The generous men of Kent: remembering a small group of benefactors of the Library

12 Nov 2025|James Howarth

- Library, Arts & Archives

On Sunday 16 November we will be honouring the feast day of our patron St Edmund of Abingdon and at Evensong the Principal will read the prayer commemorating him and the major benefactors of the College. However, it is also good to remember some smaller and unsung friends of the Hall.

The book collection of the Old Library is for the most part made up of small donations of volumes by Aularians and others from the time we started collecting books in 1664 to the present day. Sometime between 1682 and 1684 seven men from Kent, none of them Aularians, gave 14 books to Hall Library which was nearing completion. Before now their contribution has not been recognised.

Nomina Benefactorum: Thomas Hearne’s List of Library Donors

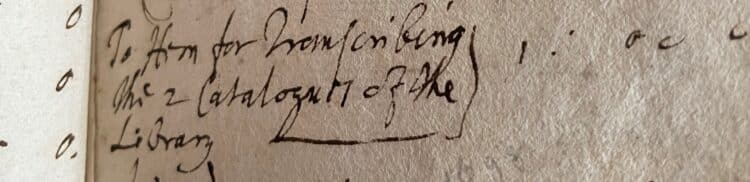

There is a note in the New Leiger [ie Ledger] Book, the Hall’s oldest surviving record, recording a payment of £1 sometime around 1698 to the Aularian Thomas Hearne (mat. 1695) “for transcribing the 2 Catalogues of the library”. Although we do not hold Hearne’s catalogues, a number of drafts survive amongst his papers held by the Bodleian. The “2 Catalogues” appear to have been a straightforward list of books and a list of donors and their gifts to the Library.

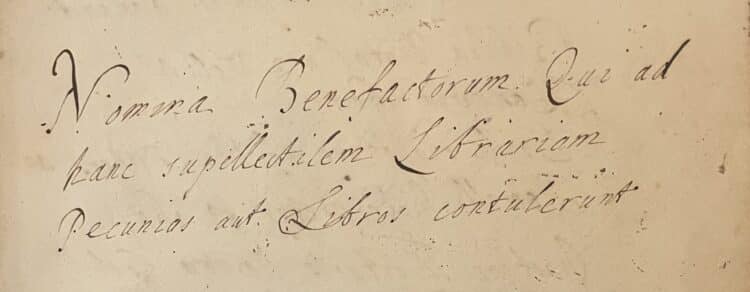

The earliest surviving drafts, again datable to around 1698, are in Rawlinson Ms D398. The list of books is a very rough document with many crossings out and some entries in an untidy scrawl, but the donor list, entitled “Nomina Benefactorum Qui ad hanc supellectilem Librariam Pecunias aut Libros contulerunt” (‘Names of benefactors who contributed money or books to this Library’s furnishings’), is in a much neater hand. It lists 32 donors and 153 books in approximately chronological order of donation. Of these, the donors of around 79 volumes would be otherwise unknown.

Many, but by no means all, of the books in the Old Library have inscriptions recording their donation, however in some cases these were not made and in others they have been lost when the front endpapers of books have been removed or replaced as part of repairs. Our magnificent Book of Benefactors only records a few Library donors: those who gave large numbers of books, or those who also gave money for the Library’s construction for example. The lists in Hearne’s manuscripts are thus of significant importance for the history of the collection.

“In Comitatu Cant.”: seven donors from Kent

On the third page of Hearne’s donor list comes a sequence of seven names, all of whom are noted as being from places in the county of Kent (“In Comitatu Cant.”). None of the donors are Aularians, although three attended other Oxford Colleges (two went to Cambridge and the remaining two did not attend university). Four were clergy and three lay men. It is with the last name that the link to St Edmund Hall becomes apparent: “Basileus Kennett, Rector de Dimchurch in Comitatu Can.”

This is Basil Kennett, who was the Rector of Dymchurch on the Kent coast from 1676-1687. Kennett sent his two sons, White (mat. 1678) and Basil (mat. 1689) to the Hall and it would appear that it was Basil Kennett, or more probably his elder son who organised the donations. Four of the donors came from within nine miles of Dymchurch and all from within 30 miles. Moreover, several have demonstrable links to the Kennetts.

White Kennett and Hall Spirit

White Kennett (1660-1728) is one of the most distinguished Aularians of the 17th and 18th century. He was renowned both for his antiquarian and historical studies and his preaching, but his enemies accused him of being an opportunistic careerist.

