King Arthur & St Edmund: An Exhibition Summary

5 Nov 2019|James Howarth

- Library, Arts & Archives

Why King Arthur and St Edmund?

Partly for the challenge. One of the fun things about putting together a display of books in the Old Library is thinking of ways that different books, and their illustrations, bindings, annotations and previous owners illustrate a theme and tell a story about the Library and about the college.

But the, rather spurious, spur for this blog and exhibition came when I noticed that our copy of Edmund Spenser’s Faerie Queene had been purchased 300 years ago this October. This seemed as good a reason as any to see what other connections I could draw between St Edmund Hall and the Arthurian Legend.

Also I just like King Arthur.

So last week we opened up the Old Library to visitors and threw a book-buying anniversary exhibition and this is what there was to see:

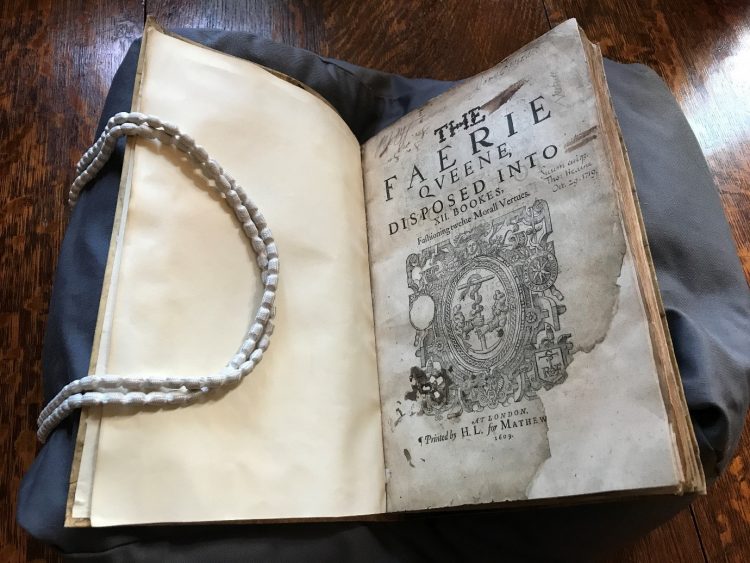

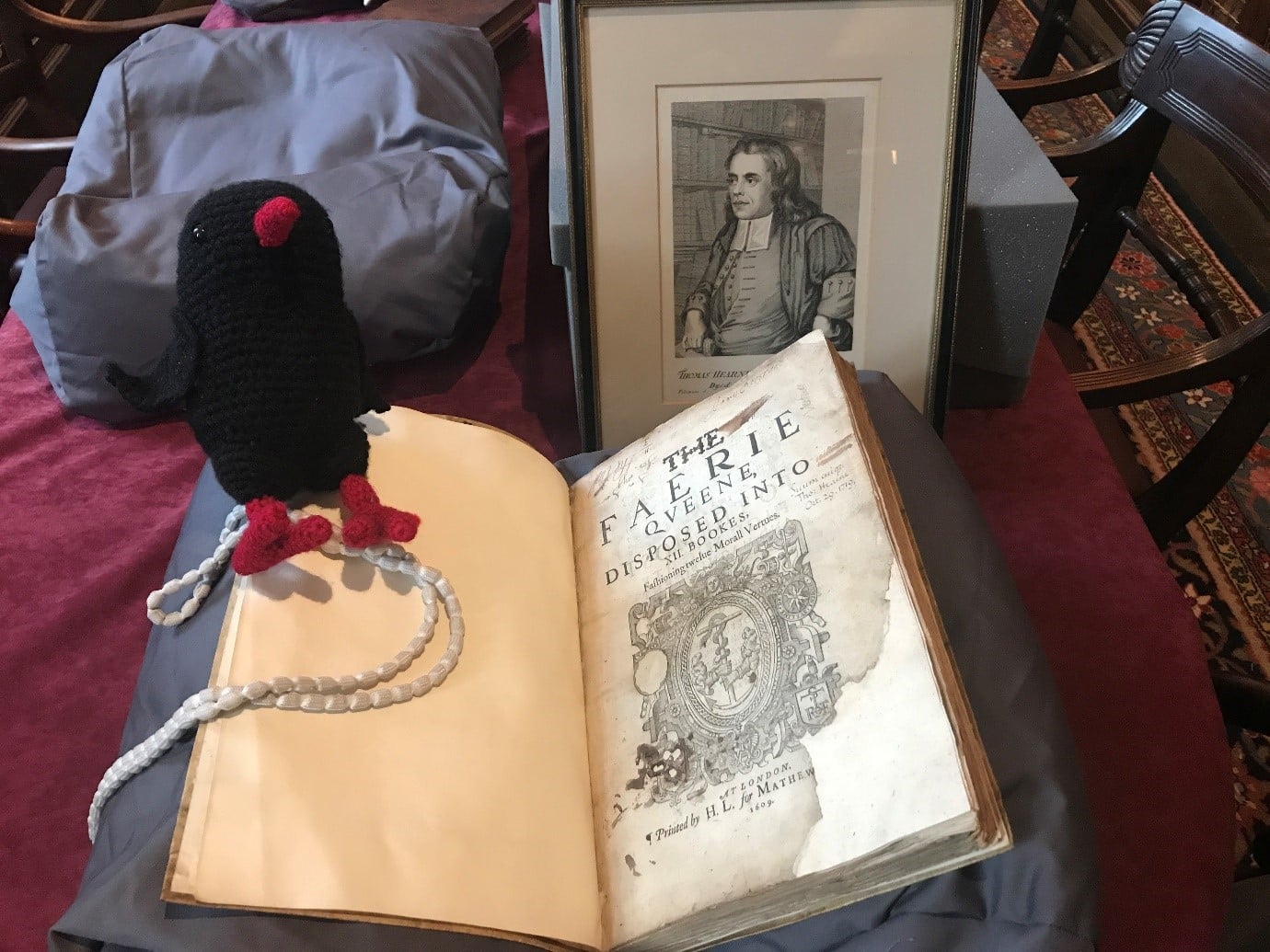

1. King Arthur and St Edmund: Thomas Hearne’s copy of the Faerie Queene

This is the first folio copy of Edmund Spenser’s allegorical poem about the young King Arthur. It includes material which had not appeared in the two previous quarto editions. The poem is one of the most significant works of the Elizabethan renaissance.

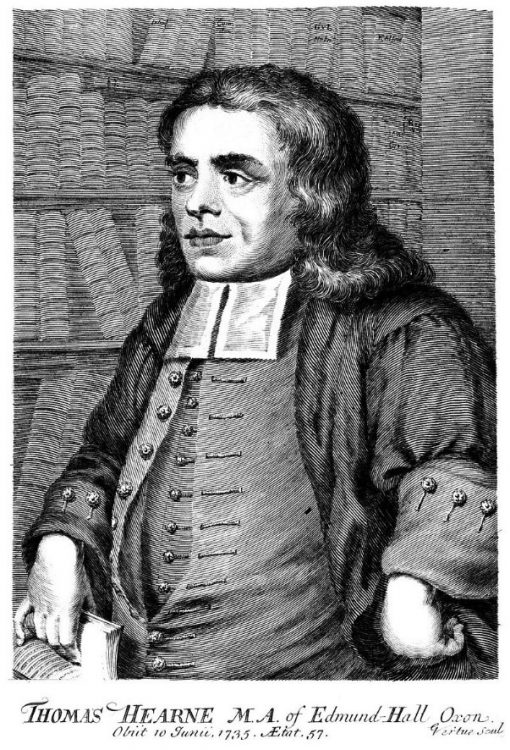

Our copy belonged to the antiquary & bibliophile Thomas Hearne (matriculated 1695), one of the most distinguished scholars to graduate from St Edmund Hall. He purchased it 300 years ago exactly, on 29 October 1719.

