Harrowing of Hell

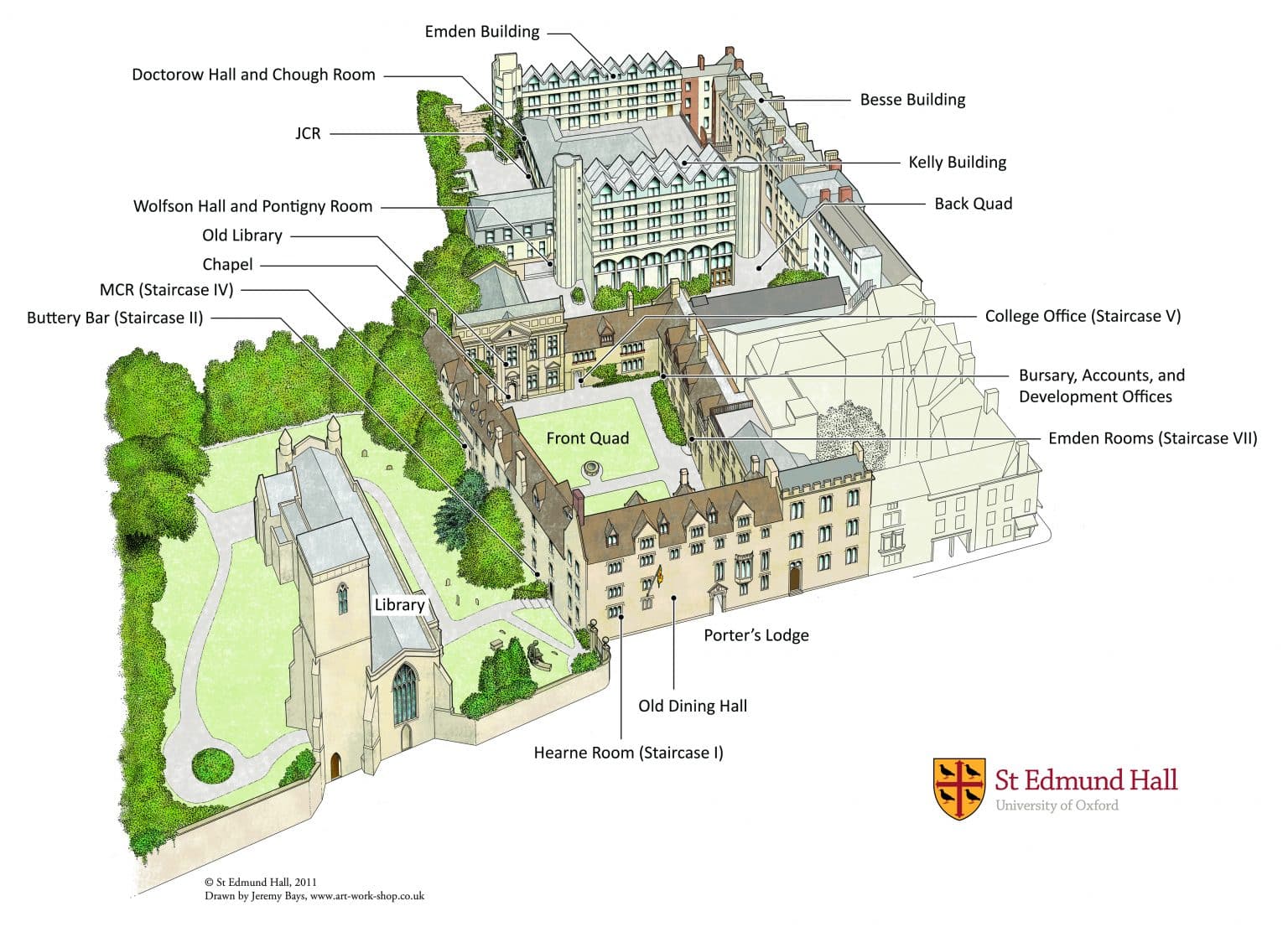

- Location: in the garden to the east of St Peter-in-the-East

- Time: 3:30pm

- Performers: Medieval Germanists

Cast

Lucifer – Linus Ubl

Jhesus – Alex Peplow

Sathanas – Mai-Britt Wiechmann

Adam – Alyssa Steiner

Eua – Jens Müller

Angeli – St Edmund Hall Choir

Animae – Sam Dunnett, Andrea Huber, Christoph Huber, Xuhui Zhang, Marie Zöckler et al.

