‘The same Sad Calamyties’: Oxford in a time of Plague

2 Jun 2020|James Howarth

- Library, Arts & Archives

One of the things about being a more than 700-year-old institution, as Teddy Hall is, is that we have faced many trials before. This is not the first time the Hall and the University have had to cope with the effects of a deadly pandemic. On the day I left Oxford as the lockdown began I passed the church of St Michael at the North Gate on Cornmarket and someone had posted a sign on the door reading ‘We were here during the Black Death in 1347 and we were here during the Great Plague in 1665.’

The vivid account of the 1665 plague in London in Daniel Defoe’s Journal of a Plague Year and the parallels and differences from our experiences now have been much commented on recently (it’s also the Guardian online book club reading choice for this month). Defoe’s work is fiction written over fifty years after the event, but in surviving diaries, letters, official documents written at the time we can gain some insight into what being in Oxford in 1665 during the plague was like.

‘A blazing starr seen’: Portents and rumours

On 18 December 1664 at about 6pm the Oxford antiquarian Anthony Wood saw a ‘blazing starr’ as he walked home along Botley causeway from a pub in Cumnor.

This he afterwards decided was a sign of things to come:

“In the next yeare followed a great plague in England, prodigious births, great inundations and frosts, warr with the Dutch, sudden deaths, particularly in Oxon…”

Throughout the first part of 1665 he recorded in his diaries a series of ominous signs: earthquakes in Oxfordshire in January, ‘the devill let loose to possess people’ and a monstrous child born in the parish of St Magdalen in Oxford with ‘one hand, one leg, one eye in the forehead, noe nose, and its 2 eares in the nape of the necke.’

However on the 23 April more concrete bad news emerged as the first reports of plague in London reached Oxford (interestingly this a full week before Samuel Pepys first mentions it in in his diary).

The first direct effects of the outbreak were not felt in Oxford until the summer when ‘the Act,’ the forerunner to today’s Encaenia ceremony, was cancelled (as this year’s has been). The event attracted many visitors from outside Oxford and the worry was some would bring the infection. Wood reports that the decision was quietly welcomed by some scholars who took the opportunity to take their degrees without public disputations and the ‘expenses of the customary entertainments.’