Hearne’s diary survives in the Bodleian. The entry for that day doesn’t alas mention book buying, but finds him contemplating reading the Ashmolean copy of the works of Athanasius Kirchner, ‘a great scholar & antiquary but in many respects whimsical.’ He also received an enthusiastic letter from a subscriber to one of his own books.

Hearne was still living in the Hall when he bought the book, indeed was still living here when he died in 1735. A room traditionally supposed to be his still exists and is used today for teaching. He produced the first catalogue of the books in the Old Library in 1699 and is buried in the churchyard of St Peter-in-the-East which is now the College’s Library.

Hearne’s books, including this one, were dispersed in a sale in 1736. It came back to Teddy Hall nearly 200 years later when it was donated to the Library by AB Emden, Principal of the Hall from 1929-1951.

2. A historical Arthur?

The question of Arthur’s existence was hotly debated in the Early Modern period. The Italian humanist Polydore Vergil, Henry VII’s court historian, had poured scorn on the reality of the legend at the beginning of the 16th century. Afterwards patriotic British antiquarians such as John Leland and William Camden sought to establish a historical basis for Arthur.

2.1 Thomas Hearne as an antiquarian publisher and editor

Thomas Hearne was convinced non-juror and Jacobite, that is he rejected the deposition of James II in 1688 and in particular the accession of Hanoverian dynasty in 1714. His refusal to swear an oath of allegiance to George I stymied his career at Oxford. Matters came to a head in 1716 when he lost his position as Second Librarian at the Bodleian when Bodley’s Librarian literally changed the locks and stopped him coming into work.

Thereafter, Hearne made a living by publishing editions of medieval works and other antiquarian material to subscribers. Inevitably this included material about King Arthur.

Hearne published works from both sides of the debate about the existence of Arthur, from John Leland’s passionate defence, the Assertio inclytissimi Arturii regis Britanniae, to the chronicle of William of Newburgh, one the first medieval writers to doubt it.

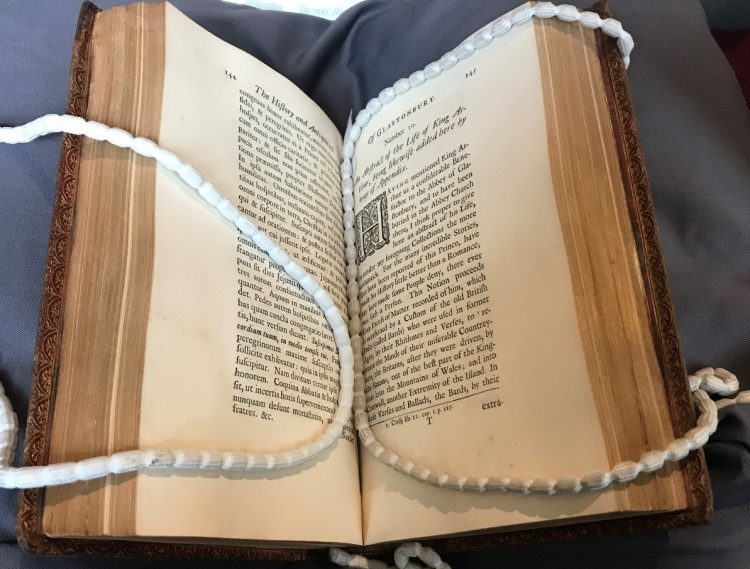

Displayed here is a contemporary work published by Hearne. The history and antiquities of Glastonbury was written anonymously by a Catholic author named Charles Eyston, who in an appendix sums up the evidence that Arthur was real.

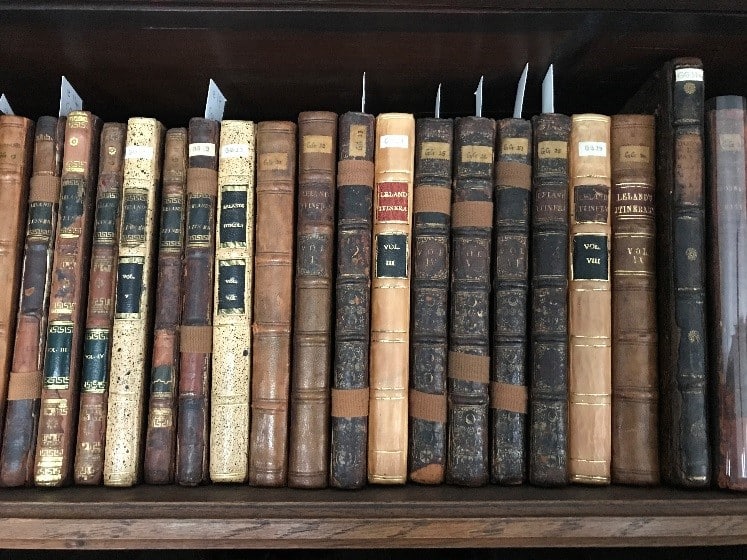

We hold an extensive collection of Hearne’s editions, taking up four shelves of space in the Old Library.