Costumes – Mai-Britt Wiechmann and Natascha Domeisen

Behind the scenes helpers – Anna Branford and Tiziana Imstepf

Summary of the Play

The Harrowing of Hell is a dramatic interpretation of Christ’s storming of hell to release all the souls of the faithful, going back to Adam and Eve. The scene starts with the angels approaching hell, getting into a dramatic dialogue with Lucifer who tries in vain to keep the souls behind locked gates. Christ triumphs and takes Adam and Eve with him. To refill the empty space, Lucifer then sends out Satanas to capture new souls for him from amongst the contemporary audience (watch out!), each of whom have to confess their faults before being locked up.

Text

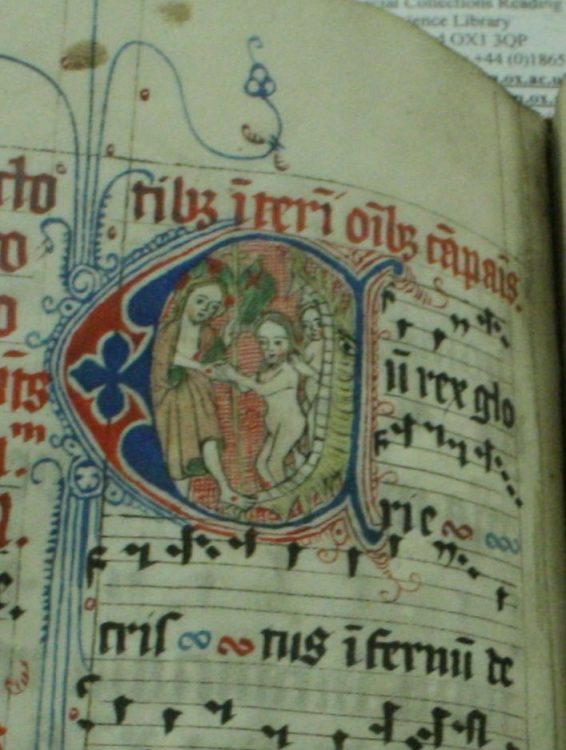

Read as a PDF the Middle High German text (together with an English translation) of the play, from Das Innsbrucker Osterspiel.

Text extract ‘Harrowing of Hell’ from Das Innsbrucker Osterspiel

Based on the digital version by Nigel F. Palmer / Henrike Lähnemann of Das Drama des Mittelalters. Mit Einleitungen und Anmerkungen, ed. Eduard Hartl. Vol. 2: Osterspiele, Leipzig 1937 (DLE. Reihe Drama des Mittelalters 2), p. 136-189

Translation: Alexander Peplow / Henrike Lähnemann

Angels: (singing) ‘Lift up your gates, princes, and be lifted up, eternal gates, and the King of Glory will enter in.’ [Psalm 23(Vulgate), used as antiphon for advent]

Lucifer: ‘Who is this King of Glory?’

Angels: ‘Lift up your gates, princes, and be lifted up, eternal gates, and the King of Glory will enter in.’

Lucifer: ‘Who is this King of Glory?’

Jesus: (speaking) You Lords of darkness, your brawling is completely fruitless. Lift up the gates at once – the King of Glory is outside!