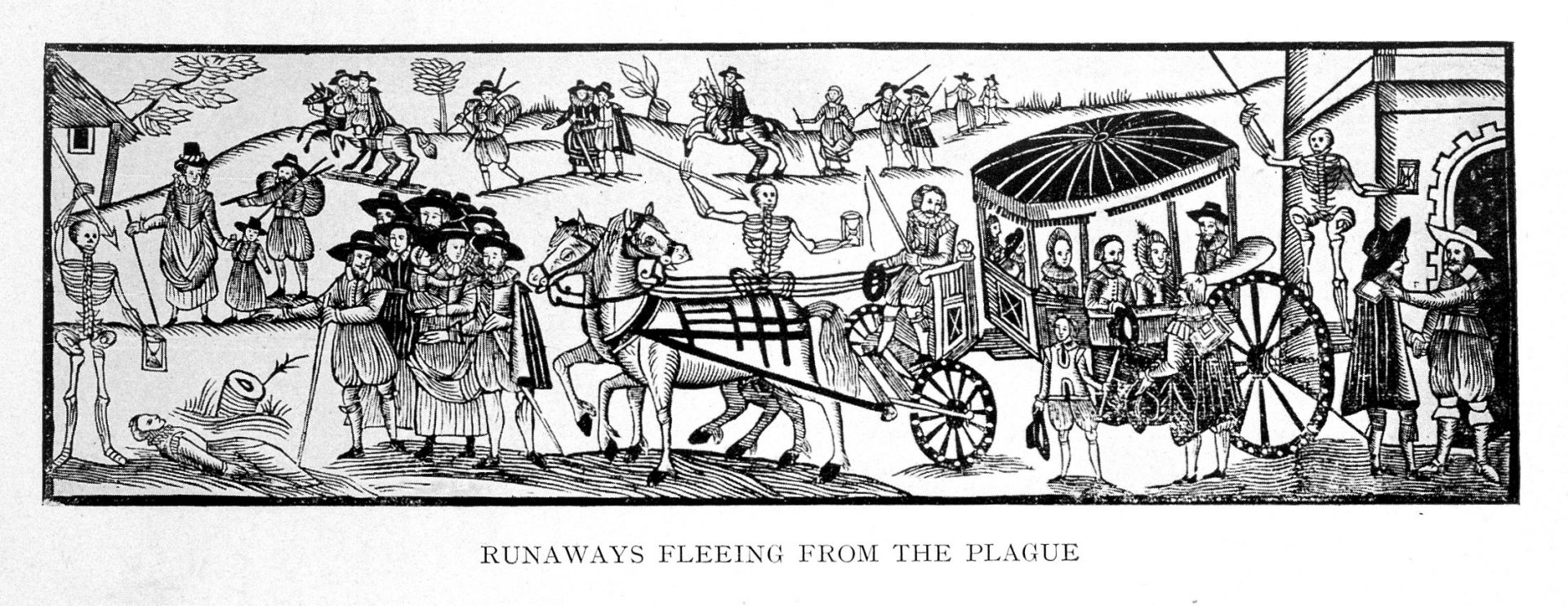

Fear of contagion was the driving force behind the guard that was set at night from early July in Oxford to keep out refugees from London. Rather ghoulishly, students would gather at the entrances to the city to watch.

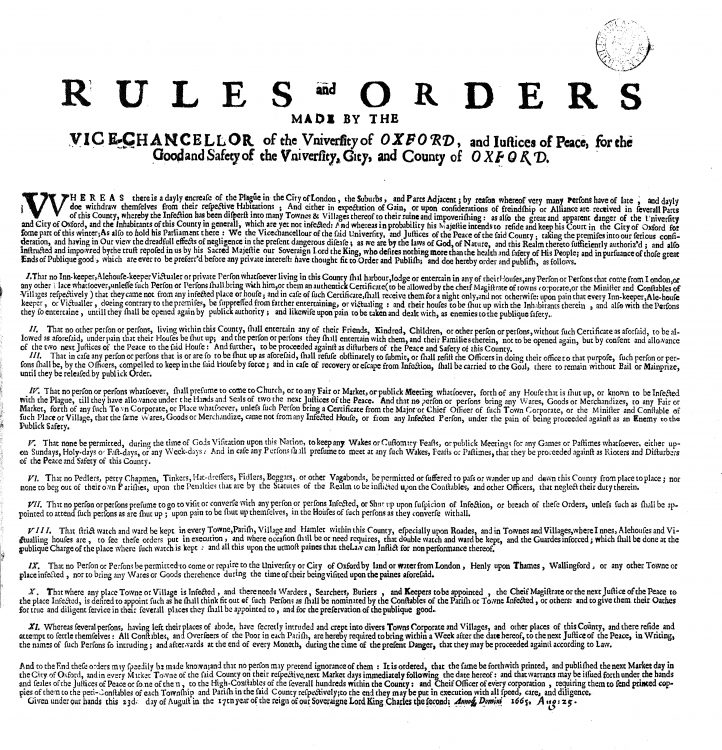

Stronger regulation was in imposed on the 23 August when the Vice-Chancellor and the local authorities, in a rare show of town and gown unity, issued ‘Rules and orders… for the Good and Safety of the University, City and County of Oxford.’ Public gatherings were banned. Citizens were not permitted to receive or even goods from the capital without an ‘authentike certificate’ of health issued by a public figure. Those breaking the rules were liable to be shut up in their houses until the threat of infection had passed.

‘Vaine, beastly and carelesse’: the Court comes to Oxford

However not all visitors could be refused. Charles II and his court had fled Westminster for Salisbury earlier in the summer, but the plague caught up with them there and in September the court prepared to move to Oxford.

First, Charles’ chief minister the Earl of Clarendon, who was also the Chancellor of University, arrived to make arrangements and was received by the Vice-Chancellors and the Heads of House with suitable pomp. The council also made preparations, The veteran local politician Sir Sampson White (whose son Francis is honoured on the benefaction board in the Teddy Hall Library), having been Mayor at the Restoration was pressed into service again ‘at this time of weighty causes’, despite his offer of £10 to be spared the burden. The city and the University each contributed towards the building of huts outside the city to house anyone sick with the plague. The council also established a committee to consider the crucial matter of a gift for the King and Queen.

Charles and his brother the Duke of York (the future James II) arrived on 25 September, followed the next day by the Queen, Catherine of Braganza. As when Oxford had served as the royalist capital for Charles I during the Civil War in the 1640s the court took up their abode in various Colleges. The King and his ministers were at Christ Church, the Queen and her ladies-in-waiting at Merton, other officials elsewhere. For example the Bishop Salisbury, John Earle, was lodging at Univ when he died in November (not of the plague) despite having previously been a Fellow of Merton.

The transfer of the court also meant the arrival of the whole diplomatic corps. Magdalen became the French embassy, New College the Spanish. It’s here we first catch a glimpse of someone with an Aularian connection. Stephen Penton, afterwards Principal of St Edmund Hall (1676-1684) but at this point a Fellow of New, gave the Latin speech welcoming Count of Molina, the Spanish Ambassador. Wood reports that the Ambassador replied in equally fluent Latin.