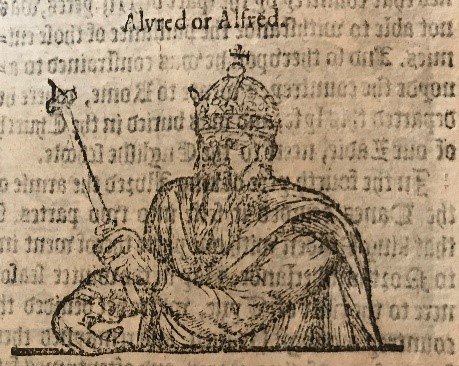

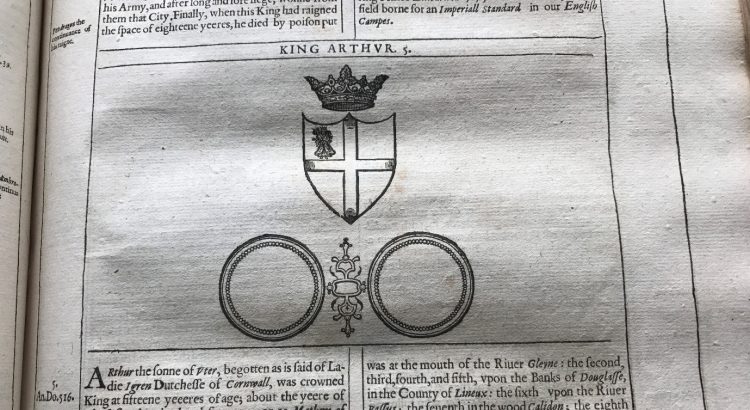

2.2 Picturing history with Raphael Hollinshed

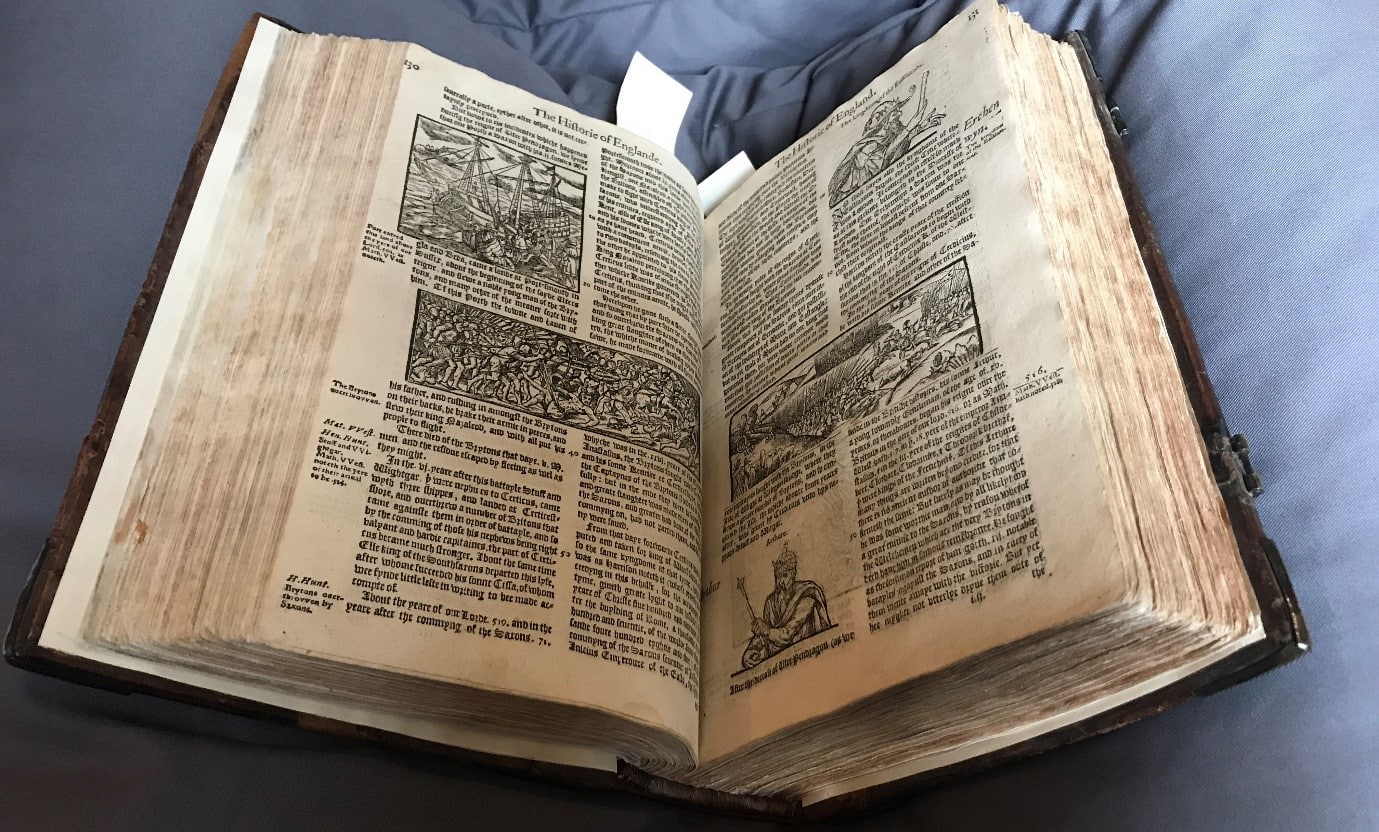

Holinshed’s Chronicles are an ambitious attempt to cover the whole history of Britain. The first volume covers English history to 1066 as well as the history of Scotland and Ireland. It is an important source for Shakespeare’s Macbeth and King Lear.

His account of Arthur sticks close to that of earlier Medieval chroniclers and he is sceptical of the more romantic parts of the story and outlandish claims of Arthur’s European conquests: “the Britains are thought to have registred meere fables in sted of true matters, upon a vaine desire to advance more than reason would, this Arthur their noble champion.”

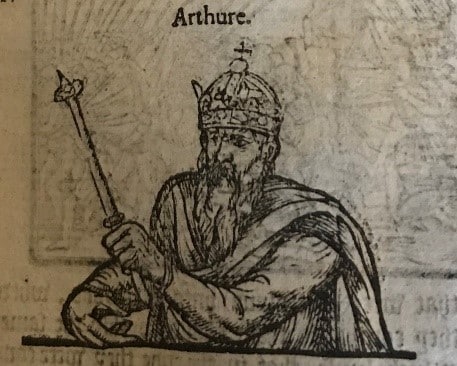

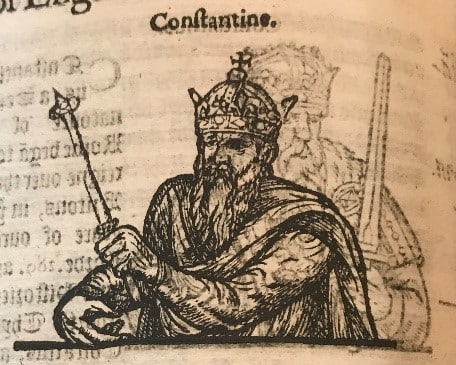

The book is lavishly illustrated with woodcuts of every king and the events of their reign. However, the same images are reused time and time again. For example, the figure here labelled ‘Arthure’ is also used for the Roman Emperor Constantine and for Alfred the Great. This creates a strange almost dream-like version of history as the same battles seem to be continually rethought and the same figures reappear constantly.

Our copy has been in the Library since 1770. By the late 20th century the book’s condition had deteriorated significantly and it could not be read. In 1984-5 it underwent a thorough repair at the hands of the Bodleian conservators and is now good for at least another 200 years!

Restoring Holinshed’s Chronicles: Before & After

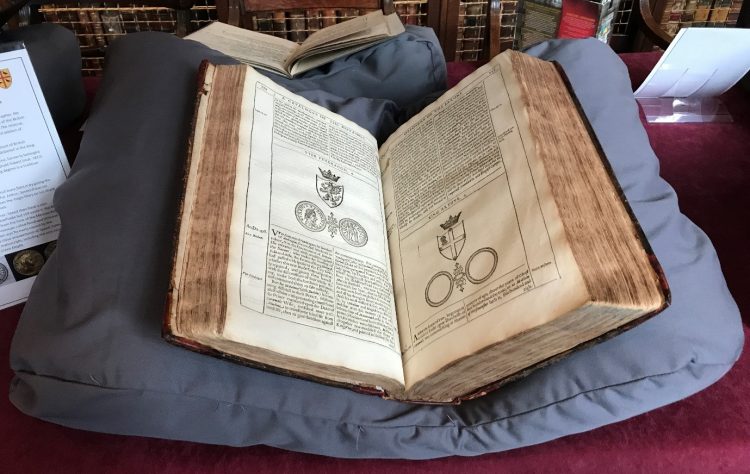

2.3 John Speed and a mis-identified coin

John Speed (1552-1629) is perhaps best remembered today as a cartographer. His Theatre of the Empire of Great Britaine is the first comprehensive atlas of the British Isles containing maps of each county and comprehensive town plans. The Historie, displayed here was conceived as a companion to this work, in the first edition of 1611-12 they even have continuous pagination.

In his account of British History, Speed is concerned to preserve the historicity of Arthur. Like Hollinshed, he blames the excesses of romance for creating doubts about King Arthur’s existance.

We hold two copies of Speed’s work. One, like our Faerie Queene, formerly belonged to Thomas Hearne. The other was given to the Library by Reginald Rabett (mat. 1813) on his graduation in 1816, the giving of a book after receiving a degree is a tradition that goes back to the 1660s at St Edmund Hall.

A coin of Uther Pendragon?

One way in which Speed’s work tries to assert its historical bona fides is by giving the coat of arms and an engraving of a coin for each king. For Arthur, Speed draws on tradition first found in a 9th century chronicle and shows the Virgin Mary on his shield but unsurprisingly he can find no coin to ascribe to him.

However, for Arthur’s equally legendary father Uther, Speed does have a coin. Amazingly, the actual coin pictured is not only identifiable but still exists in the British Museum. What is depicted in the book is a coin from the time of the Mercian King Offa (reigned 757-796) produced by a London moneyer called Pendraed (misread by Speed as ‘Pendragon’). The British Museum coin was formerly owned by the Antiquarian Sir Robert Cotton (1571-1631), a close acquaintance of Speed. Cotton had an extensive collection of artifacts and manuscripts, including the only surviving copies of Beowulf and Sir Gawain and the Green Knight.