His ability marked him out from the start of his career in Hall. A biography, The Life of the Right Reverend Dr. White Kennett published in 1730 describes how his tutor Andrew Allam (mat. 1671) “took particular delight in imposing Tasks and Exercises on him, which he [Allam] would often read in the common Room, before the Masters and Gentleman Commoners for an Occasion of commending his pupil.” Allam also set him to translate several Latin works into English, including Erasmus’ In praise of Folly, of which he subsequently arranged for the publication.

Kennett clearly threw himself into life at the Hall, an early example of what we think of today as Hall Spirit. A surviving notebook of his held in the British Library has several long Latin poems addressed both to Allam and to Stephen Penton, the Principal. The apparently organised donation of books is not the only example of his interest in Penton’s project to build and equip a library and a chapel for the Hall.

In the same notebook is a poem ‘On ye building of our Chappele’ exhorting richer Aularians to contribute funds towards the scheme. The poem was recited in the Old Dining Hall on 8 June 1680 or 81 (where in 2022 the current HALLmarks campaign for the new building at Norham St Edmund was also launched). Readers interested in this early example of fundraising campaigning can find out more in the forthcoming issue of the Hall Magazine where the poem appears in full. It should be said though that Kennett’s enthusiasm out runs his skill. It is obvious why he is remembered as a scholar and a preacher, not as a poet.

Ambition clearly formed part of Kennett’s engagement with the Hall. His biography notes his close friendship with the aristocratic ‘Gentleman Commoners’ of the Hall despite him being of the “meanest condition”. After his degree he was ordained and appointed to church livings in the gift of the families of two of his Hall friends, William Glynne (mat. 1679) and Francis Cherry (mat. 1682).

Kennett returned to the Hall as the Vice-Principal in 1691 and served as the University Public Lecturer and Pro-Proctor. He was subsequently a curate at St Botolph’s in London, Archdeacon of Huntingdon and successively Dean then Bishop of Peterborough.

The Kent donors and their books

Looking more closely at the donors and the books they gave gives some insight into both how networks of friendship worked amongstt the clergy and gentry in the Early Modern period and also the kind of books and their subjects that were of use as the Old Library’s collection was first being assembled.

1. Stephanis Bate Rector de Horsmanden

Stephen Bate matriculated at Wadham College in July 1665 aged 16. He became the Rector of Horsmonden in Kent in 1673. He was the nephew of the mathematician and cryptographer John Wallis, who was the Savilian Professor of Geometry at Oxford. In 1696 Bate gave Wallis a manuscript of works by the 15th century theologian Nicholas of Cusa and others which had previously belonged to the Elizabethan astrologer and magus John Dee.

Horsmonden is a little over 30 miles from the Kennetts at Dymchurch, but Bate was originally from Lydd which is only 8 miles away. However, it is John Wallis who serves as a closer connection. According to the Life of White Kennett, it was Wallis who recommended that White Kennett attend the Hall and Thomas Hearne records that Kennett was a protege of his and “sometimes waited on Dr. Wallis to Church with his skarlett, & wt other offices of a menial servt he might do for him I cannot tell.”

There is some confusion over Bate’s donations to the Hall. The donor lists record the gift of three theological books by Church of England divines. However, the inscription in one of the books, Richard Field’s Of the Church (shelf mark Fol. N 3, published London, 1635), gives the donor as Edmund Waller, an Aularian who matriculated in 1663. Moreover an early lending list of the Hall’s books has the volume being borrowed twice in May 1668 so it cannot have been donated by Bate as the Kent books appear to have been given in 1682-1684.

Another, John Selden’s Historie of Tithes (4° B 15, London, 1618), is ascribed to one of the other Kent donors, James Brome, on its endleaf.

On the other hand our copy of De Situ Orbis (4° E 15) by Pomponius Mela, the earliest known Roman geographer, does have an inscription naming Bate, despite the gift not appearing in any listing of donors.

The discrepancies have serval possible explanations. Bate may have given a second duplicate copy of Of the Church which was not retained, for example. Hearne may have been working from incomplete or illegible sources when compiling the list. Another possibility is that Bate gave money rather than physical copies of books with some titles being assigned to the gift as happened with some other 17th century gifts to the Library.