Lucifer: Push the bolt across the door, the King of Glory is outside! He shouts right into our ears! Truly, he can rage as much as he can shout! What business has he here? Quickly tell him to go away, else a great storm will force its way through! Give me the pitch-fork and hook, I will drag him into Hell!

Jesus breaks open the underworld.

Jesus: Now come, my very dear children, you who have come from my Father! You shall possess with me forever my Father’s kingdom.

Adam: Joy to me today and ever more! Joy to me for this happy tale! I see him who created me, and through whom Heaven and Earth stand. You are welcome, dear father Jesus Christ! Ah, how long have you been, that it seemed you would never have mercy on us very sorrowful souls! Have mercy on me today, very dear Lord, this I beg of you!

Jesus: Ah, my dear Adam, how did this happen to you? Who gave you the evil advice that you broke God’s command?

Adam: Dear Lord, I’ll tell you: the lying Devil has deceived us. He came to Eve in the form of a snake, and he said ‘This is the best food – you should eat it, then you will become wise.’

Eve: When I grasped the apple from the tree where it hung, at once the curse which still hangs over women was laid: now many souls must suffer pain and sorrow in the fire of Hell.

Jesus: Now come, my very dear children, you who have come from my Father, to my Father’s kingdom, which has been prepared for you eternally!

(singing) ‘Come, you blessed of my Father’ [Matt. 25:34]

Then an unhappy soul tries to leave with God.

Lucifer: No, no, you wicked one, I won’t let you escape!

The Soul: Oh, oh, oh, the Devil has caused me such suffering! Jesus, dear Lord, shall I not go with you from this place?

Lucifer: Oh, oh, pride, that you ever were invented! I was an angel pure and bright, shining above all the host of angels. I had the pride to think that I was destined to sit higher than the true God, who is the highest councillor; I was brought to this by my pride that I was pushed down very deep to Hell, me, and all my companions. Woe to him who engages in pride! It will all be taken out on his soul. All those are doomed to great suffering: woe to them who act in pride!

Then Lucifer runs to his palace, calling out in a loud voice:

Friends, all you dear friends, come with great clamour and take note of my cries, and what I want to say to you: we were powerful for a long time. We fared badly, we have the lost souls, this should make all of you angry! Now catch what you can, let them not escape! Those must be with us for ever, and cannot be saved: Jesus, the great Lord, can hinder us no more!

Satan: Lucifer, dear lord, your humiliation angers me greatly! We won’t rest day or night unless we have fulfilled your will, and I will always work to bring you many souls.

Lucifer: Satan, Satan, my very dear companion, hurry from here to Apulia, so that we can fill Hell!

Satan: Lucifer, my very dear lord, whatever you want, it shall be!

Lucifer: Satan, Satan, my very dear companion, hurry from here to Avignon, bring together for me the Pope and the cardinals, patriarchs and legates, who give people bad advice, king and emperor, bring to me here together, the counts and princes,(they should not find this place amusing), knights and squires (to me they are equally welcome), bring me the squire and the councillor who have done many wrongs to the people, bring me also the usurer (they are absolutely hated by God), the judge with their judgement bring me here on your rope, the priest with the papers, the monks with their tonsures, bring me the publican (whom I want to drown in Hell), bring me the baker with the roll (whom I will prepare into a tasty meal), the butcher with the cow and the weaver as well, bring me also the carpenter, my very dear companion, bring me the cobbler with his awl, the leatherworker with the sole, bring me also the beer-carriers, and the messenger, the glutton, coward, spur-maker, scold, shield-maker, joiner, drinker, gambler, game-player – all those bring me, do what I want as quickly as possible!

Bring me also the drunkard (God may never look on their life favourably), bring me the miller with his girl (whom I will put hindmost in Hell), bring me also the bather with the sponge, den salt-seller with the measure, the smith with the tongues (about which I had forgotten for a long time), the fisherman with the nets, the sailor with the boat, bring the piper and the harpist, the drummer and the fiddler, and all types of entertainers (I cannot name all of them to you), bring me also the woman who spins (with whom I will have fun), also bring me the wool-carder, the brush-maker, bring me also the gossip-lovers who sit on their high places and think themselves to be as holy as the priest’s pig. I know one group, however, which is not right for Hell, which you shall not bring here – then you do well my wishes!