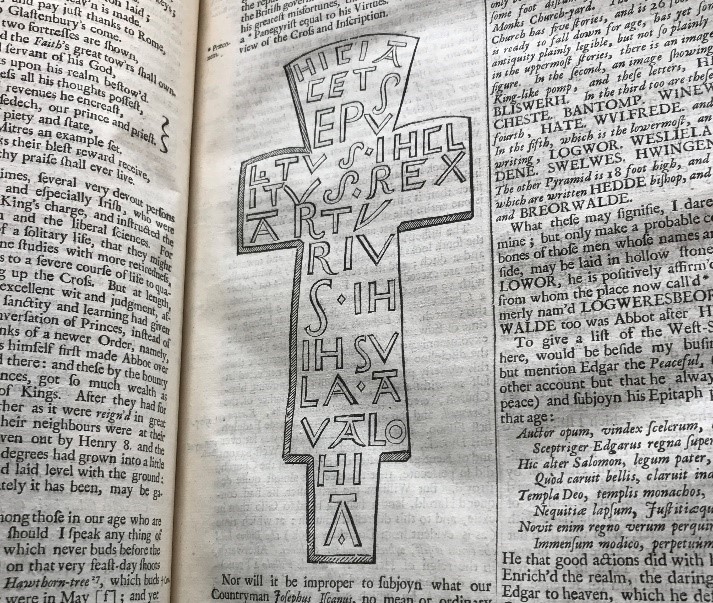

2.4 William Camden and King Arthur’s Grave

In 1192 the monks of Glastonbury Abbey announced an amazing discovery: they had unearthed the grave of King Arthur. This has been met with scepticism not just from modern historians but also at the time. The Abbey had form in this area and, having burnt down 10 years previously, was in need of funds and a new attraction. A large lead cross was found with the grave bearing an inscription identifying Arthur.

The bones were installed in a fine new tomb in the centre of the abbey which was destroyed during the dissolution of the monasteries. The mysterious cross has also been lost, but many descriptions survive.

However, the only illustration of it appeared first in William Camden’s Britannia, a wide ranging survey of historical and topographical material covering the whole island of Britain.

Camden, an historian and herald, aimed with this work ‘to restore Britain to Antiquity, and Antiquity to Britain.’

“Hic iacet sepultus inclitus Rex Arturius in insula Avalonia.”

“Here lies buried the renowned King Arthur in the Isle of Avalon.”

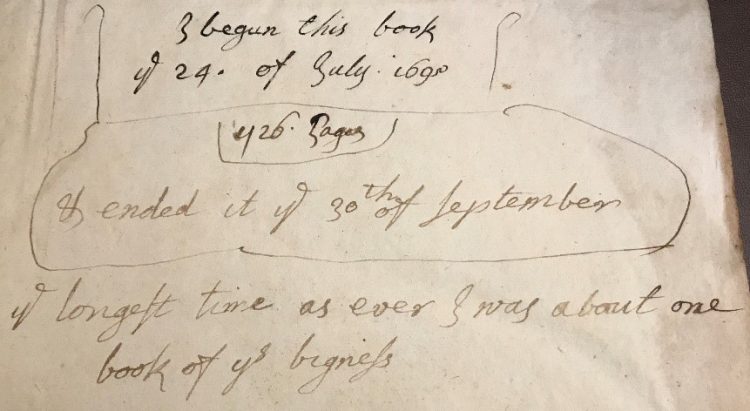

Camden’s work was composed in Latin, but our copy of Britannia is a later English translation first published in 1695.

Despite it not being in Latin, an early reader of our copy (perhaps the books’ original owner) did not find it an easy read.

A note at the front records in a neat, confident hand that the reader began it on the 24th of July 1698, with a note of the length (426 pages). Sixty-eight days later, a more scrawled entry marks the completion of the read on the 30th of September. ‘Ye longest time as ever I was about one book of this bigness’ is the reader’s rather despondent final comment.

3. The Return of King Arthur 1765-1894

After Spenser, there were no major works of literature or poetry about King Arthur for more than a century (or no successful ones anyway as we will see later). Antiquarian and historical interest in the story focussed on concrete details not magical quests. However, beginning in the later eighteenth century there was a huge revival of interest in medieval stories, both academic in the editing and publishing of texts, but also and more broadly in the subjects of those texts, in chivalry and sorcery and, inevitably, in King Arthur and his knights.

3.1 Bishop Percy’s Reliques of English Poetry

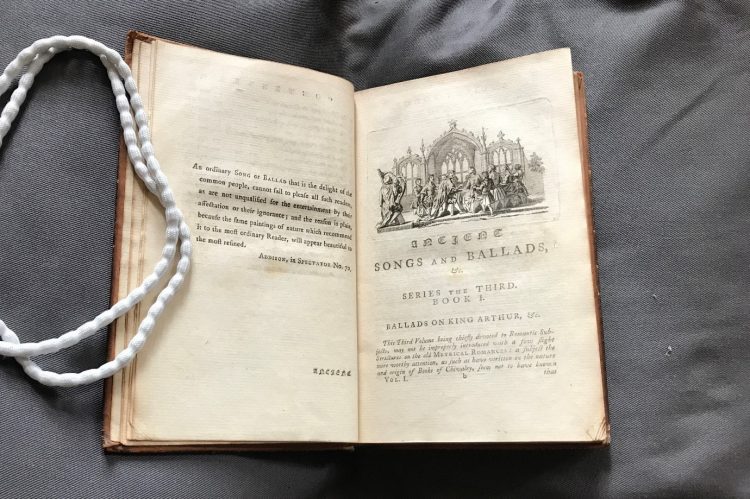

The three volumes of traditional ballads and broadsides published by Thomas Percy were immensely influential on European romanticism, paving the way for poets such as Burns, Wordsworth and Coleridge. ‘In this country poetry has been absolutely redeemed by it’ wrote Wordsworth in an essay in the 1815 edition of Lyrical Ballads. Percy collected his material from a wide variety of sources including a manuscript he claimed to have rescued from a maid who was using it to kindle a fire!

The third volume opens with an essay on metrical romance and features five ballads on Arthurian subjects. King Arthur is pictured at the Round Table listening to a bard.

3.2 Walter Scott and the Medieval Revival

Walter Scott’s most important contribution to the revival of interest in King Arthur in the 19th century is indirect and comes from the vogue for an idealised version of Britain in the Middle Ages his works inspired, but he also produced some work directly on the legend.

