Rousseauville

6 Mar 2019|Karma Nabulsi

- Research

In 2005, when I had the pleasure of taking up the position of Fellow and Tutor in Politics at the Hall, the first thing I carried to my new office, climbing up the stairs to the top of the Library Tower, was a portrait of my subject of scholarly study, the philosopher Jean-Jacques Rousseau. It now hangs above the mini-fridge.

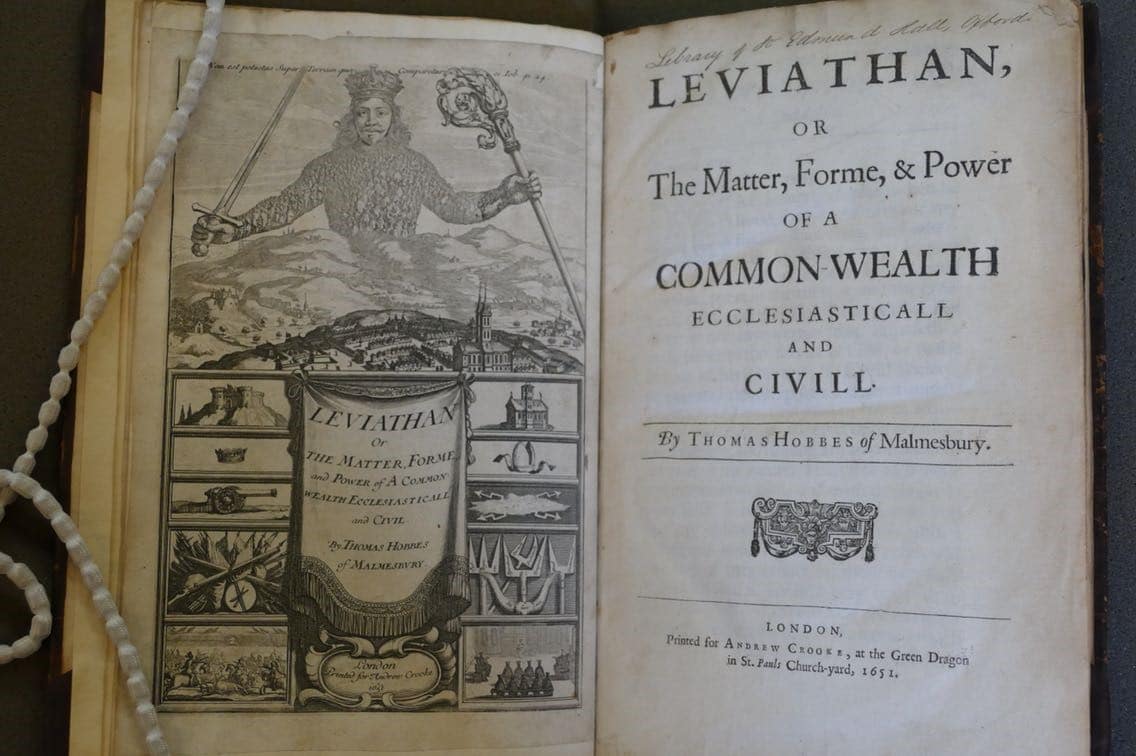

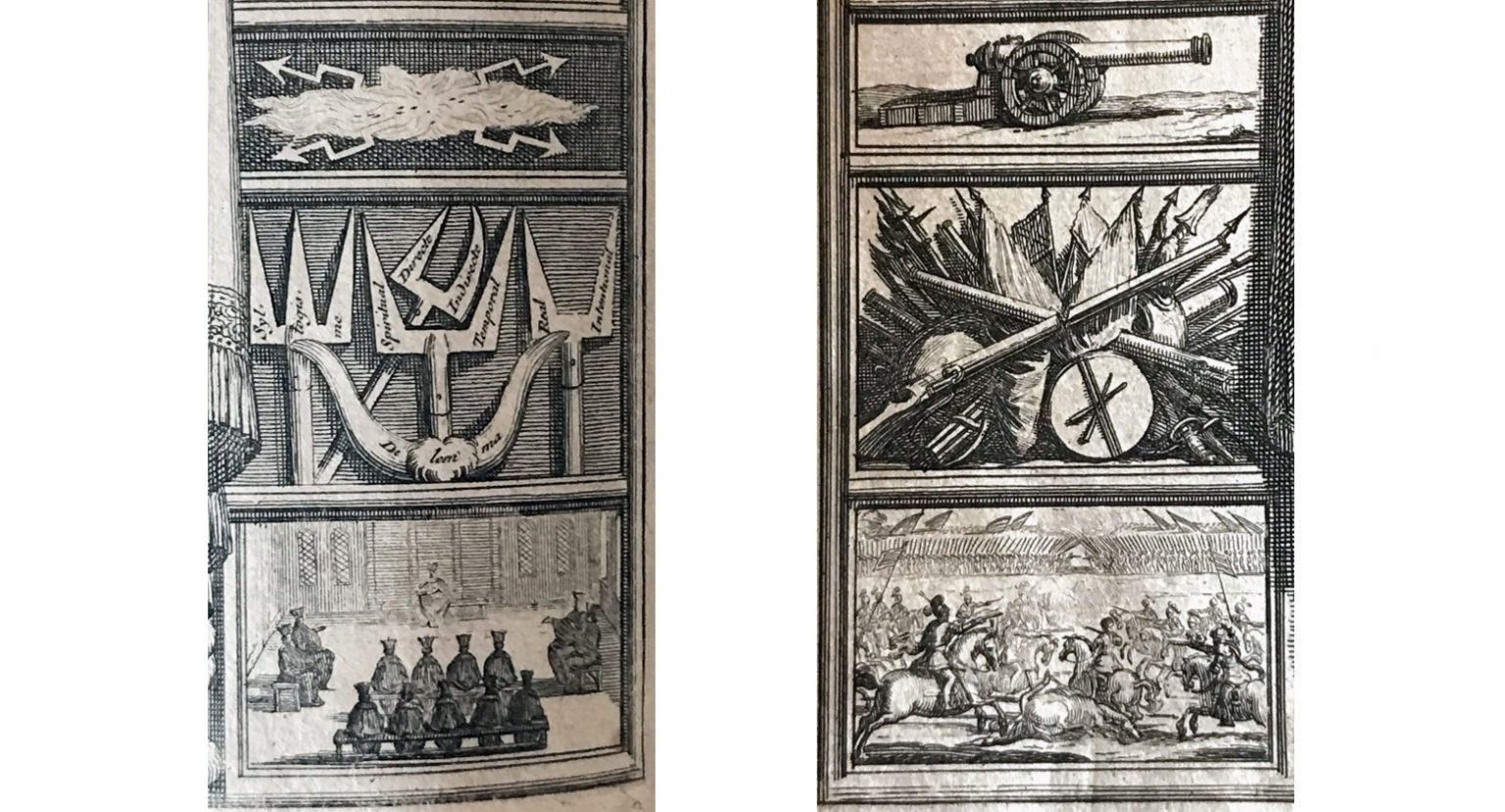

With the centenary of Modern Greats around the corner in 2020, one could say that Jean-Jacques Rousseau (also known as ‘The Man’) was the quintessential PPEist, easily combining the three disciplines across a remarkable oeuvre. Claude Lévi-Strauss claimed him as founder of his emerging discipline of anthropology, whilst lesser scholars and disciplines preferred to demonise him, instituting a phenomenal black legend. Although Oxford can quite often feel like Hobbestown to busy academics under attack from the committee structure (our 1651 copy of the Leviathan in the Old Library’s collection catches this sensibility well), Oxford is in fact a quintessentially Rousseauiste place. Not that this makes it an easier social contract to uphold.

Oxford belongs to Rousseau, because he is all about participatory democracy: the principle that we can free ourselves by obeying rules that we ourselves fashion, together. The notion that self-governance, in college committees and governing bodies across town, in junior, middle, and senior common rooms, at the university’s Congregation and multiplying institutions, can be imagined as freedom will appear a cruel and gruesome joke to colleagues landing in 8th week of Hilary term.

The onerous nature of discussing, consulting, listening, and deciding matters together, after carefully ensuring inclusion of each participant with equal respect, had Rousseau describing the practice, as sketched out in his Social Contract as “sheer lunacy”; naturally this work kicks off our first year Politics Prelims discussions. The founding principle of democracy that Rousseau gifted to modern society – from liberal democracies to republics the world over – also plays out through my past and current research initiatives and public contributions. Its central premise: that sovereign power is vested in the people not the king; that the only legitimate rule is one of the people themselves; that all political institutions must be the outcome of their determining and their decisions; that popular sovereignty is the very source of legitimacy, is such a radical concept that it needs to be refreshed, renewed, and reintroduced – sometimes on a daily basis.