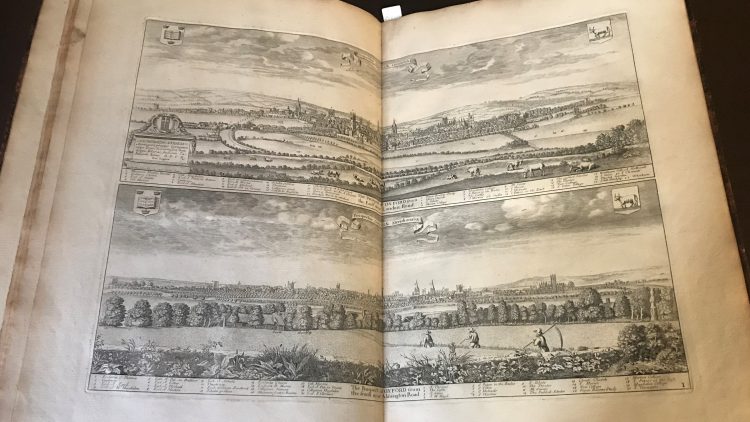

Disruptions: Government

State papers in the National Archives record the efforts of Joseph Williamson, the Under Secretary of State, to keep the wheels of government turning and the court safe. Post from elsewhere in the kingdom was diverted at great expense to reach Oxford without first passing through London and risking plague. Likewise, barges bearing goods from the capital were stopped at Abingdon to prevent any danger to the Kings health. Another record records a certificate of health given to a servant of Molina’s to recover the Ambassador’s possessions from the Spanish Embassy where they had been left in the hasty flight from the capital.

Courtiers were reluctant to handle newspapers from London so from 7 November an official publication, the Oxford Gazette was issued with news and information. Renamed the London Gazette when the court returned, it remains in print today and has a claim to be the longest continually published newspaper.

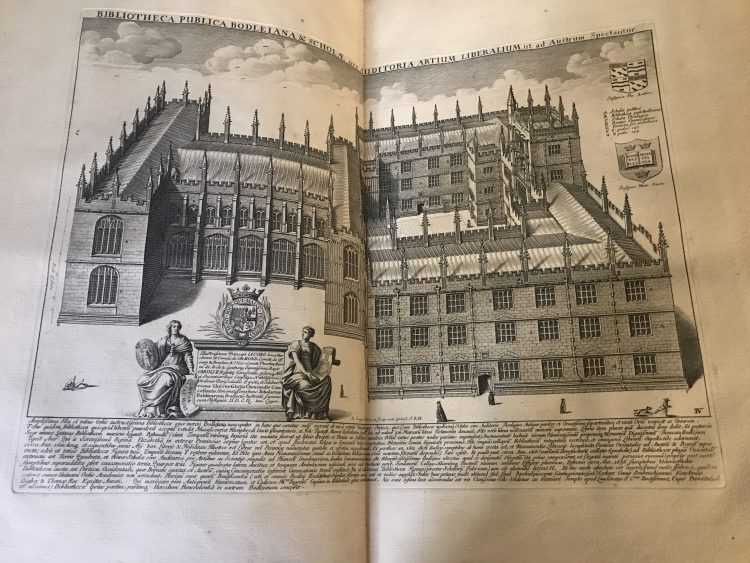

The government’s finances, not least the ongoing war with the Dutch, necessitated the summoning of Parliament to Oxford in October. The Bodleian was turned over to their use. The House of Lords sat in the Geometry school and the Commons in the Convocation House, committees met in the Divinity School. Some MPs did take advantage of their new location. The poet Andrew Marvell who was MP for Hull was granted a reader’s ticket to the Library while he was in Oxford. As well as funds for the Crown, Parliament passed controls on the importation of cattle to help prevent the transmission of plague (only slightly undermined by large exemptions for the Royal Family), taking advantage of their presence in a Royalist bastion, strict measures against puritan ministers who been dismissed from the posts. The University’s Stuart loyalty was also reflected in the manner in which the Commons expressed its thanks, a vote of appreciation for Oxford’s resistance to the Commonwealth in the 1650s.

After Parliament was prorogued at the end of October, it was succeeded by the Law Courts who took up residency in the schools with the Lord Chief Justice presiding in the History School.

Disruptions: The University

What was the effect of the court’s intrusion on the University? There is evidence that, displaced from their rooms and in fear of the plague, academics voted with their feet. The Balliol fellow Nicholas Crouch kept a diary in the 1660s with very sparse entries, but he did record his presence or absence in Oxford and he seems to have been away for almost the entirety of the Court’s presence in Oxford. The Principal of St Edmund Hall, Thomas Tullie, appears to have been absent until near the end of December 1665, perhaps in his parish of Grittleton in Wiltshire.