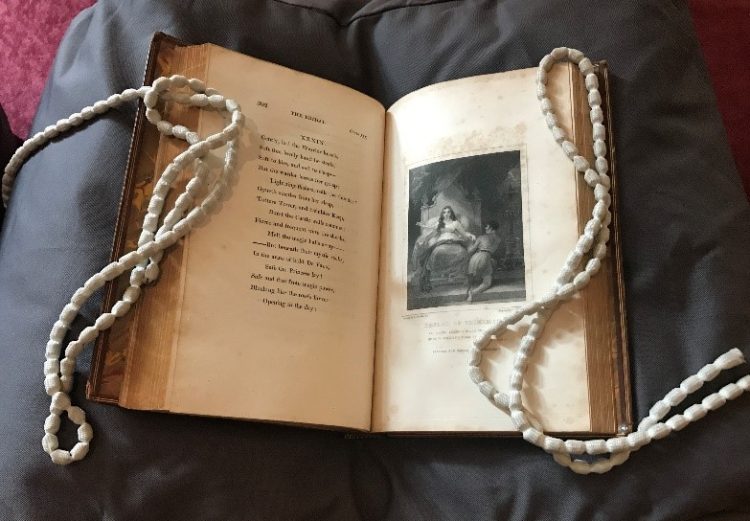

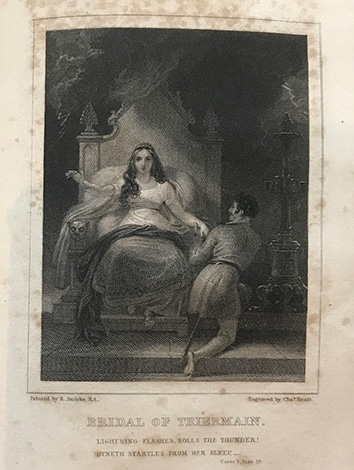

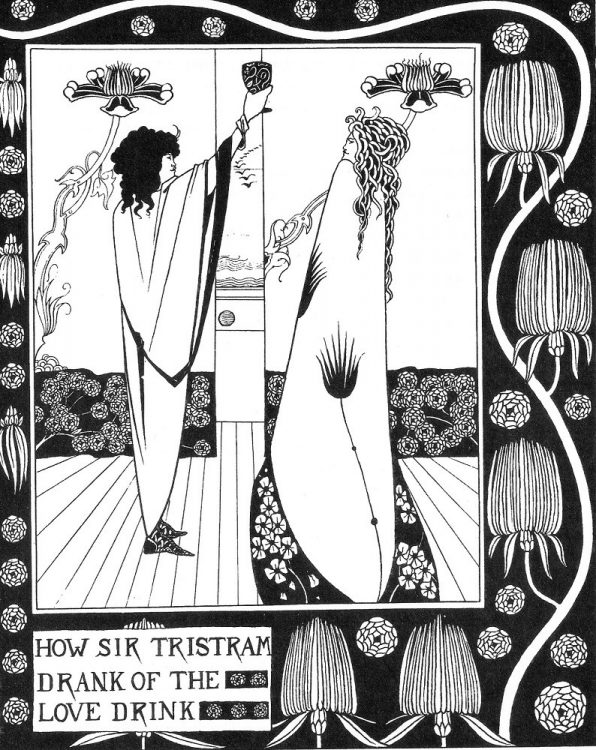

‘The Bridal of Triermain,’ Scott’s only original Arthurian work combines the stories of King Arthur and Sleeping Beauty. In the poem, a young Scottish knight strives to wake Arthur’s daughter from a 500-year enchanted sleep.

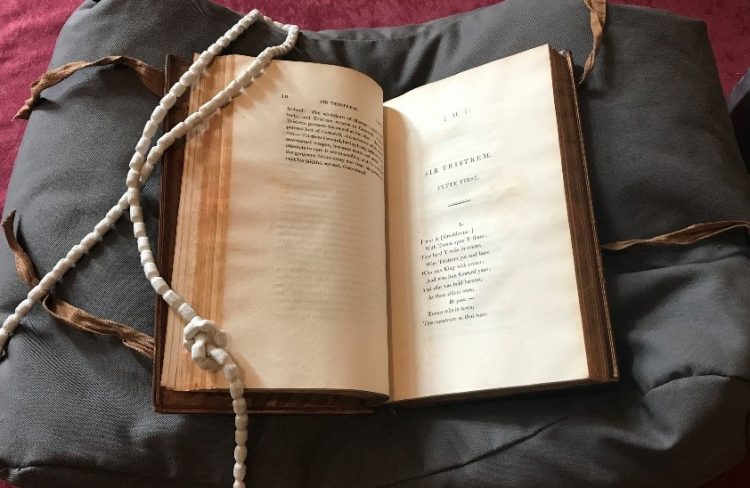

Scott also produced an edition of the Middle Scots poem Sir Tristrem. Although slipshod by modern academic standards, the work, which includes a comparison of the poem with other medieval versions of the Tristan legend, looks forward to the more systematic study of Medieval Literature which gathered pace across the 19th century.

Both of these volumes come from the first complete edition of Scott’s poetry.

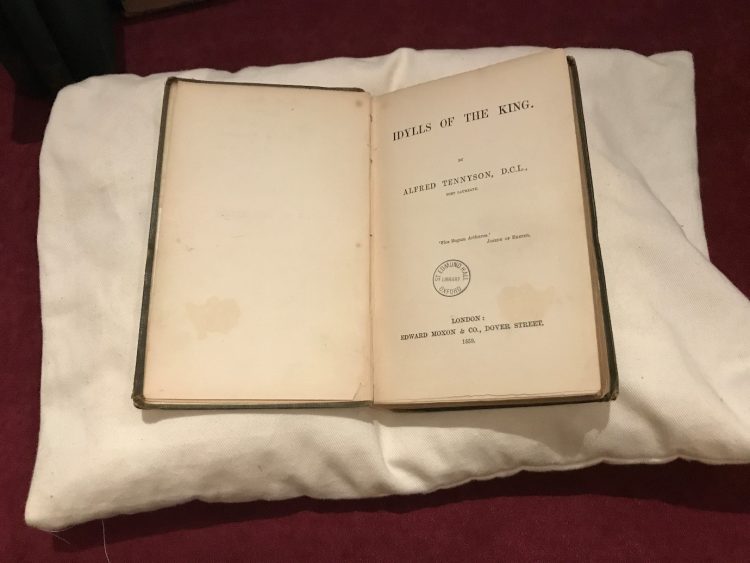

3.3 ‘The old order changeth, yielding place to new’: Tennyson’s very Victorian Arthur

Tennyson’s cycle of poems about King Arthur are probably the most influential Arthurian work of the 19th century.

Tennyson recreates the Round Table in the image of high Victorian morality, stripping away moral ambiguity and perceived vulgarity. As such, he owes almost as much to Spenser’s earlier allegorical work in the Faerie Queene as to Thomas Malory’s Morte D’Arthur which is the more direct source of his narrative.

The first four poems appeared in 1859 with another eight following over the next twenty-six years. We hold first editions of all of them, part of a large bequest of English literature given to the Hall in 1986 by Harold Brooks, a professor at the University of London. Brooks was an expert on the 17th century poet John Oldham, who was an alumnus of St Edmund Hall.

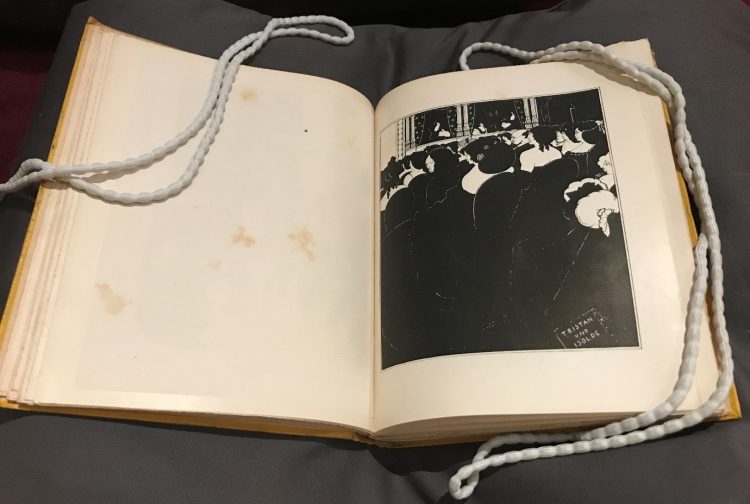

3.4 Arthur in the 1890s

This is one of four drawings by the decadent artist Aubrey Beardsley in the third issue of the Yellow Book. Like Oscar Wilde and other members of the 1890’s aesthetic movement, Beardsley was a keen enthusiast for Wagner’s music and avidly attended performances.