2. Johannes Bate Generosus de Ashford

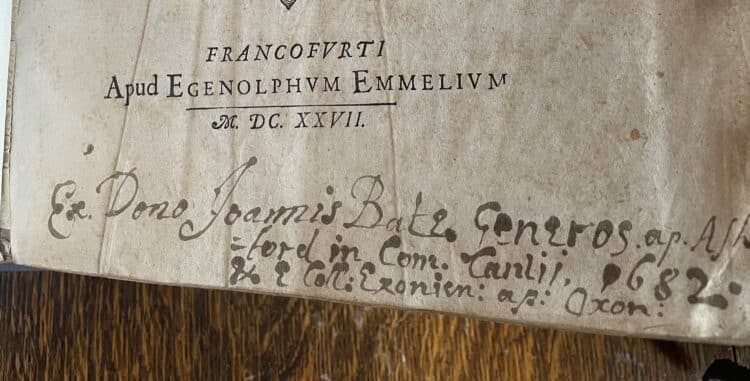

John Bate is described as Generosus, ‘a noble man’ or gentleman but also with something of the modern English sense of ‘generous’. This is the description applied to all of the lay men from the Kent group of donors in both Hearne’s list and in donor inscriptions in some of the books; it is not used anywhere elsewhere in the donor list or in other extant donor inscriptions. Again, suggesting the seven belong together as a group.

John Bate was the son of James Bate of Ashford in Kent, he matriculated at the age of 17 at Exeter College in November 1678. I have been able to discover very little else about him. The coincidence of surname and that Ashford is only a dozen miles from Lydd, suggest he may have been a relative of Stephen Bate (a cousin?) and thus of John Wallis. In that respect it is notable that Exeter was Wallis’s College. Bate was the same age and matriculated the same year as White Kennett and it is easy to infer they were acquaintances.

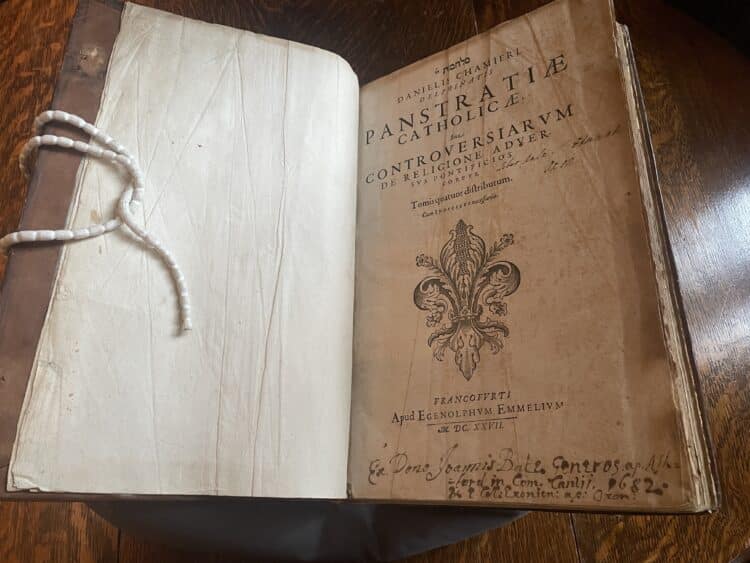

John Bate presented a copy of Panstratiae Catholicae (Fol. C 14, Frankfurt, 1627) by the French Huguenot clergyman Daniel Chamier (1560-1621). The work is a compilation of the doctrinal differences between Protestants and Catholics, particularly in regard to the authority of the Pope. Chamier was a leader of the French Reformed Church, he was involved in the drafting of the edict of Nates which extended limited toleration to France’s Protestants and was also responsible for the insertion of an article into the Reformed Confession of Faith asserting the Pope to be the Antichrist. He was killed by a cannonball when preaching to troops defending the walls of Montebaun when it was besieged by Louis XIII in 1621.

The donor inscription in the records Bates’ gift as being given in 1682. It’s striking that Bate was still a very young man (21 years old) at this point and would just have been coming to the end of his own university career and also that he doesn’t appear to have given any books to his own college, Exeter.

3. Jacobus Broome A:M: Rector de Cheriton

James Brome was born in Cambridge in 1651 or 1652. He attended Christ’s College there before being ordained and appointed to the parishes of Newington (1674) and Cheriton (1679) in Kent.

