strange neglect” to record the names of donors in the Hall’s sumptuous benefactors book, “that has given much offense to several Gentlemen that were otherwise inclined to be Benefactors.”

This is not the case with the Cherry and Partridge donations whatever else may be true of them. Although there is nothing referring to either donor in the book themselves they both are celebrated in the Benefactor’s book, as well as the entries in Hearne’s catalogue.

The entry for Partridge which is appended to an earlier donation of a silver flagon for the chapel, also has the detail that his donation was made out of his ‘singular zeal for members of the Hall’ and was made on the day he went down from the University.

“He put extravagant Prices upon them”: The price of the books

It has to be said that the prices ascribed to the books in the two lists in the Ledger Book do at first glance seem to be rather high. Three of the nine titles on the list of books funded by Cherry cost more than a pound. Of the 26 titles across both lists 16 cost more than 10 shillings and only three were under five shillings.

By comparison, in a list of more than 50 books belonging to Aularian undergraduate George Fleming (mat. 1688), which he sent to his Father as part of his accounts, none are valued at £1 or more. The Balliol Fellow, Nicholas Crouch, routinely recorded the price of his book purchases in his papers and in the book themselves for nearly 40 years before his death in 1690 and he only paid more than £1 for a book on three occasions.

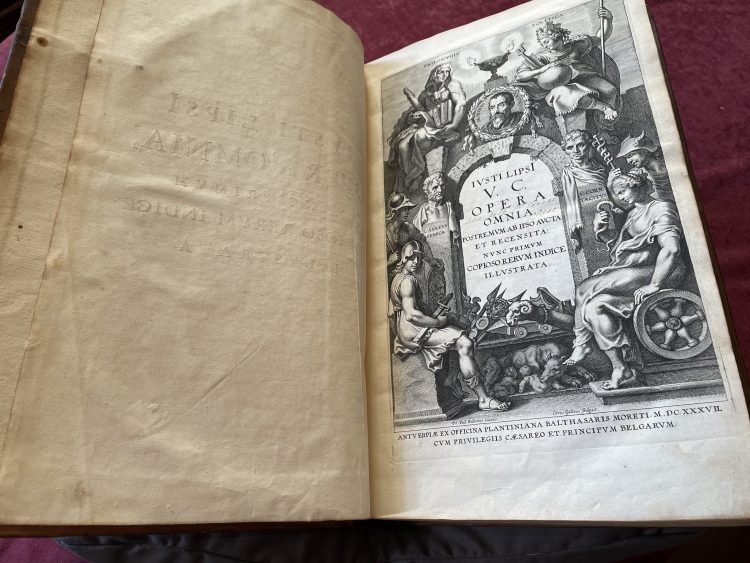

On the other hand, all but four of the books on the lists are large folio volumes, more expensive than smaller octavo, quarto and duodecimo books. Also, only one of the titles costing more than a pound is a single volume work, the Res Gestae by Ammianus Marcellinus. The most expensive purchase, the works of the Flemish philosopher Justus Lipsius (Joest Lips) may have cost £3:10 but consists of 4 substantial illustrated volumes.