One of the members of the largely female audience can be seen holding the libretto for Wagner’s Tristan & Isolde and Beardsley maybe mocking the idea that female admirers of the composer were overcome by the passion of the music as the protagonists of the story were by the magic love potion. There may also be a deliberate echo of Toulouse-Lautrec’s pictures of more raucous music hall audiences.

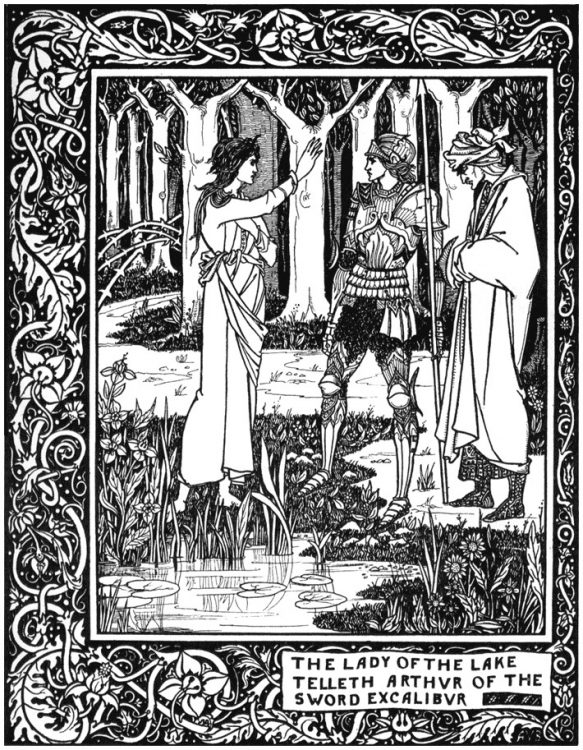

Beardsley also produced more explicitly Arthurian work. His first major professional commission was to provide illustrations for an 1893 edition of Malory’s Morte D’Arthur.

4. Aularian Arthurs

Our collection of works by alumni of St Edmund Hall, ‘Aularians’ as we call them, is one the biggest treasures of Library, representing the academic, literary and cultural achievements of generations of our students. Several Aularians have tackled the Arthurian legend, with, it’s fair to say, differing levels of success…

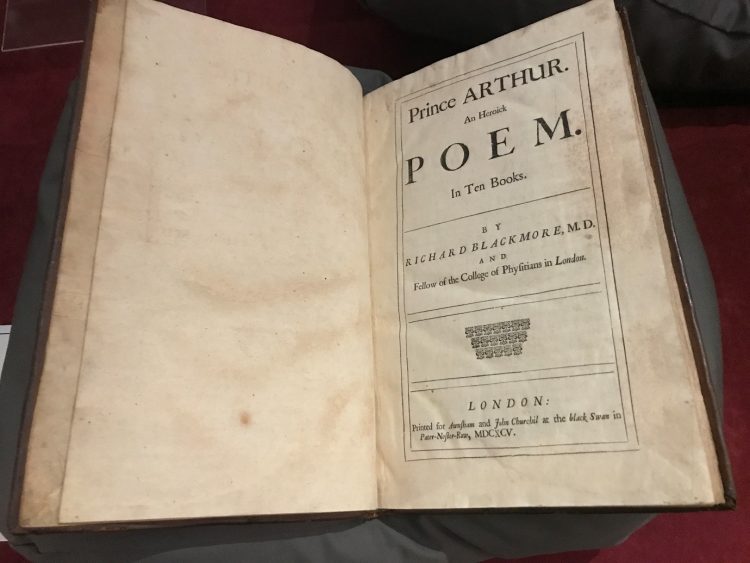

4.1 Aularian Arthurs: An epic fail

Richard Blackmore (mat. 1669) attended the Hall whilst it was experiencing a brief period of fashionability and growth. A successful and well regarded physician he also attempted a literary career. Prince Arthur, an epic in the style of Vergil, is one of the few works of Arthurian literature published in this period.

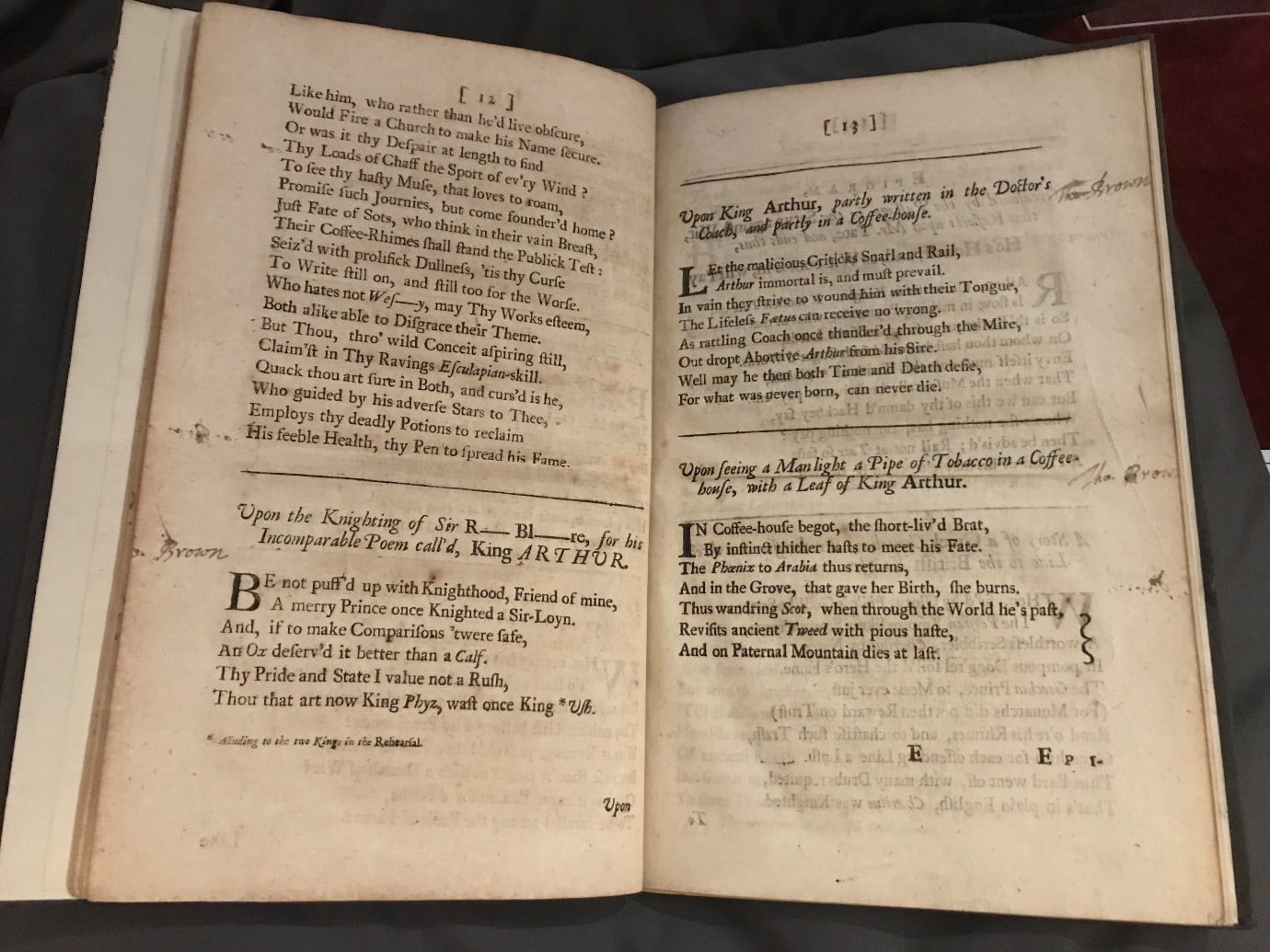

It was not well received and much lampooned. Blackmore published a sequel King Arthur (1697) attempting to address some of the criticisms, it was not republished. The Library holds a unique copy of a book of 40 poems mocking Blackmore where the anonymous authors have been meticulously noted in the margins.

