By-Elections, 1821 Style

23 Nov 2021|Rob Petre

- Library, Arts & Archives

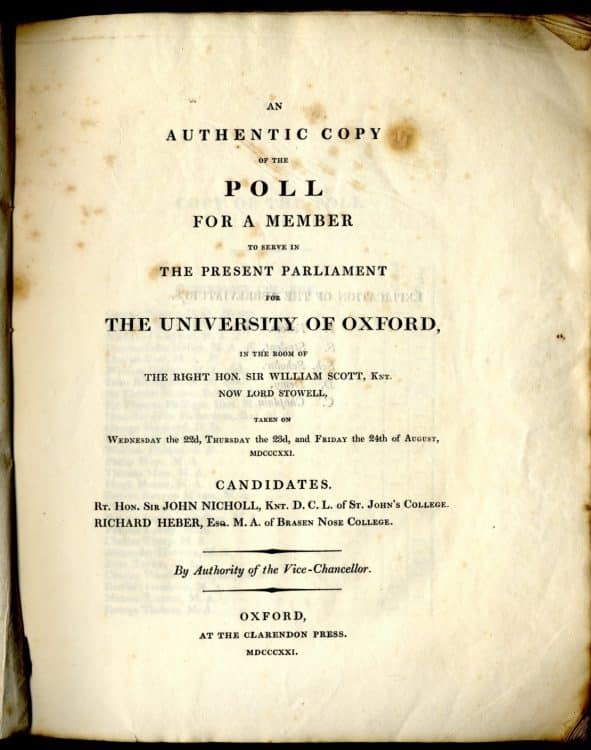

It can be a great advantage working as an archivist in two colleges, in that sometimes an item of interest for one shows up at the other. At my other place of work, Oriel, I recently took possession of a copy of the poll book for the 1821 by-election for the University of Oxford seat. (From 1603 until 1950, the University of Oxford had 2 Members of Parliament, elected by the graduates of the University. At the time of the 1821 by-election it is estimated that the total electorate would have been about 500 men.) As it shows how each Oxford society voted, it gives us a glimpse into the world of University politics just before the era of reforming parliaments.

Sir William Scott, Admiralty judge and MP for the University since 1801, was elevated to the peerage at the coronation of George IV, and so a contested election arose to replace him.

The candidates

Sir John Nicholl was a judge in the Prerogative Court of Canterbury (later like Scott becoming an Admiralty judge) and at the time of the by-election was MP for Great Bedwyn in Wiltshire, a county borough that was abolished in the Great Reform of 1832. (The village has about 1500 people living there now, so its electorate in 1821 was almost certainly less than that of the University.)

Richard Heber was noted as a book-collector (spending over £100,000 in the course of his lifetime, about £9 million in today’s money) and acted as a friend of authors, helping out Robert Southey, Sir Walter Scott, and William Wordsworth among others. He originally stood as a candidate for the University seat in 1806, but was unsuccessful.

The election

The contest was seen by contemporaries as bitter. Some on Nicholl’s side claimed that Heber was in favour of further emancipation of Roman Catholics, and Heber’s election committee had to defend their candidate against the rumours; opening up the franchise and promotion of anything other than Anglican Toryism was anathema to Oxford in the 1820s, and accusing Heber of this was ‘electioneering warfare’. Heber’s committee thanked his opponent for not sanctioning the attacks, and in the end Heber won quite handsomely.

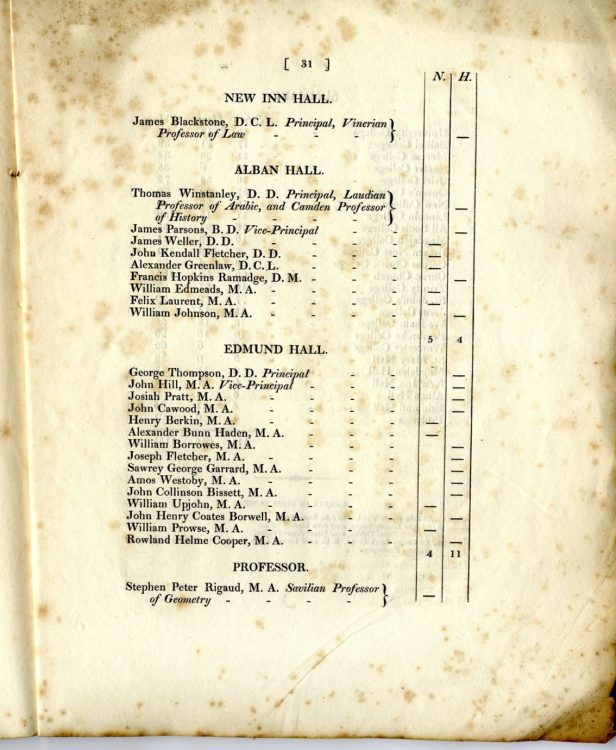

How the Hall voted

Only 15 Hall men voted, perhaps not surprising when voting was in person in Convocation. There was no secret ballot in 1821; the way men voted was noted and published; we can see that, like the University as a whole, the Hall voted for Heber.

The oddest thing

In this day and age we think nothing of ‘electioneering warfare’ during a by-election, and we almost expect smears and fake news. But both candidates in this election were from the same party, both being Tories. In fact, the Tories stood unopposed in the University elections from 1774 until 1835; in 1835 both Tory candidates stood (unopposed) as Conservatives. But the emancipation story shows just how deeply-held was Oxford anti-Catholicism; when Sir Robert Peel changed his mind and backed emancipation in 1829 he felt honour bound to resign and run again in a by-election – he lost.

Category: Library, Arts & Archives

Author

Rob

Petre

Rob is the College Archivist. His role is to preserve the documentary heritage of St Edmund Hall and to try and answer questions on any aspect of the Hall’s history with reference to our archive collection.