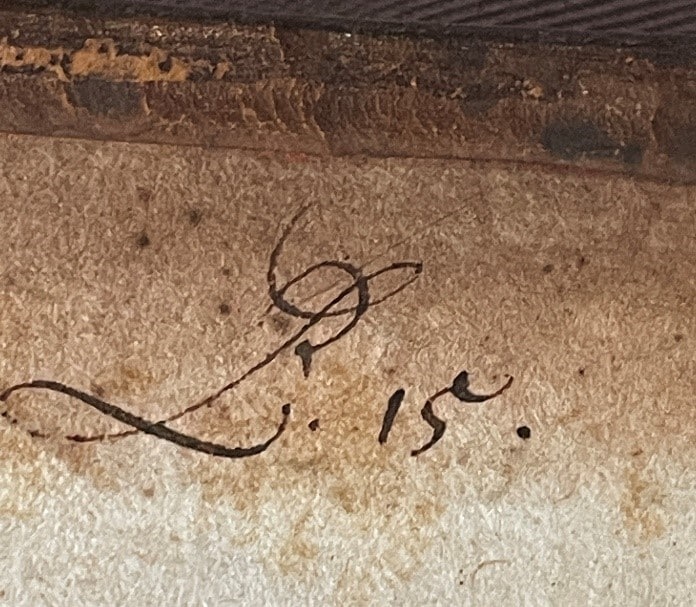

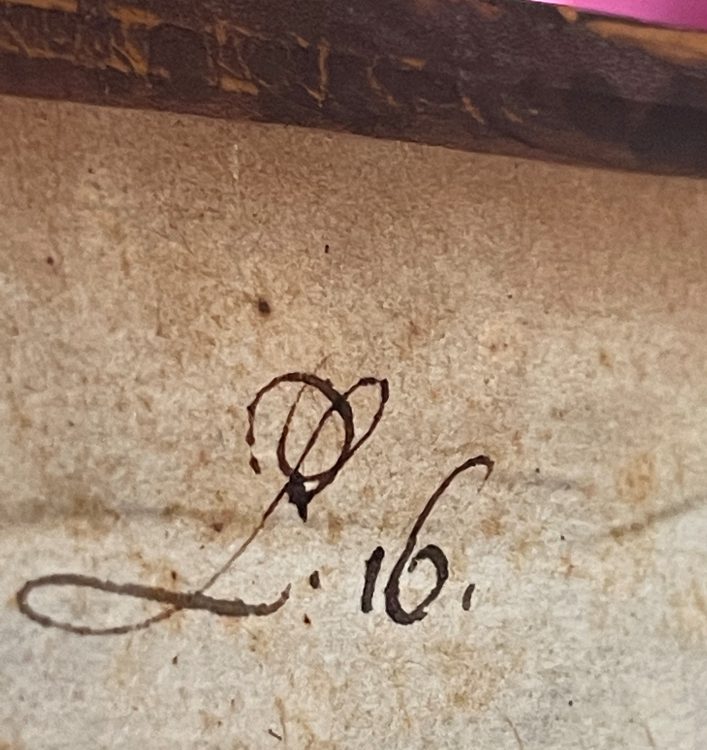

In Hearne’s specific example, the price of the Geographia ordine litterarum disposita, the two volume geographical dictionary by Michel-Antoine Baudrand, the books themselves may offer some ontrary evidence. Hearne claims that the price of 30 shillings is an overestimate of its common value of 15 shillings. However, the two volumes of our copy each have marks on the endpapers which might be a book seller’s prices, volume one has a symbol followed by’15’ and in volume two the same symbol followed by ’16.’ Has Hearne, in his zeal to accuse Mill, conflated the price of a single volume of the work with that of the complete text? None the less there is still a short fall of five shillings with the £1 16s claimed in the Ledger Book.

Hearne’s other example: the five guineas of ‘Littleton Powis’

Apart from the books paid for by Cherry, Hearne cites another case of underhanded book buying by Mill:

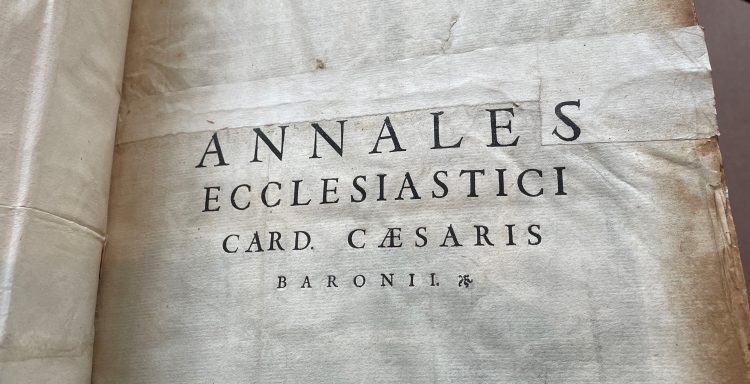

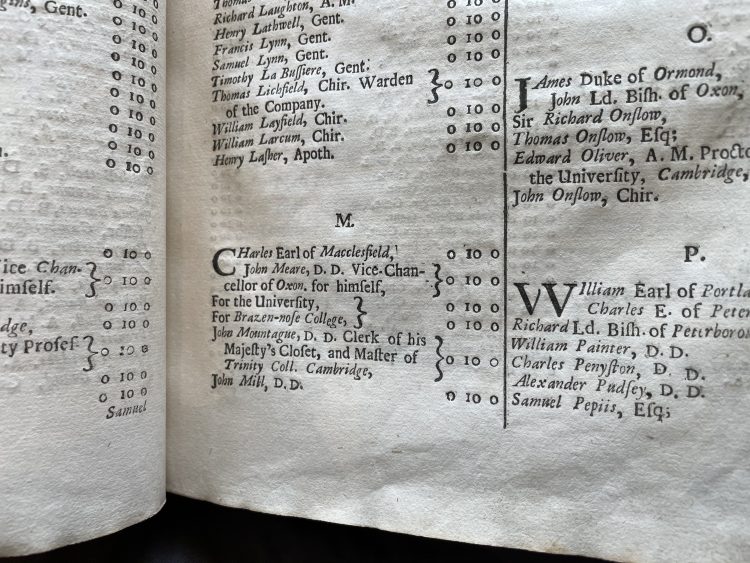

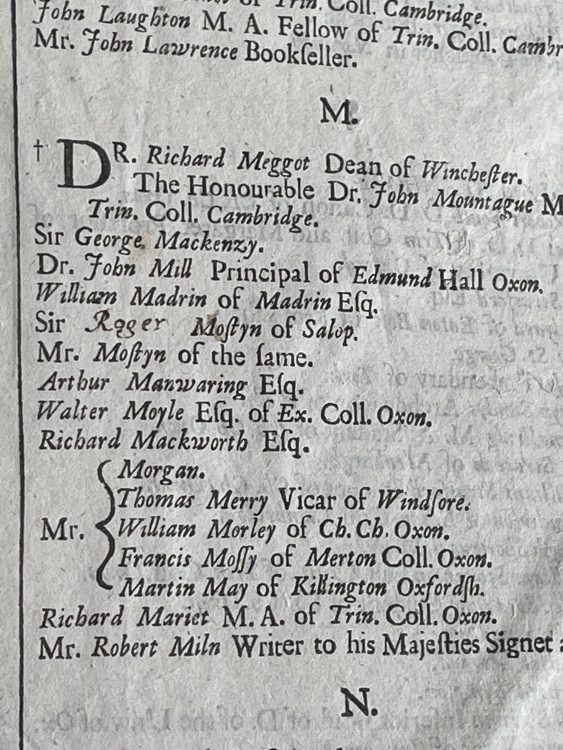

“Likewise when Sr. Littleton (Quaere?) Powis a few years since gave 5 Guineas to buy Books, Dr. Mill buys Baronius’s Annals in 12 Volumes which he claps into his own Study, and in room of it puts another Edition in six Volumes not a quarter of ye Value, and puts down the Price 5 Guineas. Also he put down Brown of the Muscles 20 shills. which cost him but 10, as appears from his Name among ye Subscribers printed.”