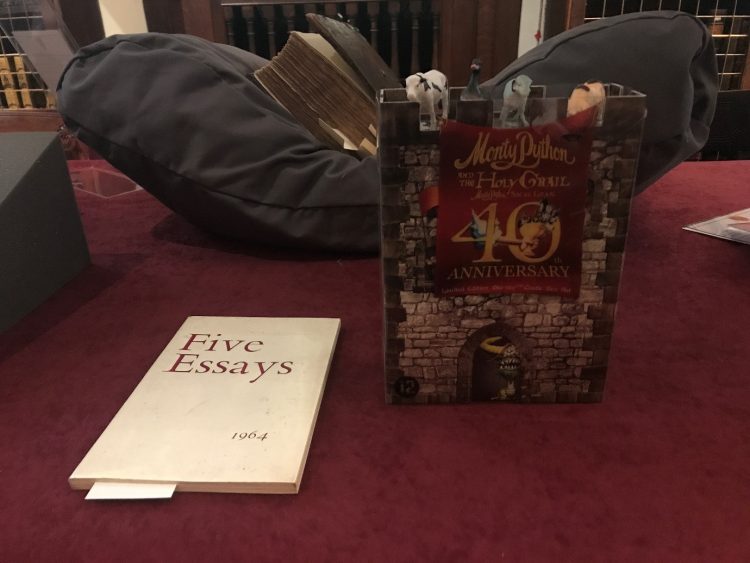

4.2 Aularian Arthurs II: Now for something completely different

Monty Python and the Holy Grail is much more intentionally comic than Richard Blackmore’s poem. Terry Jones (mat. 1961) and Terry Gilliam volunteered to direct the film although they were novice film makers and all five Pythons contributed to the script. Regularly appearing in lists of the funniest films of all time, many of its scenes are now themselves legendary. But this is not the first time Jones had satirised a beloved literary figure…

Satire, parody, even flat-out absurdity have long played a significant part in student humour in Oxford. Societies and clubs dedicated to making fun of anything or even everything have flourished throughout the University’s history and it was in this atmosphere that Jones cut his comic teeth.

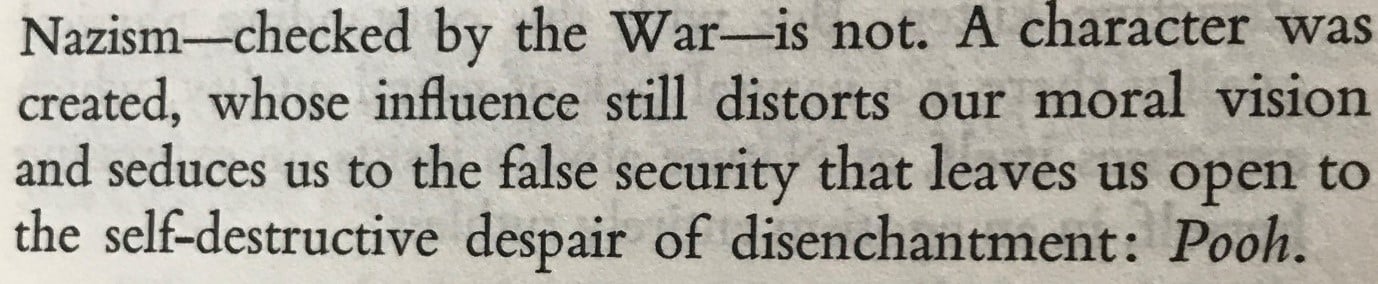

In this early piece, which adopts the form of a censorious academic essay, Terry Jones reveals ‘the most perverting writer’ to be AA Milne, the author of Winnie-the-Pooh.

The essay reaches a shocking conclusion:

It appears in a book published by the Hall’s ‘Makers Society,’ represented as an essay society meeting regularly to review each other’s work. We have to say we are not sure if this society actually existed as a, presumably humorous, club or is itself part of the satirical intention of the book’s five authors.

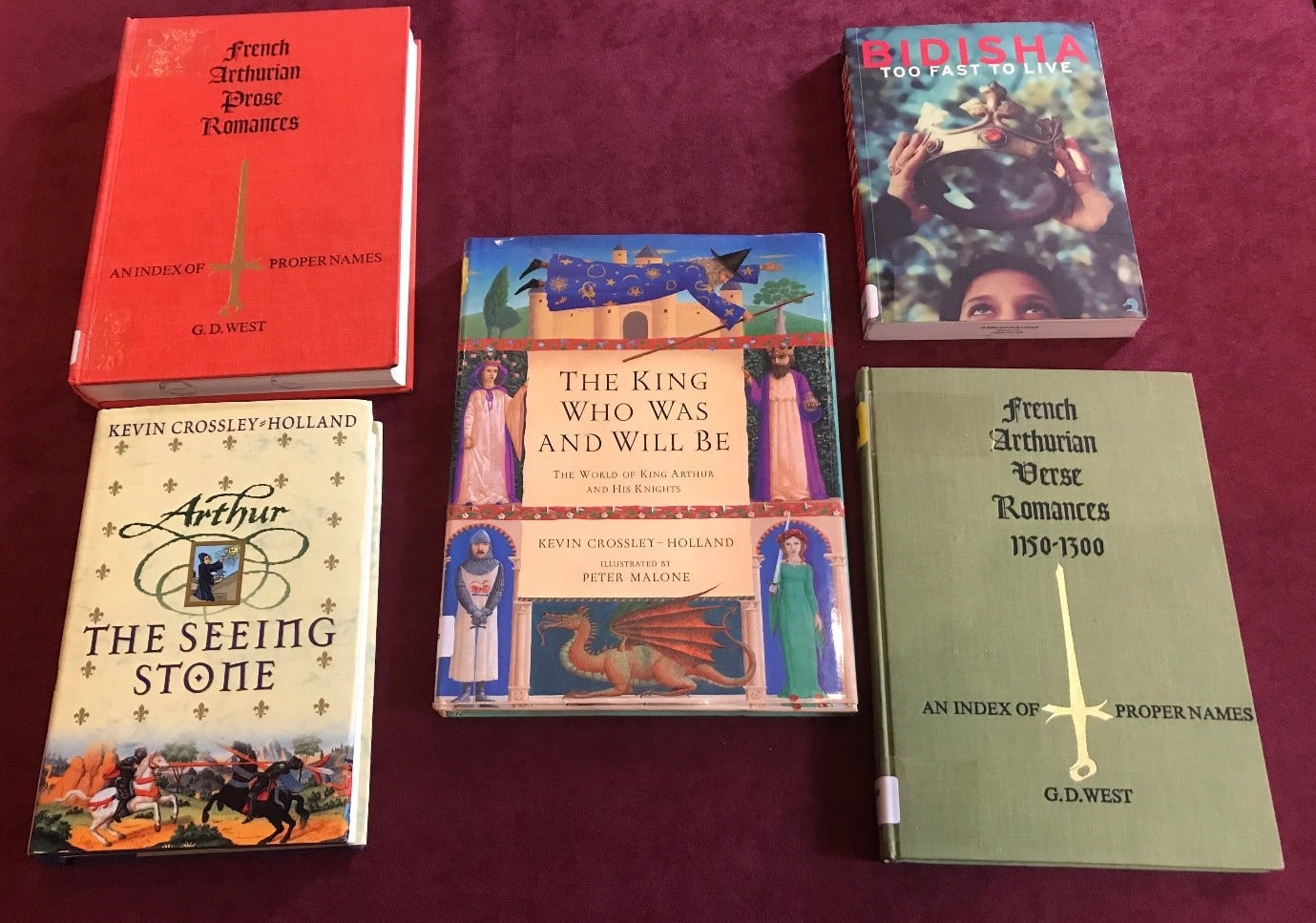

4.3 Other Aularian Arthurs

Bidisha (mat. 1996) is a British writer, film-maker and broadcaster/presenter. She specialises in international human rights, social justice, gender and the arts. Too fast to live is a reinterpretation of the Arthurian legends, set in contemporary London. It is both an extension and inversion of the Camelot story.