Satan: Lucifer, my dear master, what you demand shall be fulfilled! I will delay no longer – I will set off immediately.

Angels: (singing) Silence!

Then Satan, dragging many souls, says.

Satan: Lord, I have taken care of it well and have brought you many souls.

Lucifer: For this I shall always be thankful, my dear friend!

First Soul: Have mercy, lord Lucifer! I was a poor baker; when the dough got too big, I broke a piece off and mixed it in with the bran. Because of that, I must go to Hell.

Second Soul: Have mercy, lord Lucifer! I was a poor cobbler; I put poor-quality soles on people’s shoes (that wasn’t right to do) and swore they were just as good. Because of that, I must be sent to the Hell fire.

Third Soul: I was a poor chaplain; I did not act well in that role. When I heard the bells ring, I had a special urge: to spend my time with two beautiful women. As soon as one escaped me, I grabbed the other one.

Fourth Soul: Have mercy, lord Lucifer! I was a poor barman: I poured out short measures, and because of that I must spend eternity in tears.

Fifth Soul: Have mercy, lord Lucifer! I was a poor butcher. I trawled through the countryside until I found a sick sow. I carried it on my back and took it to the butcher’s shop. I swore on my honour that it was a healthy pig.

Sixth Soul: Have mercy, lord Lucifer! I was a poor tailor and I stole pieces of fabric: green and red ones, black and white ones. Because of this I am sent to Hell.

Seventh Soul: Have mercy, lord Lucifer! I was a seducer: I embraced girls for a penny, women for a bread.

Lucifer: Satan, dear companion, do not bring him into Hell! If he comes into my Hell, we will all be made step-children!

Then Satan leads the souls into Hell.

The Merging of the Past and the Present in Das Innsbrucker Osterspiel

A short essay by Alex Peplow (DPhil student in Medieval History, who played the part of Jesus)

Das Innsbrucker Osterspiel, like many of the plays in this cycle, though primarily narrating an episode in the divine history of the world nonetheless frequently leaves its Biblical setting to introduce contemporary elements. The whole play, of course, is not intended to be scrupulously historical; the focus of the play is not on constructing first-century Roman Judea, but in realising the story of the Resurrection. This lack of attention to historical detail is taken much further, though, in the parade of the damned in Hell presented in the section performed, as well as in a lengthy merchant scene which follows it, where the pretence of a historical setting is all but abandoned. These scenes are generally comic, yet serve also as a comment on both the society at the time of composition, and an important demonstration of the continued effects of the events being presented.