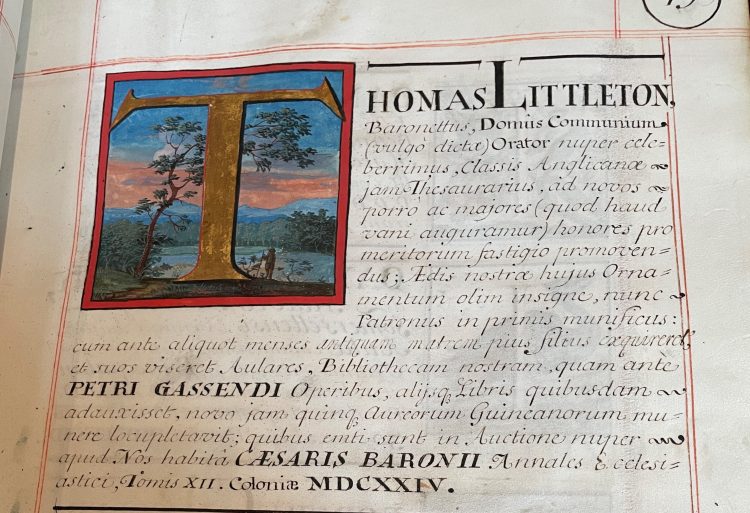

Hearne has mistaken the identity of the donor (of whom he was obviously uncertain, hence ‘Quaere?’ in his note). The Aularian in question was not Littleton Powys (mat. 1683) but rather Sir Thomas Littleton (mat.1686), whose donation is recorded in the Benefactors Book including the detail that it was used to purchase Baronius’ Annals. The donation appears to have been made in 1701 judging from the surrounding entries, during the period that Littleton was Speaker of the House of Commons (1698-1702).

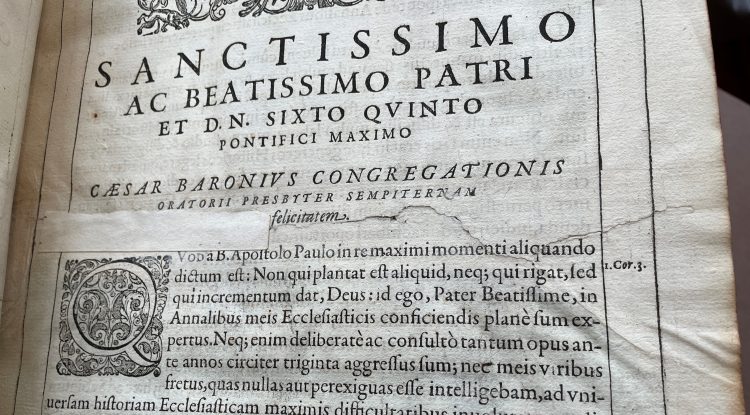

The broad details of Hearne’s account appear to be true in that the Library does hold a six volume copy (or rather 12 books bound into six volumes) of Caesar Baronius’ annals of the first 12 centuries of Christian history rather than a copy in 12 individual volumes. However, it shows no signs of previous ownership by Mill and is certainly the copy the that is referred to in the Benefactor’s book (which notes the book is the edition published in Cologne in 1624). On the other hand, it is a rather battered copy with some tears rather crudely repaired with what looks to be fairly contemporary strips of paper and if it arrived in the Library in this condition, it is hard to imagine the set costing five Guineas. If Mill was taking new books directly into his study rather than moving them to the Library, this might also explain the fate of the copy of Chardin’s Travels from the list of Partridge’s books which doesn’t appear in any Library catalogue.

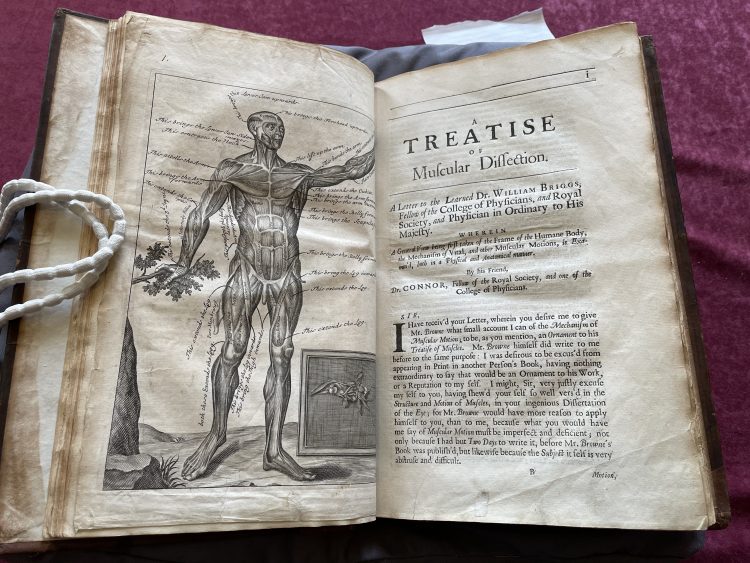

It is also true that the Library does hold the other book Hearne mentions, John Browne’s Myographia nova: or, A graphical description of all the muscles in the humane body, as they arise in dissection and that Mill was a subscriber to its publication at ten shillings although again there is nothing to mark our copy as Mill’s.