Kevin Crossley-Holland (mat. 1959) has written translations of Anglo Saxon verse, books of folklore and mythology and historical fiction for both children and adults. Arthur: the seeing Stone is the first in a trilogy of novels in which a mediaeval boy experiences magical parallels between his life and the legend of King Arthur.

George Derek West (mat. 1940) was Professor of French at Mcmaster University in Ontario, Canada. He was a distinguished scholar of Arthurian romance. The Librarian is, in fact, a bit of a fan, and used West’s works extensively when writing in his master thesis on Middle English Arthurian poetry. SEH

5. King Arthur and St Edmund: A Chatter of Choughs

What links King Arthur and St Edmund Hall? Well, one answer, as unlikely as it might seem is the black bird on our coat of arms – the Cornish chough (Pyrrhocorax pyrrhocorax).

There is a legendary claim that, after his death, King Arthur was not buried and Glastonbury and Avalon but instead was reincarnated as a raven or a chough while he waits to return. This story appears in Cervantes Don Quixote of all places but is also recorded by folklorists in Cornwall and the West country as late as the early 20th century.

The Hall’s arms derive from those of St Edmund of Abingdon, the 13th century Archbishop of Canterbury after whom we are named. Quite why they are his arms is more disputed: they first appear in a manuscript by Matthew Parker, Archbishop of Canterbury under Elizabeth I. He may have derived them from the arms of Abingdon Abbey or from those of Edmund’s predecessor Archbishop-Saint Thomas Beckett.

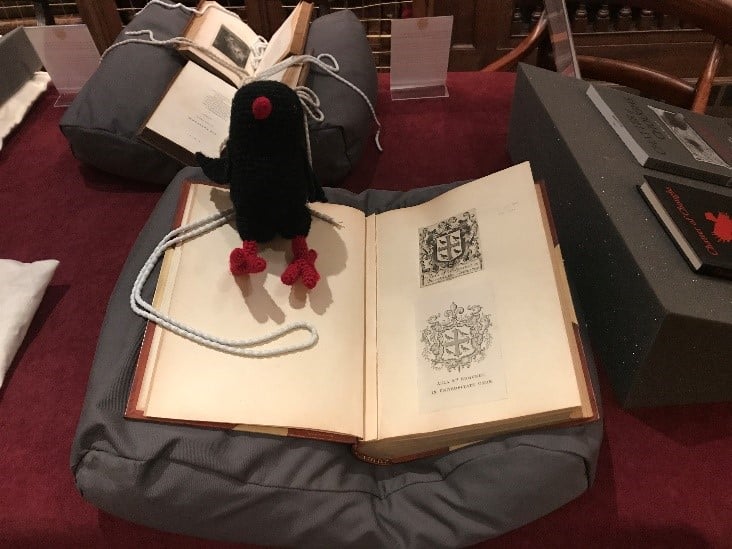

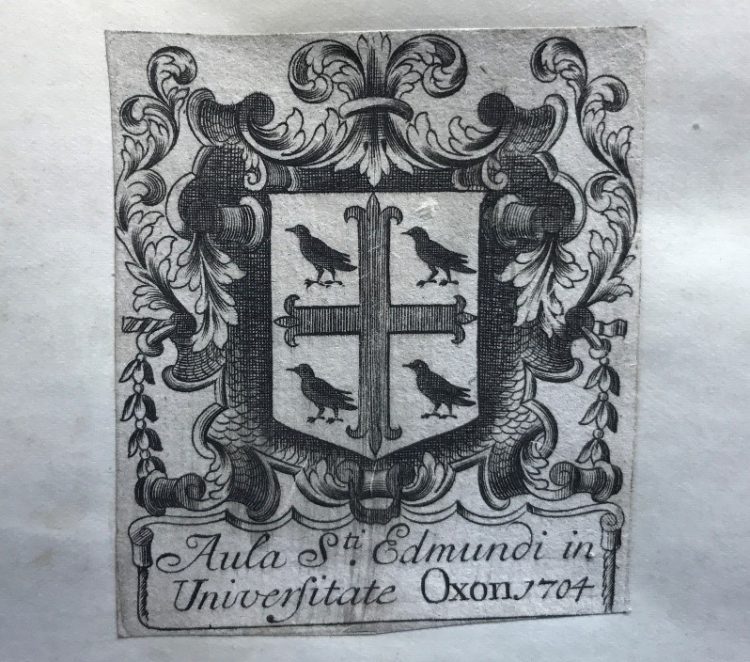

Teddy Hall has used the coat of arms since at least the middle of the seventeenth century. In 1704 the Principal’s ledger book records the payment of £1 10s for’ St Edmds Coat of Arms, & papers of his arms, printed off for ye Books in the Library.’ The original 1704 book plate can still be seen on many books in the Old Library and we still use the arms on all Library book plates today. A volume in the college archives preserves examples of all of the book plates that have been used by the Hall.

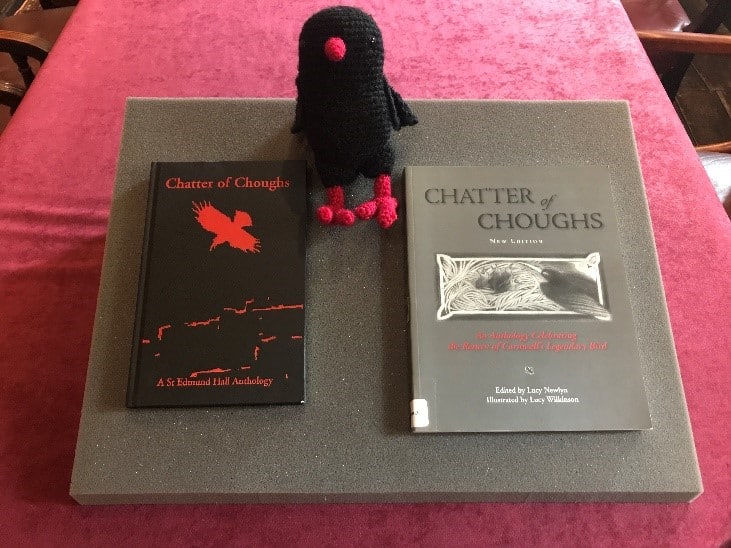

In 2001, Hall Fellow Lucy Newlyn produced an anthology of poems celebrating the chough and its connections with Cornwall, Arthur, Teddy and St Edmund. A second edition was published in 2005 to celebrate the successful reintroduction of the bird to Cornwall by the RSPB.

Finally a word of thanks to the undoubted star of the show: Nora the Chough, generously lent to us by Luke Maw, our Student Recruitment Manager, and knitted by his partner.

Category: Library, Arts & Archives

Author

James

Howarth

James has been St Edmund Hall’s Librarian since May 2018. He is responsible for maintaining and developing the library’s collections – including the historic and special collections that are housed in the seventeenth-century Old Library and is keen to promote their use in research, study and outreach.