The collection of the damned souls is striking in comparison with what immediately precedes it: the Harrowing of Hell, and illustrates the didactic theme of this blurring of time. The scene, with its stereotypical depictions of common occupations, is comic, yet its events are entirely serious, illustrating the practical consequences of redemption and damnation. By juxtaposing the release of souls already in Hell with the arrival of more, the play highlights the ambiguity of the result of Christ’s sacrifice. The Harrowing of Hell invokes the grant of grace in redeeming some of the dead, but this is immediately followed by the stark warning, exemplified in the soul who tries and fails to escape, that damnation is destined to be a reality for some. The play links this directly to individual sin, which is presented as ubiquitous in society. Lucifer numbers a long list (ll. 388-451) of recognisable occupations, from ‘babest vnd den kardenal’ (‘pope and cardinals’) to ‘den fischer’ (‘the fisherman’), with ‘trenker’ (‘drunks’) and ‘die klappermynnen’ (‘gossip-lovers’), as well as ‘aller ley spilman’ – ‘all entertainers’. This recitation creates the effect of levelling all people from emperor to cobbler, not in death, as in the danses macabres of fiftenneth-century churchyards, but rather in sin. The seven souls who go into Hell are representative of the whole, but they should not, perhaps, be thought of as dead. Lucifer’s actions take place in the past, yet the figures live, and die, in what is, from the perspective of the play, the future, and, from the perspective of the audience, the present. Sin, then, is presented as a force which remains in society across time, unaffected by the Resurrection. Moreover, it is not a passive entity: Lucifer’s speech is peppered with orders to ‘brenge mir’ (‘bring to me’) the various sinners, indicating an active gathering of them while in the world – the corruption of people, something which is directed from the past, from the setting of the play, but taking effect throughout the present day. In this, the mixing of the two time-frames of the play shows sin, and the Devil, as a constant, and powerful, force in the world. Lucifer’s orders in the aftermath of the Resurrection will still be being carried out many centuries later, with no diminution of their effect. Thus, although the play shows the power of the Resurrection to effect the redemption of souls, it also shows the necessity of continuously guarding oneself against sin.

The merging of the present and the past in the parade of sinners is not only to demonstrate the cosmic drama of redemption and damnation, but also for more quotidian social commentary. The figures listed, as well as those souls who then appear, are readily recognisable to the audience; they represent common complaints of medieval society. Christ may have saved sinners at his resurrection, but there still remain people who sin, and they are very easily identified and caricatured. Each sinner portrayed is explicitly associated with their occupation, as are their particular sins. Each sin is directly related to the figure causing some kind of fraud in relation to their job: the baker adds to his dough with ‘eynen cloz’ (‘a clod’), the cobbler makes bad soles, and the priest is lecherous. This relates, perhaps, to a strict idea of how people in particular roles should behave, thus treating (seemingly minor) social transgressions as equivalent to sins – as transgressions against God. Lucifer’s list of jobs also often associates people with particular pieces of equipment: ‘den becken mit dem wecke’ (‘the baker with the roll’) or ‘den salczman mit der mesten’ (‘the salt-carrier with the measure’). This creates a method of easily impersonating – or even using the real town figures – people who, in some way, had power in the town: to rail against the short measures of the innkeeper, or the high prices of the butcher or baker. In this, the anachronistic section of the play perhaps acted as a form of social relief, in which objections to the civic order, even if only on a very small scale, could be expressed harmlessly. The imagining of the crooked trader being punished for their behaviour may have provided a spur to reform for some, but, more likely, was merely a way of voicing general complaints, and gaining satisfaction from their symbolic avenging. For this reason, it is to be thought of as a method of social complaint, not control, for those mocked are socially higher up, or at least equal, with the audience, which they may even have been part of.

The moments of the mixing of the present and the past serve to emphasise that what is being depicted in the play remains relevant to those watching the play: the Resurrection was an event in the past, but one which has a continual effect on the life of a Christian. There is also, however, comedy, and irreverence, in these moments, relating to both present-day figures, as well as figures in the Biblical narrative, and it is entirely possible to hold both this and a serious message at the same time. The scene with the Devil serves two purposes, one social and one spiritual; the social was comic in its satire, the spiritual, in the fear of Hell, not. The two, however, were not mutually exclusive: the universality of sin could be acknowledged, but also laughed at. These elements in the play can be thought of as communal, binding the audience into a single unit, from which it can either express social grievances, or be prepared for moral teaching in a later scene. Above all, though, the mixture of the present and the past is to bring the audience into closer contact with the events on stage, and to emphasise that the story of the Resurrection told in the play was one which remained present in the lives of those watching.

Watch Performance

To watch all the performances please visit the YouTube playlist by clicking the link below.

About the Music

View the score here, written by Dr Andrew Cusworth, who discusses his composition below.