We know of Tullie’s absence thanks to a letter he sent Joseph Williamson when he returned. They had both been Fellows of Queens and Williamson was a benefactor of both his old college and of Tullie, whose appointment as Dean of Ripon he helped secured in 1675. The letter shows that having important friends so close at hand was not necessarily for the best. Tullie apologises abjectly for not having seen his friend and also for some misunderstanding concerning affairs at Queens and hopes to wait upon him at his soonest convenience.

The plague and the arrival of the court also affected student numbers. For example, neither Balliol nor Brasenose recorded any matriculations during Michaelmas term 1665 and there were only five admissions at Teddy Hall, down from ten the year before (and perhaps significantly only two students appear to have matriculated). It should be noted that in this period students often arrived in the spring and summer rather than at the formal start of the academic year. Although again the Hall recorded only three admissions in May-July 1665 against eight in 1664.

Disruptions: Scandal

The presence of the court in Oxford disrupted the said life of the University. Anthony Wood was scathing in his description of their presence:

“The greater sort of the courtiers were high, proud, insolent, and looked upon scolars noe more then pedants, or pedagogicall persons…To give a further character of the court, they, though they were neat and gay in their apparell, yet they were very nasty and beastly… Rude, rough, whoremongers; vaine, empty, carelesse.”

Several events gave rise to great scandal. The Duchess of York was said to have fallen in love with her Master of Horse who had to be sent away in December. At the end of the month, the King’s mistress, the Countess of Castelmaine, gave birth to his illegitimate son (her third by Charles). She was lodging in Merton because of her position as a Lady of the Bedchamber to the Queen who was also pregnant. An outraged but anonymous Merton Fellow pinned an obscene verse in Latin and English to her door. Despite a reward of £1000 he was not identified. The hangers-on at court also caused problems, Wood describes a ‘Major Clancie’, dressed in a ‘red coat with silver buttons, looked sharkingly’ and would steal coats and cloaks during church services,

News of the scandals reached Pepys in London and contrast strongly with his description of London during the plague:

“But Lord, how empty the streets are, and melancholy, so many poor sick people in the streets, full of sores, and so many sad stories overheard as I walk, everybody talking of this dead, and that man sick, and so many in this place, and so many in that. And they tell me that in Westminster there is never a physitian, and but one apothecary left, all being dead – but that there are great hopes of a great decrease this week. God send it.”

‘Yet Oxford escaped scot fre’: Aftermath

Wood’s outrage at the presence of the king and court was not just moral, the coming and going of government, parliament and the courts put Oxford at grave risk from the plague.

“In the King’s suffering the parliament and terme to be kept here, it was noe better then tempting God to bring upon us the sad judgment of the plague.”

Yet miraculously the plague did not come and slowly life returned to normal. The King departed for Hampton Court on 27 January. The Queen tragically gave birth to a still-born child at Merton at the start of February and left shortly afterward.

‘After the court was gone, Oxford being fre of the plague, the scolars returned; and hundreds more came, more then before’ reports Wood. Admissions at Oxford in 1666 also benefited from an outbreak of plague in Cambridge.

The returning dons did face one last unpleasant gift from their guests who had left ‘at their departure their excrements in every corner, in chimneys, studies, colehouses, cellers.’ (This was more recently memorably described in the BBC’s Horrible Histories)

But even without the plague life in Restoration Oxford was hard. In March 1666 Wood records the death of a Teddy Hall student, Edward Parez, from small pox which was then rife in the city. He was 19. Edward was buried in St-Peter-in- East, now our Library, and a silver plate he gave when he arrived in 1663 was one of those sold to help fund the construction of the Chapel and the Old Library in 1680 .

A happier note to end on is provided by Count of Molina. When the Spanish Ambassador left New College at the start of February, he gave a speech thanking Stephen Penton for his welcoming speech and the Warden and Fellows for their hospitality. Molina said he had sent a copy of it to the college he had founded at the University of Salamanca. And having been so long at the College that he considered himself a fellow, so New College could consider itself to have founded colleges in both Oxford (Magadalen College’s founder William Wayneflete was an alumni of New College) and in Spain and any New College scholar visiting Spain would receive hospitality at his college. I think this image of hospitality and care to those trapped by plague and of international and especially academic cooperation are fitting ideals to remember right now.

Category: Library, Arts & Archives

Author

James

Howarth

James has been St Edmund Hall’s Librarian since May 2018. He is responsible for maintaining and developing the library’s collections – including the historic and special collections that are housed in the seventeenth-century Old Library and is keen to promote their use in research, study and outreach.