Indeed its requirements as often locates me in a meeting as at my desk, where I am meant to be working on my next book, or writing the chapter commissioned for the Oxford Handbook on Rousseau, on the promising subject of ‘Emancipation’. Being on two terms’ leave, which is a freedom I am particularly well suited for, is the reward (if one were needed) for three and a half years of servitude (or freedom, as Rousseau would have it) in the role of director of undergraduate studies (DUS) of our Department of Politics and International Relations, the latter a freedom I never got the hang of.

When in post, a commitment to the benefits of participatory democracy found me initiating a Department-wide curriculum diversity review for our core Politics papers by involving the entire teaching faculty in the process. It included students who took the first-year and FHS papers. Their shiny presence as well as their intellectual contributions proved invaluable to its success: the engine of change here at Oxford are our students, and the more we see of them in our decision making, the freer we become (in the classical republican sense).

Instead of endless meetings, I could free myself to write the keynote lecture I was invited to deliver at the Refugee Studies Centre’s biennial conference later this month, on the theme of “Democratising Displacement”. The topic of the lecture will be on some work I had the fortune to design and direct a few years ago, to afford refugees a voice in the decision-making of their body politic, based on the simple and inclusive principles of Rousseau’s Social Contract. Working with the UN, the UNHCR, UNRWA, national and regional central election commissions and experts, the initiative established an online voter registration, accompanied by a civic registration drive, plus the creation of a robust and secure state-of-the-art electronic voting mechanism (aka ‘the Magic Machine’), that was kindly developed by colleagues Gavin Lowe and Bernard Sufrin here at Oxford.

The project was undertaken so that refugees could participate in their national civic and political life in whatever place, predicament, and condition luck had placed them, to use their inalienable freedoms to build a common, democratic future together.

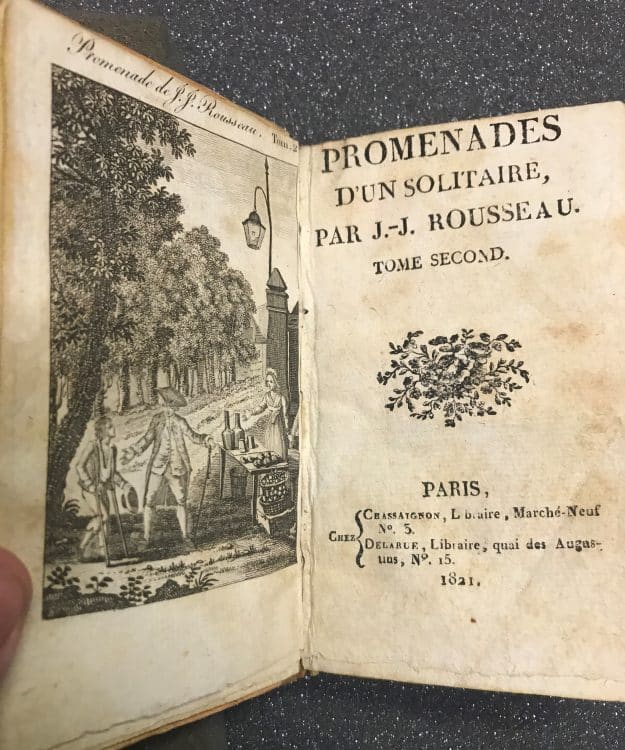

In his autobiography Rousseau remarks on a transformative moment in his life when, so struck by his own thoughts that he had to sit down under a tree, he suddenly realises that “everything, everything, is radically dependent on politics”. It is one of the reasons Rousseau remains so fresh and relevant to the current generation of students, and why he remains so to me, in my world resting at the intersection of political philosophy and political practice.

Read more on our blog

Category: Research

Author

Karma

Nabulsi

Professor Karma Nabulsi is a Senior Research Fellow at St Edmund Hall. Her research is on 18th- and 19th-century political thought, the laws of war, and the contemporary history and politics of Palestinian refugees and representation.