In 1693 he published an edition of a Treatise of the Roman Ports and Forts in Kent which had been left in manuscript by the antiquary William Somner at his death in 1669. The Life of White Kennett credits Kennett as the inspiration for this edition, encouraging Brome, who had shown him the manuscript to publish it to “do some Honor and Service to his Native County of Kent.” Kennett collaborated with Brome, writing a life of William Somner to accompany the text. Brome went on to publish Travels over England, Scotland and Wales in 1700, although the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography notes rather sardonically that “it seems unlikely however that Brome had ever ventured far beyond his own library…”

Brome is credited with three donations to the Hall (plus the copy of Selden’s Historie of Tithes mentioned above which the list ascribes to Stephen Bate but the inscription in the book to Brome). Of these we still hold one, a copy of Baconiana. Or Certain genuine remains of Sr. Francis Bacon (4° A 3,London, 1679), an edition of some of Bacon’s works which were published posthumously. Notably this was essentially a new book when given and seems to have found an early and enthusiastic readership in Hall – Thomas Colericke (mat. 1687) a student who began his studies shortly after the donation has scrawled his name on the title page just above the donor inscription.

Another of Brome’s gifts is just described as “2 sermons”, it is very tempting to think this might have been two of Brome’s own sermons which were published together as The Famine of the Word Threatened to Israel and God’s Call to Weeping and to Mourning. There is no trace of this work in any early catalogue of the Library and it seems to have suffered a fate which often befalls unsolicited, self-published works.

Also lost is a two-volume edition of the works of the satirical Greek poet Lucian. This appears to have been lost early, it is marked Desidererantur (‘wanted’ ie missing) in a later version the donor list compiled by Hearne c.1701-2.

4. Franciscus Peck Rector de Saltwood

Francis Peck was originally from London. He was admitted to Pembroke College, Cambridge in July 1667. He became Rector of Saltwood in Kent in 1674, serving until his death in 1705. He was a friend of White Kennett and copies of their correspondence survives amongst Kennett’s papers in the British Library. These include letters they exchanged in at the start of 1689 when both were dealing with the aftermath of the revolution of 1688 which had installed William and Mary on the throne and were wrestling with its implications for the oath of allegiance they had sworn to the deposed James II.

Peck gave the Hall a copy of John Pearson’s Exposition on the Creed (Fol. N 20, London, 1669). Pearson (1613-1686), who served as Lady Margaret’s Professor of Divinity at Cambridge and Bishop of Chester, was one of most erudite Anglican theologians of the 17th century. The Exposition is a very influential examination of the Apostle’s Creed – the statement of faith still recited every week in Evensong in Chapel. As such it was an incredibly useful gift to the Hall where most students were hoping to become Church of England Clergy. The book shows one sign of being used across the centuries of its being with us: on one of the endpapers an early 19th century reader has doodled a sketch of a clergyman holding a baby for baptism.

5. Tho: Tolson generosus de Beakston

Thomas Tolson was a lawyer originally from Windsor. He attended The Queens College, Oxford (mat. 1654) before going on to Gray’s Inn and being called to the bar in 1663. The same year he married Elizabeth Roberts of Beaksborne in Kent, where he settled. Tolston has one of the clearest ties to White Kennett and his family. White Kennett lived for a year with the Tolsons in Beaksborne while recovering from smallpox before he went up to Oxford. He acted as tutor to Tolson’s three sons “with great content and success” according to The Life of Dr White Kennett.

Tolson’s gift to the Hall Library was a handsome one – a Latin edition of Sebastian Münster’s Cosmographia Universalis (Fol. G 4, Basel, 1550).The Cosmographia is a wide-ranging and beautifully illustrated work both containing realistic renderings of cities in Europe and also fantastical and grotesque illustrations of sea monsters to be found off the coast of Greenland and monopods and men with heads in their chests in the section on Asia.

The Cosmographia was the first geographical work written in German. It was immensely successful going through 19 editions between 1544 and 1628. It was also translated into several other languages. It is frequently a star of our exhibitions and our outreach sessions with school students.

Tolson’s donation is recorded in the book as being in 1684. This means the books from Kent arrived in at least two tranches; this may reflect multiple trips by White Kennett from Oxford to his home or perhaps successive donations organised to celebrate his graduation as a BA (on 2 May 1672) and an MA (22 January 1685).