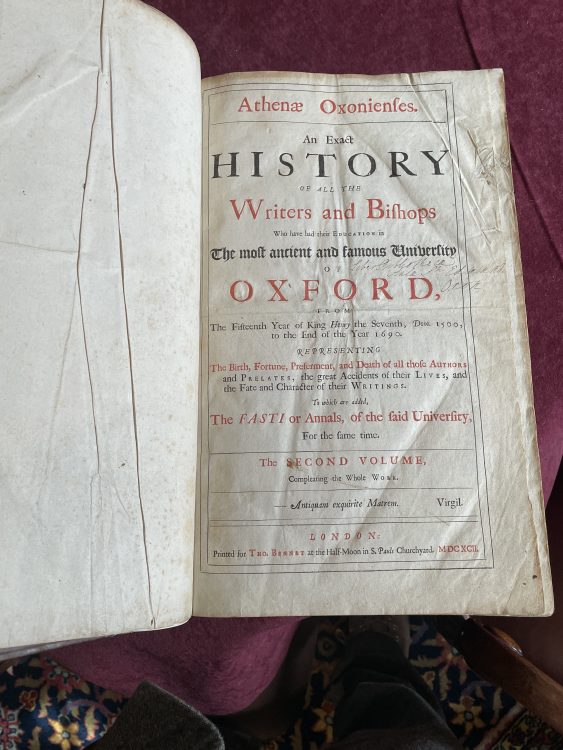

It is striking though that one of the books on the list of books bought with Partridge’s money, the second volume of Anthony Woods’s Athenae Oxonienses is also a volume to which Mill had susbcribed. Indeed in the recent cataloguing of the Old Library, the cataloguers assumed the second volume to be Mill’s on the basis of his subscription.

Aftermath: “’tis the reason he has not been a farther Benefactor”

If Mill was engaged in malpractice in regard to donations to the Library, it was a rather risky proposition. Cherry, Partridge and Littleton had all made previous donations to the Hall and might be expected to again if treated well. However according to Hearne, Cherry did indeed ask for an account or how the money was spent and “when M’. Cherry understood he much resented; & ’tis the reason he has not been a farther Benefactor.”

Mill may have intended to put matters right in the end and restore the books that were rightly the Hall’s from his study and use any unspent money on books. Unfortunately, however he died suddenly and unexpectedly on the 25 June 1707, only two weeks after the publication of the edition of the New Testament he had been working on for nearly 30 years. He died intestate and his father inherited his possessions which he moved swiftly to sell. Mill’s library was sold for £200 including, Hearne bitterly noted, “…those very Books which Dr. Mill had bought wth Benefactors’ Money & put into his own Study.”

Hearne mounted a last ditch attempt to preserve the books. He sent the new Principal a note suggesting they should be removed and made secure “’till the Hall was satisfy’ d.” but he was ignored. To add insult to injury, the purchaser of Mill’s books was the nephew of Stephen Penton, the Hall’s former Principal and founder of the Library.

Cherry did indeed never make any more donations to the Hall. His circumstances also considerably declined after the death of his father from whom he inherited debts of £30,000. When he died in 1729 his rich collection of printed books was dispersed and his manuscripts were given by his wife to the Bodleian. They include a beautiful hand written manuscript made by Elizabeth I as a New Year’s gift for her Stepmother, Katherine Parr. The volume is bound with a needle work cover with Parr’s initials picked out in gold and silver thread that is almost certainly also the work of Elizabeth. It’s unlikely that this amazing artefact, or even any of Cherry’s books, might have come to the Hall even if he felt that his gifts had been valued and well used, but even the slightest prospect is tantalising. The whole story, I think, reminds us (well me especially as Librarian) of the importance of celebrating and acknowledging the extraordinary generosity that Aularians have displayed for centuries towards the Hall and to the Library in particular.

Read more on the blog

Category: Library, Arts & Archives

Author

James

Howarth

James has been St Edmund Hall’s Librarian since May 2018. He is responsible for maintaining and developing the library’s collections – including the historic and special collections that are housed in the seventeenth-century Old Library and is keen to promote their use in research, study and outreach.