Like so many broadly creative things, this setting of the ‘Tollite portas’ text arose from an informal conversation over coffee – on this occasion at a coffee morning that for scholars takes place each week at the Bodleian Libraries’ Centre for the Study of the Book, during which Henrike Lähnemann invited me to write a piece for the Oxford Medieval Mystery Cycle. In subsequent conversations, we discussed the approximate parameters for the piece: the ‘Tollite portas’ text, its context in the play, the context of the performance and the needs of the choir, all of which would be critical in the process of writing the piece. Concurrently, I perused existing settings of the text, best known to present-day audiences from its appearance in Handel’s ‘Messiah’ (‘Lift up your heads, O ye gates’).

From all of this, I made a list of aims for the composition, seeking to write something:

- simple enough to be sung with relatively little rehearsal;

- that reflected the text;

- that would add dramatic impact in the context of the play;

- that allowed a certain amount of leeway in terms of time for movement and so on.

Beyond these immediate concerns, I felt that whatever I produced should be recognisably contemporary, suitable for use in other contexts; I also thought that it would be fun to make (optional) use of the natural trumpet used ceremonially at St Edmund Hall.

As obvious as it may seem, when setting a text, my work begins with that text. Setting text is, almost without exception, a complex process. The possible meanings of the text, the addition of new elements of meaning by music, and the merging of these with interpretation by performers and audience alike are fascinating and almost infinitely variable things; working with an older text adds to these things a sense of reimagination for a new time.

In this instance, the text is a Latin excerpt appearing in the dramatisation of the Harrowing of Hell from the Insbrucker Osterspiel. The Harrowing of Hell is the richly suggestive name given to the story of Christ’s post-crucifixion descent into and ascent from Hell. The traditions associated with this fable reach some way beyond current scriptural or doctrinal positions, with the word ‘harrowing’ itself calling up images both of the triumphant battle through which the souls imprisoned in Hell were released and of the shattering nature of such a thing. The majority of the text is a Latin rendering of Psalm 24.7-8, which appears in the Authorised Version of the Bible as ‘Lift up your heads, O ye gates; and be ye lift up, ye everlasting doors; and the King of glory shall come in. Who is this King of glory? The Lord strong and mighty, the Lord mighty in battle.’ In the play, these lines are sung by the angels, with Satan asking ‘Who is this King of glory?’, something that is reflected in the writing of the piece through the use of a bass soloist.

After some time for consideration, I began to piece together a sketch that I felt satisfied the needs of this text and the performance requirements. Its rhythmic motif was energetic, warlike even, which seemed apt to the imagery of angels descending against the gates of Hell. Additionally, the repeated notes, step-wise motion and limited palette make it fairly approachable for singers without sacrificing the occasional harmonic twist, and the repetitive nature of the motif lends itself to short repeatable passages if the piece needs to be extended in procession or dramatic movement.

As well as the ‘Tollite Portas’, the angels sing at two other points. In one instance, they sing ‘Venite, benedicti patris mei’ (‘Come, ye blessed of my Father’), a segment from of Matthew 25.34, which continues ‘Come ye blessed of my Father, inherit the kingdom prepared for you from the foundation of the world.’ This invocation to the souls trapped in Hell is given a softer, more seductive but no less determined treatment that reconfigures the melodic and harmonic material of the rest of the piece. The other angelic intervention in the play is the silencing of Satan, ‘Silete’; here the angels command with the same melody as used for their imperative ‘tollite.’

And this was, in a very real sense, the point from which this piece grew – the casting the angels in their more militant light. The figure of the imperious, commanding angel is one that is easily neglected against the backdrop of cherubic imagery: even Michael in his casting down of the dragon is often presented as radiantly beautiful and almost at ease in his work. In this setting, the angels are made, I hope, a little more terrible.

The piece is also available at andrewcusworth.com/scores/tolliteportas.pdf. It is free to use and licenced under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International (CC BY-SA 4.0) Licence.

Performance Locations

Hover over a location marker for performance times and links to additional information.