I Guess the Rains Down in Africa

21 May 2019|Callum Munday

- Research

Toto’s 1982 banger “Africa” has an interesting backstory. Before reaching discotheques and the CD collections of middle-aged men around the world, it was written in response to the prolonged West African drought of the 60s and 70s. David Paiche, singer/songwriter, had watched a documentary about the drought and with inspiration from his Catholic upbringing, wrote the now famous line ‘I bless the rains down in Africa’. He had never actually been to Africa himself.1 If he had, he might have been inspired instead to become a climate scientist.

At the time of the droughts, the proposed causes were fiercely debated. Climate scientists had two contesting theories. In one theory, deforestation and cropland expansion set off a chain of atmospheric processes which ultimately lead to reduced rainfall. In this version, humans — and particularly those living in West Africa — were to blame for the drought. In the second theory, the drought was caused by anomalies in the temperature of the global oceans. These anomalies affected the summer monsoon by reducing the supply of water vapour to West Africa. In this version, the blame lay with the vagaries of the global oceans, out of reach of human control.

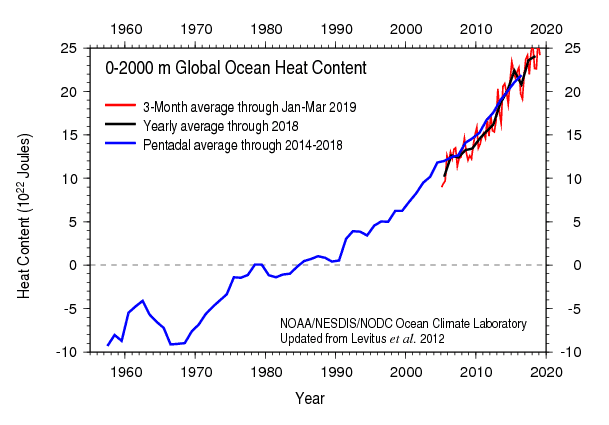

We now know that this latter theory is most likely the root cause for the drought, but we are increasingly aware that the whims of the global oceans are not outside of our sphere of influence. The release of carbon dioxide into the atmosphere at unprecedented rates is warming the planet. Every second, one atomic bomb’s worth of extra heat energy is being absorbed by the oceans, and the warming of oceans has the potential to alter the pattern and magnitude of rainfall on a global scale.

Of particular concern is how this warming will influence the frequency and magnitudes of drought. The climate models we rely on to make these predictions do not always agree with one another. For example, about half the climate models used by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change suggest global warming will lead to drying in West Africa, while the other half suggests it will get wetter. Such uncertainty leaves policy makers with the unenviable task of preparing for a wide range of possible futures. It also presents a pressing challenge for climate scientists: can we work out, ahead of time, which of these futures is most likely?

One approach to answering this question is to evaluate the climate models used to make predictions. We tend to have more confidence in models which do a good job in simulating the present day state of the climate system compared to the models which do a bad job. This is obvious.

What is less obvious is that the present day state of the climate does not always affect how the climate will change in the future. Therefore, to rule out projections of future change, we must show that the model errors which in simulating the contemporary climate system will matter for how they simulate the future change. For example, do models which are too wet compared to historical observations project more wetting in the future?

Work along this line of investigation is in its infancy, but early results are promising. In southern Africa, we have recently found that the most extreme drying trends are only found in climate models which contain large errors in how they simulate the present state of the climate system. This suggests that in Southern Africa, while the warming oceans may cause drying, they might not cause extreme drying. Hopefully this information can be used by policy makers faced with decisions about how to allocate resources in response to a changing climate.

Apparently, Africa by Toto is now being played on loop through solar-powered speakers in an unknown location in the Namibian Desert. Whether anyone will ever find those speakers is up for debate, but the need to guess the rains down in Africa is not.

1 On the topic of Africa-inspired chart-toppers, the Yuletide ditty ‘Do they know it’s Christmas?’ by Live Aid and its derivations, in addition to being reasonably condescending to an entire continent of diverse peoples, it falsely states that ‘There won’t be snow in Africa this Christmas time’. In fact, snow can occur at the peak of Kilimanjaro year round, especially in December, and South Africa even has its own ski resort in the Drakensburg Mountains.

Read more on our blog

Category: Research

Author

Callum

Munday

Callum is a Fellow by Special Election in Geography at St Edmund Hall and is a climate scientist specialising in African climate and climate change. He is currently working on a NERC- funded project in southern Africa and is a visiting scientist at the UK Met Office.