6. Timotheus Bedingfeild generosus

Timothy Bedingfield was a parishioner of Basil Kennett’s at Dymchurch. He died in 1693 and his memorial survives in the church of Saint Peter and St Paul there. On it he is described as ‘captain’; so presumably had followed a military career.

His gift to the Hall is not the only educational benefaction he made. The memorial records his bequeathing of land in Kent to establish a fund “towards the education maintenance an bring up of such poor… children of … poor parents,,,”. The recipients are to be sent to “…one of the Universities of Oxford or of Cambridge if capable…”. The Bedingfield Educational Endowment still exists and currently awards a small cup annually to the pupil “making the most educational progress in the year” in three local primary schools.

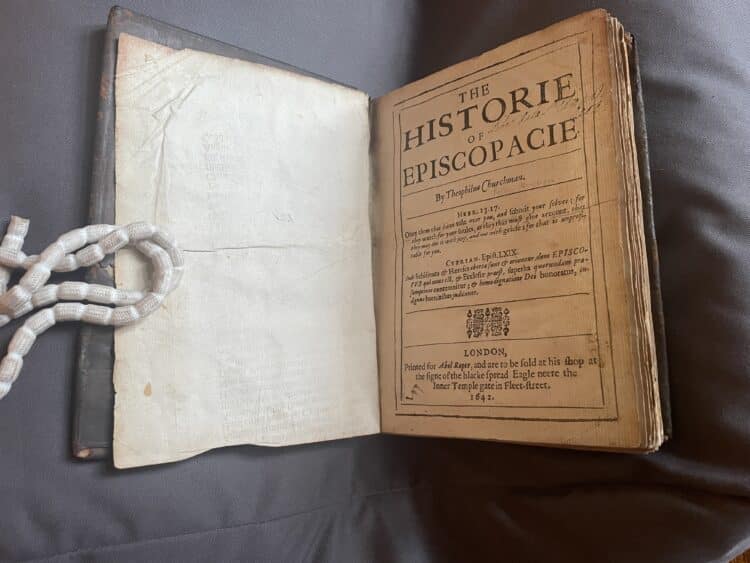

Bedingfield’s gift to the Hall was a copy of The historie of episcopacie (4° B 4, London, 1642) a work defending the traditional ecclesiastical hierarchy published during the gathering set of crises that led up to the Civil war by the ardent Royalist Peter Heylyn (1599-1662) under the colourful pseudonym ‘Theophilus Churchman’.

7. Basileus Kennett A:M: Rector de Dimchurch

Basil Kennett had an unusual path to a clerical career. He was borne in Folkestone to a merchant family. He does not appear to have attended university (despite the MA that he is given in Hearne’s donor list). At the time of White’s birth in 1660 he was a storekeeper in the naval dockyards at Dover. He was ordained at some point in the 1660s and received his first parish, Postling a village north of Folkestone, in 1668 and was appointed to Dymchurch in 1676. Both of his sons attended St Edmund Hall. Basil (mat. 1689), his second son, went onto a distinguished academic career as a Fellow and ultimately President of Corpus Christi College.

Basil Kennett’s donation to the Hall Library is the largest and the most impressive – four folio volumes of works by major theological authors: St Jerome, St Bernard of Clairvaux, St Hilary of Poitiers and the church historian Eusebius of Caesaria. Two of the books the Works of St Bernard (Fol. G 1, Paris, 1508) and the Letters of St Jerome (Fol. G 2, Lyons, 1508) are particularly fine volumes with beautiful woodcut illustrations. At the time of their donation they were the oldest works held by the Library. Surprisingly none of the four volumes have donation inscriptions and without Hearne’s list, Basil Kennett’s contribution to our collections would be unknown.

Celebrating Benefactors

This weekend as we celebrate not only St Edmund but also the Hall’s many benefactors, the books donated by the Kennetts and their friends will be on display together in the Old Library for the first time. We will be open on the afternoons of Sunday 16 and Monday 17 November, please do come and visit if you can. If you can’t come this weekend, we are always happy to show off the Old Library to Aularians and their friends and families, just get in touch at library@seh.ox.ac.uk.

Category: Library, Arts & Archives

Author

James

Howarth

James has been St Edmund Hall’s Librarian since May 2018. He is responsible for maintaining and developing the library’s collections – including the historic and special collections that are housed in the seventeenth-century Old Library and is keen to promote their use in research, study and outreach.